Armless fun: The rise, fall and rise of the ‘jumper over shoulders’ look

Shouldering the load

Words: Joseph Bullmore

In certain pockets of Southern Spain, northern Italy and western France, there exist entire generations of men with no idea that their sweatshirts have neck holes. You know the sort. Handy at pétanque. Belly like a yachting buoy. Lacoste polo tan-line on the torso. Never seen a sock. Up and down promenades and boardwalks they stroll, deep in debate or silence, two by two, as if Noah’s ark was sponsored by Vilebrequin. And there, on their shoulders, its arms flapping like a Parisian poet’s scarf or loosely knotted like a teenage engagement, lies a jumper in cashmere or wool or both, positioned as if it has fallen from a cloud or a passing Gulfstream. It is deliberately un-deliberate. A shrug in natural fibres. Worn in precisely the right way, the garment becomes a symbol of its own redundancy. The best way to telegraph that you live somewhere that is too lovely to require jumpers is not to not wear a jumper — it’s to wear a jumper only slightly.

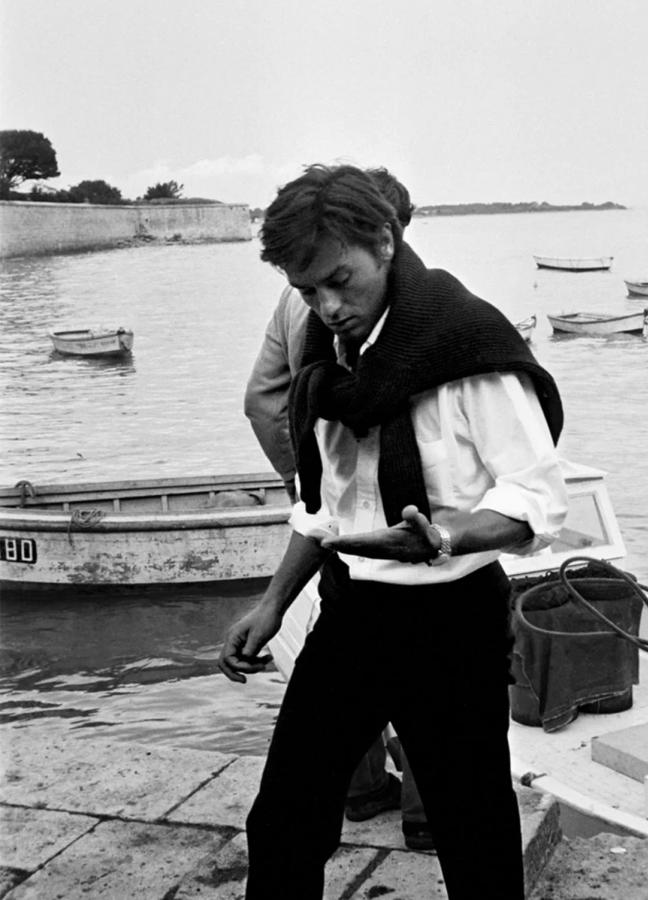

Style icon Alain Delon wearing a jumper on his shoulders is perfectly in keeping with his effortlessly cool Riviera aesthetic

This, I think, is one of the reasons that the whole ‘jumper over shoulders’ (JOS) look is having a ‘moment’, and one that’s felt far away from Cap Ferret or Sotogrande. You see it on Drake’s models and Ralph Lauren shoots and Aimé Leon Dore moodboards now more often than you don’t — which means it’s coming for Mango Man and Zara and your little brother tomorrow. It is a cornerstone of the new wave of urban-prep, like tennis caps with suits or Olympus Mjus as necklaces. It signals a continental loucheness, an old-money unfussiness, a sunkissed dolce far niente — each of which is otherwise famously hard to come by if you’re a stressed out mid-level creative director in Battersea. It always falls on its feet, like a Loro Piana cat. It is late-season Cousin Greg on a yacht. It’s cooly, calmly, almost cockily aspirational, although it would hate that word. And it is what it is thanks to more than a century of status anxiety and studied casualness combined.

Things start, in the cultural memory, with Brideshead Revisited, and punts and cricket jumpers and teddy bears and Pimm’s. JOS, in this context, is effete, affected, louche. To some on campus, it is a coded ‘lifestyle’ garment; a signal of ‘confirmed bachelorhood’ and other things. But to many it is simply a sporting, jocky staple, and mostly one of monied, careless privilege. From here, things jump across the Atlantic (but not too far across) to the East Coast Ivy League in the late 1950s and early 1960s — the era that Take Ivy, the endlessly moodboarded Japanese coffee-table book, immortalised in its pages. A little later, JOS becomes a standard WASP calling card, a signature of doughy, pink-cheeked prep culture, like madras shorts or LL Bean bags — ideally moth-eaten, inherited, ancient. Moments later, it appears on the backs of new-money New Yorkers, too — specifically the Greed is Good graduates of Wall Street — as a weekend version of the two-tone shirt and red braces. Then, as we approach the end of history in the 1990s and beyond, everything becomes compressed and meta and ironic: JOS a shifting symbol used by J Press, Ralph Lauren, J Crew, Abercrombie, Tommy Hilfiger, Jack Wills, Hollister, et al, et al, on and on, with varying degrees of referentialism, faux nostalgia and imported class anxiety (Carlton Banks was a big perpetrator in the cultural consciousness here).

For a while, and until fairly recently, this tired, posh-adjacent association rendered it distinctly, famously uncool — a frumpy cousin of red trousers, gaucho belts and signet rings (Urban Dictionary minted the phrase ‘sweaterdouche’ in 2010 to describe the look). In many ways, JOS was the sleeve-heavy relative of the sleeve-less gilet, and its swift rehabilitation (remember when even attempting the soft ‘g’ on gilet made you a subject of derision?) has been just as remarkable.

