The billion dollar loser: The rise and fall of WeWork

Tequila shots, private jets, super powers and baby rompers — the rise and fall of Adam Neumann and WeWork

- Words: Gentleman's Journal

- Words by : Joseph Bullmore and Reeves Wiedeman

“A million dollars isn’t cool,” Sean Parker once said to a young Mark Zuckerberg. “You know what’s cool? A billion dollars…” How quaint! How small minded! How very 2004! How we’ve moved on. Any founder-CEO worth his salt these days knows full well that a billion dollars is nothing. You can make a billion selling tequila with an old pal. You can make a billion aged 19 flogging lipgloss to teenagers (and having a sister with a game-changing sex tape, to be fair). No — what’s really cool in this day and age is a trillion dollars. And, just for a moment, for a glimmering, glittering half second, it looked like Adam Neumann — the six-foot-five towering, office space shilling, tequila shot pitching, private jet buying, baby romper sewing, SoftBank beguiling Adam Neumann — might just be the man to make it. “My name is Adam Neumann, King of Kings. Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!”

Nothing besides remains. (Well, apart from a billion or so dollars in the back pocket — but more on that later.) Neumann — whose WeWork behemoth exploded (in the good way) before exploding (in the bad way) in the space of just 10 years — presents the ultimate cautionary tale for our age. His is a fable with free beer on tap. And there will be no better account of it than the one just laid out by Reeves Wiedeman in his book Billion Dollar Loser. This is a story that is stranger than fiction — no mind could confabulate anything quite so outlandish, quite so wild, quite so damned ambitious. Well — perhaps one.

Adam Neumann grew up on a kibbutz in Israel, where the communal ethos inspired him and disgusted him all at once. He liked the idea of community and fairness; but he liked even more the idea of making a huge amount of money, and rising far above his peers. The two didn’t get along in his sleepy commune — but it was possible that they might in New York, where Neumann landed in his early twenties. Here, the chance to change the world for better (or at least forever) could exist side by side with the opportunity to make gargantuan sums of cash. Neumann tried to meld the two thoughts through various ideas — first a pitch for women’s shoes with retractable heels (which bombed); and then an idea to sew knee pads into baby romper suits and flog them to Manhattan yummy mummies. (“My generation will not accept our babies crawling on the floor with their knees hurting!” read his noble, and utterly misguided, mission statement.)

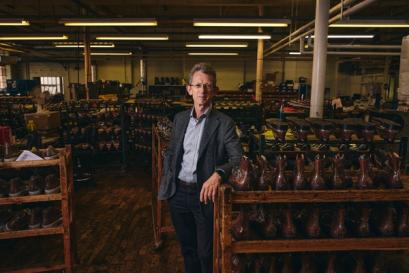

Adam Neumann in 2015. Credit: TechCrunch

But it was only when Neumann stumbled upon the idea of communal, flexible office spaces that things really started to happen. This was not a novel concept in any way — Neumann’s original ideas were not good, and his good ideas were not original. But with his unique cocktail of utter self-assurance, towering height, do-or-die attitude and messianic zeal, the entrepreneur managed to make things happen. Well, what wasn’t to like? The guy promised free beer to all renters. He did tequila shots in pitch meetings. He smoked weed at his desk. And he had visions to take over the world. Soon, out from mere office lets, a whole universe of possibilities had spawned. This, Neumann bragged to anyone who would listen (and there were a lot of people willing to listen, from JP Morgan Chase to Goldman Sachs) would be the ‘WeDecade.’ There would be schools (WeGrow); apartments (WeLive); gyms (WeWork Wellness). Even, one day, a colony on Mars (though Elon Musk had other ideas about that, as you’ll see). Anything, for a brief moment, seemed possible — especially with the investment capital cascading constantly in.

By 2017, WeWork was valued at some $20 billion, thanks, in no small part, to a large cash injection from SoftBank, the Japanese megafund. SoftBank’s founder, the enigmatic, god-like Masayoshi Son, clearly saw something in Neumann. Sadly, he didn’t see through him. To track the ins-and-outs of this intertwinement — between Son and Neumann, Softbank and WeWork — is to track the rapid rise and embarrassing fall of a cantering, braying unicorn. Wiedeman’s book charts this journey utterly brilliantly — with all the delectable details you would hope for in a truly modern morality tale. There are private jets billowing with marijuana smoke; a vanity project film starring John Lennon’s son; a hidden S&M dungeon; a kombucha-fuelled wedding from hell. In the end, after a disastrous and bizarre IPO attempt, the visionary leader limped away from the monster he had created, greatly exposed and widely mocked. One senses, however, that this is only an intermission to the story — it is not an ending. But the joy, either way, is in the telling. Adam Neumann would famously ask everyone he met what their “super power” was. Based on this, Wiedeman might answer that it’s storytelling — deliciously dry yarn-spinning. Here, the author charts his journey into a particularly modern madness. – JB

The story of Adam Neumann and WeWork is all consuming. To try to tell it, I had to talk to 200 or more people. It became fairly obsessive. But while in a pandemic-induced lockdown, I had nothing better to do than to become obsessed.

