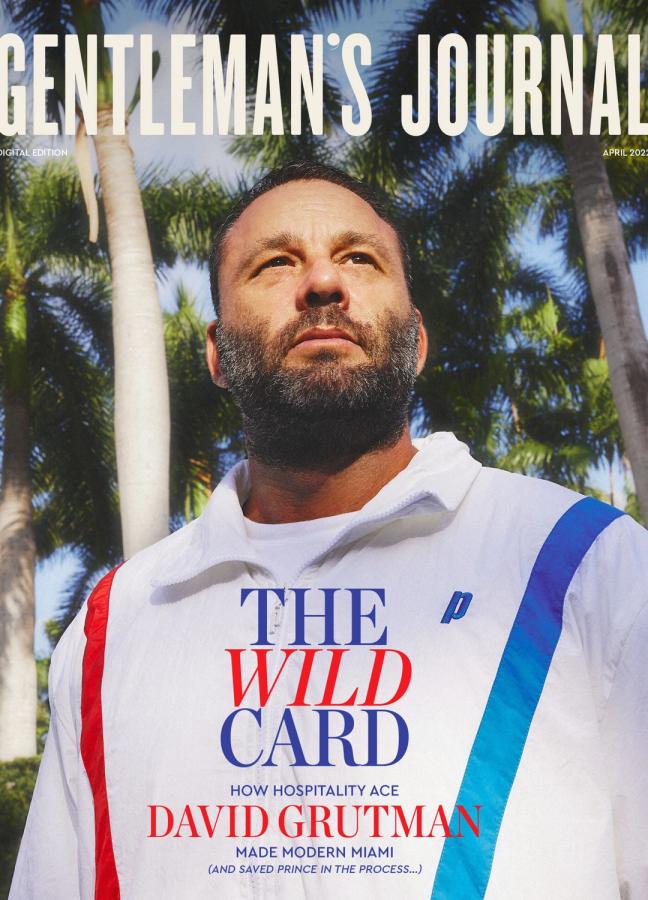

The Wild Card: How hospitality ace David Grutman made modern Miami

He's the city’s favourite son and its big brother, and the man behind Miami's most legendary venues. Oh — and he's just ingeniously revamped Prince, the once-ailing tennis brand that he saved from bankruptcy. But David Grutman is just getting started...

Words: Joseph Bullmore

Photography: Mario Alzate

The lads on the flight have been singing for seven hours. They’re from Liverpool, and, like geiger counters tuned to Scouse, have quickly identified everyone on the entire Virgin 9750 flight who is also from Liverpool, or who has a great-grandmother from Liverpool, or who has recently visited Liverpool, or who has ever visited Liverpool, or who has ever heard of Liverpool, or, a little later on, who has ever heard of absolutely anything at all.

We can all hear them, of course — and what we hear, about as regularly as the air hostesses will bring around the mini Kahluas, is the memorable opening bars of Will Smith’s ‘Miami’, that impossibly nineties hit which was, until The Slap, the man’s most enduring contribution to pop culture. This is the boys’ third attempt at this trip to the Floridian hotspot, their other two having been scuppered by Covid. They drove down from Liverpool at 3am that morning to make the flight, and have no intention of sleeping now, later, or at any point, really, in their four-day jaunt. (I like them a lot, and they make the officer at the Department of Homeland Security laugh as they sway through the border, which I have never seen anyone do before.) They’re down for Spring Break, of course — that fluorescent ritual in which the college kids of America fly like migrating birds to Miami’s South Beach in a riot of sunburn, imported house music and hard seltzer. And they think they’re here because of Will Smith. “Party in the city where the heat is on, all night, on the beach till the break of dawn.” That sort of thing. But what they don’t know yet — and what they might never know, perhaps — is that they’re really here because of David Grutman.