Aleks Cvetkovic, the style writer and HTSI regular, smells a Nordic influence at play here — the cleansing air of mid-century, Swedish understatement. “Chic Scandi brands like Saman Amel, Rubato and Berg & Berg are all into it now, and I’d look to these as great examples of how to wear the look well,” he says. “They tend to layer jumpers over other lightweight knits, or over unstructured tailoring rather than baggy shirts or trad jackets. This helps the look to feel contemporary and understated rather than affected.”

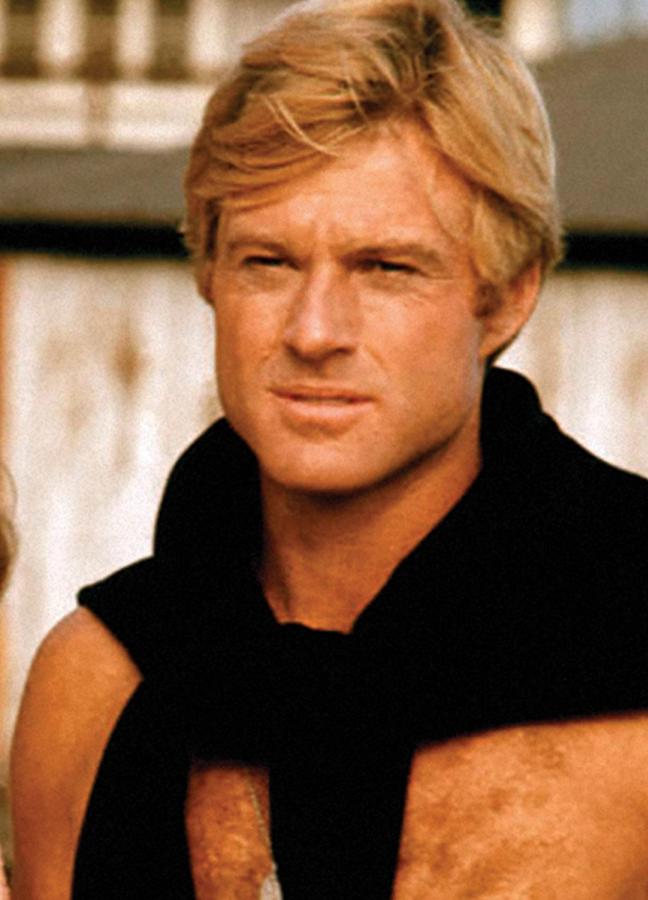

A shirtless Robert Redford sports the jumper over shoulders look on the set of The Way We Were, Los Angeles, 1972

Konrad Kay — the co-creator of Industry, a programme that cares deeply about the clothes its banker characters wear and what they mean — says the JOS renaissance is partly down to Aimé Leon Dore’s current vogue. “Whether you like the brand or not, ALD’s lookbooks are super influential — downtown meeting uptown”. Now, he says, the snootiness of the original look has been softened by the edge and egalitarianism of streetwear; of ALD’s Queens upbringing, for example. “Now when I see someone deliberately doing jumper over shoulders, I think it’s more a signifier that he’s into #menswear than a class signifier.” As much as anything else, he says, “now it makes me think of Tyler, the Creator.”

Isaac Marley Morgan, Head of Art Direction at Drake’s, detects a similar high-low sensibility at play, and adds that maybe JOS can be worn playfully precisely because it’s historically so played out. “I feel there’s a slightly tongue-in-cheek way I wear suits,” he says. “Sport socks with loafers, for example, or a cap. And I think throwing a jumper around my shoulders is an extension of that. It’s an upward-facing posh thing to do for a working class lad from Ipswich.” Finlay Renwick, the Editor at Drake’s, agrees that JOS is certainly less class-anxious than it was 20 years ago. “I’ve seen guys in New York, London, Venice and the English countryside all riffing on the look in their own way. Trends have been compressed,” he says. “Your clothes don’t necessarily represent who you actually are.”

“There’s also an irony to it,” he continues. “You might be winking at the idea of dressing like a Slim Aarons photo.” Ah yes, Slim Aarons. Aren’t these things somehow connected? For most of the second half of the 20th century, Aarons’ society photographs weren’t particularly fashionable. In fact, they were often seen — with their gaudy pedestalling of the wealthy, their sunny primary colours and their distinct lack of edge or danger — as slightly dowdy, a bit too establishment, certainly lacking the candour and grit of reportage photographers or fashion snappers. It was one of Getty Images’ finest deals buying Aarons’ entire back catalogue off him just before he died in 2006. They will have returned their investment thousands of times over, such is his sudden modern vogue.

Now, the same images that looked safe or staged or too symmetrical appear wholesome, nostalgic, poignantly evocative of a lost time and pomp. Wes Anderson does something similar on screen. Ralph Lauren has always kept a certain world uncannily alive. Loro Piana’s Succession-tinged supremacy is entirely linked, too.

These things, just like jumpers over shoulders, allow us to daydream momentarily that we do not live when and how we do; that we do not have email anxiety, doubling mortgage rates, vitamin D deficiencies. We hanker for the simple snobbiness of 1980s prepdom, or the jaunty croquet of Brideshead. It is cosplay for the soul, without (much of) the ridicule.

Renwick sums it up rather colourfully. “I sometimes quite like the idea of role-playing as a sexy Italian man if I find myself in Rome or Florence,” he says. “Three buttons undone on the Brunello linen shirt, a jumper draped freely across my shoulders. Why not.” And then: “Quickly it dawns on me that I’m actually not a sexy Italian man. I’m from Sussex. Life is so unfair sometimes.”

This feature was taken from Gentleman’s Journal’s Summer 2023 issue. Read more about it here…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.