Adam is not your average Joe. He is someone who takes over a room. He is very tall, which is not an insignificant part of his story. He is very charming. He knows how to identify his audience and find out what they want to hear — and to deliver it to them. Those are pretty special skills, no matter what you’re doing. And those parts of his personality were key to his success.

I first met Adam in April of 2019. It was at WeWork’s headquarters in Chelsea, New York. We were in his office, and I noticed two things. Firstly, that he was incredibly charismatic and very confident — the type of person you want to be around. But on the other side of it — the skeptical, journalist side of things — I was thinking: this guy isn’t answering my questions. Every time I asked him something difficult, he just began saying what he wanted to say. That in itself is a skill. I think I saw through that a little bit — but I also understood why people of all kinds, from investors to employees, wanted to buy into what he was selling.

At one point, I asked Adam what his super power was. That’s a classic WeWork trope. But he instantly turned it round on me, and asked me what mine was. Eventually he did give me an answer — he said his super power was “change”. That’s probably accurate: Adam Neumann was someone who could change his personality and what he was saying depending on the situation he was in.

The WeWork story is a New York phenomenon. Adam was a person that came from somewhere else, in his case Israel. And that’s the New York story — it’s a city built by people who came from somewhere else, trying to make it big. It’s a version of Hollywood, in that way. But rather than actors, it’s all about inspiring titans of business. And as much as WeWork tried to tie itself to the Silicon Valley startup game — and as much as Adam spoke in high-minded, world-changing rhetoric — this was a real estate company. Adam was a hard-nosed, real estate dealmaker, who, behind-the-scenes, was as cut-throat as any New York landlord.

A WeWork space in Vancouver. Credit: GoToVan

It’s useful to remember the time period when WeWork was growing. It was after the financial crisis — a time when all these tech companies were growing incredibly fast. When WeWork started, Uber barely existed; AirBnB barely existed. There were all these companies disrupting various industries and becoming unicorns. What Adam did very skillfully was to go to tech investors and say to them: “look how much money I’m making. I bring in rent every month. The apps you’re trying to build spend years trying to get customers, and then they figure out how to make money. I’m making money right now.”

When he went to the more traditional investors — the banks — his pitch was that real estate was this multi-trillion dollar industry, and that he was going to change the way it worked. He told them he would capture a larger slither of the industry in a way that no-one had done before — because he did things differently. At that time, there was a belief, and a hope, that any number of companies were going to become giant unicorns. And WeWork was the one that positioned itself best as the giant of the real estate world. There was a sense from investors of not wanting to miss out. Adam is very convincing — and venture capital investors often say they invest as much in the entrepreneur as they do in the company. If there was anyone who was going to pull it off, it was someone as crazy as confident as him.

I never got to witness Adam during a pitch, but he clearly had his rehearsed lines. He would endlessly compare WeWork to Amazon. He would say that they were on a trajectory that was faster than Amazon’s. But the tequila shots were a not insignificant part of the whole process. It wasn’t like he was getting people drunk in a pitch.

Either he’ll end up in jail, or he’ll become a millionaire.

But he was someone who had a good time, and investors wanted to be a part of that. It dovetailed with what WeWork was selling — we have a beer keg; you’re going to make friends. It felt unusual, but it was something that anyone who works in an office every day wanted to get involved with. It was part of his shtick, and it was compelling, even if it made people roll their eyes.

There’s a story about Adam that takes place on the rooftop of one of his buildings. He was finalising a deal with some Chinese investors, and he brought them up to the roof of his WeLive apartment buildings in lower Manhattan. Adam told someone to bring a tray of tequila shots, and he grabbed a fire extinguisher. Everyone took a shot. And then Adam sprayed the Chinese investors with the fire extinguisher in some kind of celebratory move. It was a pretty crazy thing to do — but everybody laughed, and they signed the deal immediately.