David Grutman is sometimes called the King of Miami, though he doesn’t particularly love that label. (For one thing, royals tend to inherit their standing, whereas Grutman worked tirelessly for his. For another, it paints something of a target on his back, I suspect). But it is helpful, at least, in conveying to a British reader the unique sense of loyalty and adulation he enjoys in this neck of the woods, where small crowds gather and coo if you attempt to shoot his portrait out on the street. And it helps to explain, too, the industry and imagery that has been built on his back. England has the Queen: afternoon tea, Buckingham Palace, stiff upper lip, corgis. And Miami has David Grutman: swaying palms, famous faces, beautiful people, and good times above all else. Grutman didn’t put Miami on the map, of course — but he did make the map look more beautiful, more enticing, more shimmering, more Miami. His empire, Groot Hospitality, spans two gigantic clubs (the iconic LIV and Story), six restaurants and one hotel in the city alone. But, once you’re here, it feels bigger than simply the buildings themselves. Yes, the Beckhams and the Kardashians know and love Grutman. But so do the taxi drivers I speak to, and the kids playing soccer in Flamingo Park, and the guy selling tacos round the corner. In this way, you could call him the unofficial Mayor of Miami, I suppose — but that might be tricky for the actual Mayor, who he is friends with, of course, and who messages Grutman several times on the day we meet. Well, him and just about everybody else.

This is my most abiding memory of David Grutman — the pinging of the phone. You have never heard anything like it. It punctuates his sentences like exclamation marks. Pharrell Williams, with whom Grutman owns the Goodtime Hotel in Miami, checking in on this or that. Noah Tepperberg, the hospitality honcho behind TAO in New York and now Hakkasan everywhere, asking for advice on something or other. An American football star sending him a link to “someone I find interesting.” Cody, his co-owner at Prince, the once-ailing tennis brand of which Grutman is now also creative director, asking about a table somewhere tonight. An advisor checking in on a potential real estate deal for a vast new resort; all big money and hush-hugh. The phone is almost steaming; it looks hot to the touch. Ping. Ping. Can I call you back. Ping. Ping. Not now. Ping ping ping. I’m doing an interview. Ping. And that’s without the rolling bombardment of calls and voice notes and DMs — or the steady cascade of Instagram stories which Grutman uses to document the particulars of his very colourful days.

These usually begin sometime around 6am, while Grutman’s competitors are busy snoozing off the Don Julio, and when the sun above Miami still has the dimmer switch turned down low. At 8am, five days a week, Grutman is out on the tennis court — usually the private one he hires down on Sunset Island, a chi-chi gated neighbourhood to the north — hitting balls with Jimmy Bollettieri, his rakish, walnutty master coach, or whoever in the rolodex is available.

"It's funny how these famous people get nervous suddenly..."

On the day we meet, Grutman is hitting with Genie Bouchard, the former top five-ranking pro, who seems thoroughly amused to be there. At one point, as she approaches the net, Grutman plants a stonker of a forehand right on her bicep. (“Did you see that? I nearly killed her!” he says later with a devilish smile.) On any given weekday, though, it might be Danil Medvedev, or Juan Martin del Portro, or simply ‘Serena’. At first, he had to invite the pros along. But now they ask to come, specifically and personally. They want to hit with Grutman, of course — but they also like the idea of appearing in his ‘Life Lesson’ Instagram stories, in which the man and his playing partners share pithy mantras with his 800,000 followers every morning. “[He does] these short words of advice and affirmations,” says Joe Jonas of the daily videos. “I love it. It really inspires me to go out there and crush it and to enjoy life to the fullest, which he does so well.”

I ask Grutman how these videos came about, once we get back to his apartment in the Zaha Hadid skyscraper that towers above Midtown — a sort of alien chrysalis with valet parking. In the weird way that algorithms and culture can conspire, these little snippets are, to many people who have never set foot on Miami beach, what Grutman is best known for.

“I started playing tennis almost two years ago, and usually we’re with fun people,” he begins. “So I thought it was a fun way to end it, to get someone’s life lesson. I always like to hear someone’s go-to words of advice. But even better is that there are always a lot of bloopers. People mess it up. It’s so funny that these famous people get nervous suddenly.”

Grutman is sitting at one end of the table, still in his tennis gear: a portfolio of his greatest hits with Prince — all 1980s pomp and playfulness, as if Bjorn Borg had let his hair down a bit. In the open-plan kitchen-dining-room-art-gallery we’re sitting in, it’s hard to know where home begins and the office ends. Max, Grutman’s unflappable chief of staff, hovers industriously with multiple phones. A chef is cooking something exotic and fragrant on the kitchen island. Sophie, Grutman’s head of marketing, sits at the end of the oval table, listening and cajoling. But Grutman’s two young daughters are here as well, playing with the cat and apparently utterly unperturbed by the photographers stepping nimbly around them, trying not to get marks on the marble floors. And Isabela, Grutman’s wife, floats in and out of the room, too, and pretends, very sweetly, to have heard of our magazine.

Does Grutman have a mantra himself? “I always say ‘take it personally’ — care about everything,” he says. “Why is that person eating somewhere else? Why is that person partying somewhere else? You should be offended.

“I’m fully offended when somebody comes here and they don’t eat at one of my places. I take it really bad. Milos has an open window — an amazing restaurant. Normally you wouldn’t fault someone for going to Milos. But it’s right next to Papi Steak. And if I see one of my friends eating there, I go like this — I take my finger and I cut my neck. And now everyone knows not to sit by the window…”

A little later on, Grutman explains how “loyalty is a huge trait for me. One of my things is that, if I have a great relationship, I stay with the people through the ups and the downs. If you’re only with people when they’re up, that’s not actually a relationship.”

It’s trite nowadays for companies to refer to themselves as families, mostly because it’s almost always patently untrue. But Grutman’s orbit has a certain fraternal energy, for sure — perhaps because David is like some archetypal big brother. He teases and coaxes. He’s competitive and playful. I suspect he’s handy with a practical joke. He gets a certain devilish look in his eye whenever he offers you something — an acai bowl, a hard seltzer, a flight to Vegas, perhaps — which dares you to say yes, and so you usually do. When he hires people, he tells them he wants them to be their own bosses one day — even if it means that they eventually fly the nest. He was an only child growing up, he tells me — and you begin to feel, when you look at his huge array of friends and colleagues and business partners (many famous, many not) that he has been acquiring surrogate brothers and sisters ever since.

“David loves his immediate family, but also his extended family — the friends he calls family,” explains Jonas. “[When we first met], he took me under his wing, and showed me around [Miami], and I just felt so welcome.”

Kendall Jenner agrees. “He has known me since I was just a kid, and will always be like a big brother to me,” she says. “He is special, charismatic, loving, and the absolute funniest. In an industry that can make me uncomfortable at times, Dave makes me feel safe.”

Grutman’s parents divorced at six. “I was left alone a lot,” he tells me. “I’ve had many years of therapy, and I’ve realised that I might have grown up feeling that I was insignificant, and that drives a lot of what I do. I’m running away from being insignificant. But I’m not so insignificant any more…”

"If you’re only with people when they’re up, that’s not actually a relationship...”

Grutman was born in Naples, on the Western edge of the Florida peninsula — a pretty but sleepy retirement hotspot. He moved to Miami after getting a degree in finance from the University of Florida. “My first job was bartending at a bar in the mall. It was amazing — it was the best year of my life. I said I’d just do it for a year, and then I’d move back to Naples. But I just got so passionate about it.” From here, he worked his way up every rung of this notoriously slippery ladder — working a lifetime for his overnight success, as the old joke goes.

“It wasn’t like I came here and had a rich father who said: ‘here, go buy a restaurant’. I took the time to learn all the jobs, because I had to. And that really gives me a leg up with the competition. A lot of people think they can come in and work it out. But in this business, when you lose — you lose big. And that happens against me a lot…”

In this industry, in this town, it’s not just what you know, of course — it’s who you know, too. Or, more precisely: it’s what you know about who you know. Grutman’s genius was in leveraging influencers long before we called them influencers — using his natural network of friends-in-high-places to create hype and intrigue around his openings and sites. “At the end of the day, building a brand is building a brand. I do it through celebrities. I do it through partnering with other brands to use their marketing power. And I do through influence,” he says. Which is a bit like a magician showing you his box of tricks — but none of the sleight of hand, Jedi-mind techniques, or decades of practice that go into pulling them off. With the Goodtime hotel in Miami, for example, Grutman didn’t just use Pharrell Williams’ name, or face, or social clout: he brought him in and had him plan things from the ground up. “I always tell people I’m partners with the Dalai Lama,” Grutman says of Williams. “He’s just about doing good. He loves ‘goodwill, goodwill, goodwill,’ and his whole thought process is that goodwill comes back to you tenfold — which is a fact. He’s a genius. He sees things way ahead.”