There were plenty of investors who passed on the company. Some of them passed first time, and then came back and invested later: Fidelity, for example. There were landlords that didn’t want to lease to them. There were people that saw through the pitch. But Adam kept winning. The company kept growing bigger. He kept finding new investors. Eventually, by the end of it, even the people who were skeptical had become unsure in their skepticism. There was a sense that maybe he was going to pull it off — even if it didn’t make any sense.

At one point, Adam met with Elon Musk. Adam had talked frequently about wanting to build a WeWork on Mars. It was a somewhat jokey idea. But it was also serious. It was part of this whole notion, which a lot of startups have now, of constantly shooting for the next thing. It’s a way to drive your company constantly forward. But when Adam met with Musk at SpaceX HQ in Los Angeles, it was all over pretty quickly. Elon was late. He didn’t seem particularly interested in what Adam was selling. Adam seemed to think that getting to Mars was the easy part — the hard part, he said, was figuring out how to live there. Elon didn’t think that was right — and the meeting ended almost immediately. Adam was incredibly dejected. This was a group of people he wanted to be a part of — the upper echelon of start up visionaries. And they had rejected him outright.

Credit: Ajay Suresh

Adam’s driving instructor once said: “either he’ll end up in jail, or he’ll become a millionaire.” I think Adam was always riding that line. You could say that about a lot of people — there’s always been a thin line between smart and crazy. But most of us are not inclined towards craziness. We’re too risk averse; we’re conservative. Adam never had that. From his earliest days, he wanted to go big, and was willing to do whatever it took — whether that be sneaking into a pool as a teenager and going skinny dipping, or pushing the boundaries of ethical questions at the company — to get there. He was willing to take risks. You could argue that that’s the only way to become what Adam wanted to become — the world’s first trillionaire; someone that truly mattered. The question in Adam’s story is whether that’s a worthwhile goal — and what you’re going to lose along the way.

For all his outward confidence, people who were close to Adam suggested that he was also insecure. He was proving himself, and he had been ever since his younger sister became a supermodel. He was the older brother with a failing business in baby clothes. But he had an ability, from the moment he stepped in the room, to make that insecurity disappear. It might take him a minute or two — but once he got into the groove of whatever pitch he wanted to make, he was as good at it as anyone. I guess the secret is that we’re all insecure in one way or another, and it’s how you deal with it that matters.

I have spent a lot of the last decade reporting on start ups. I wrote about Uber, about Vice Media — companies with good ideas. WeWork didn’t invent co-working, flexible offices — but people liked the offices they created. Uber didn’t invent taxis — but people liked using their taxis. The issue, however, with a lot of these companies is that their ambitions get too big. WeWork moved into apartments, and a school, and a gym. Uber didn’t want to be a taxi service — they wanted to move people and things around the world. A lot of the problems that emerge from these companies — whether in their business models or their culture — come from two things: growing too fast; and growing in too many different directions. Clearly we’re at a new point now. Hopefully we’re in a trough of sorts, and there’s a new era ahead. I would hope that the entrepreneurs starting their companies in the coming years will take some of these lessons on board. Maybe you don’t need to be a world straddling behemoth to be a success?

Image courtesy of Ted Eytan.

In the past decade, the world has moved towards the ‘sharing economy.’ Adam often tried to make WeWork a part of that. It was all about building communities, then making money off those communities. Right now, we’re in an interesting moment where community is all anybody wants — and we can’t have it. At this moment, it’s not totally clear that the companies which were supposedly building the ‘we decade’ really did that. I think there is a big book-end here, in 2020, which lays bare the hypocrisy of the past decade. There have been great ideas that undergird these companies, and they’re usually ideas about connecting people. But these connections, we now see, are tenuous.

Since leaving WeWork, Adam has bounced between the Hamptons, in Long Island, and Tel Aviv, Israel. He has recently made some investments: in a residential living company, and in a car sharing company in Israel. But his billion dollar payout from SoftBank is currently tied up with lawyers right now, so he’s mainly waiting that out. I think Adam is going to sit quietly for a little while — he probably has to, for any kind of reputational management to take place. But he is not the kind of guy to go quietly into retirement at 41. Someone will give him a second chance. For all the ways he screwed up with WeWork, people like Adam Neumann tend to get second chances. People will buy in, and they’ll believe in him. He will have another act. — RW

Sir Martin Sorrell: “My grandfather cut off a cossack’s hand with a sabre at the age of 10…”

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.