Nevertheless, hospitality is perhaps the most brutal industry known to modern man. In Miami, as in London, restaurants and bars come and go like fireworks: huge expense, great expectation, pretty crowd, big bang — and then a fizzle back to the ground in darkness and silence. Sign painters are the only consistent winners in this game — knowing that every new fixture they fit will likely be replaced by something newer and shinier in 18 months, once the owners have had a minor mental breakdown and hot-footed it out of town. To have one successful restaurant or club is a triumph; an odds-beating anomaly; a freak. To have seven is ridiculous — it’s to be the Warren Buffet of steaks. Grutman is a plate spinner extraordinaire, with a string of hits to his name. “I love the chaos,” he says. “That’s the fun part for me. The newness. The excitement. Taking a raw space, and creating an environment that people want to go to again and again. That’s what I do.”

Not that there haven’t been failures. “When I opened my first nightclub, everything I did was to show the last nightclub that I worked at that they should have made me an owner,” Grutman says. “And I failed miserably. I threw the kitchen sink at it. And I failed so miserably that the original company bought the club from me.” He winces. “Oof. Painful, man.”

Now, however, the numbers speak for themselves. “LIV [the mega club Grutman owns at the Fontainebleau Hotel] might do $65 million this year. That’s a real asset.” Then there’s Papi Steak, the extravagant dining spot where diners sometimes get their steaks served in glowing, Pulp Fiction-esque briefcases. Per square foot, it is the most profitable restaurant in North America. Forget Manhattan or Beverly Hills. Pound for pound, this is the most lucrative dining spot in the entire country.

"I failed so miserably that the original company bought the club from me..."

All this is underwritten by a formidable, towering work ethic. Even the bits that look like play — when Grutman might drop into one of his own clubs or a rival restaurant; when he’s hitting with an A-lister on some hazy Friday morning — are part of the job. “It’s painful for me to eat in other places,” he says, “because I see stuff that’s wrong and I want to fix it, but I don’t want to be disrespectful. But eating dinner with me at my own places is tough, too, because I’m looking around like crazy. The servers are used to it now — but even the top servers choke with me. They just choke. They write it down, but they miss something, or this goes wrong, or this happens — but at this point I just know to say that it is what it is.”

Grutman has also realised that people don’t really follow brands — they follow people. “I try to create a lifestyle around myself. A lifestyle that people buy into. It’s more authentic that people know the real me.” Which is why the co-acquisition of Prince, the wounded titan of seventies and eighties tennis that had ended up filing for bankruptcy, is so canny. He is not bringing a background in tennis or in fashion or in performance-wear to the creative director chair. He is bringing a mood; a sense of play. “I’m in the fun business,” he says at one point during our chat. Too often, style brands forget that they should be, too.

“Prince is a beautiful brand. But I said: “I’ve got to do it my way. And now I’ve brought it back to my kind of crew. I’ve done it through collabs with friends of mine. I love the heritage and how iconic it is. I love vintage t-shirts, I love retro and that style and feel — it resonates.” When I google the brand, I notice it has just released a collaboration with the nineties athleisure tastemakers Sporty & Rich — the pinnacle of the new referential, preppy, post-divorce-Princess-Diana aesthetic. That sort of thing, to borrow a Grutman watchword, resonates.

So, what’s next?“I’ve never done a project with David Beckham, but it’s going to happen at some point,” Grutman says. “This guy loves his food better than anyone I’ve ever met in my life — and he knows his wine better than every one of my sommeliers. It’s kind of impressive. And if he doesn’t do something, it would be a shame, because I think he has a real mind for it. If he wasn’t a pro soccer player and soccer team owner, I think he’d be great in the hospitality business.”

But it is a tough business. An all-consuming game. Your phone will ping at all hours. You will need to show your face at a nightclub at 4am, and then play tennis at 8am for a men’s lifestyle magazine shoot. Your friends will be your business partners, and your business partners will be your friends. As we wrap up, one of Grutman’s daughters sits on his knee. Does he work any less hard now that he has kids, I ask? “I don’t take more time off, no. But I want to make sure that in the time I do have with them I’m present,” he says. “Which I have a real issue with. Because I’m all over the place in my head, and to be present with them is important,” he says finally. “But I want them to have a good life. So I have to work hard.” The genius of David Grutman, perhaps, is that he makes even the hard work look like play.

Read next: At home with Jean Pigozzi — tech investor, art collector, and the world’s best connected man