The Analogue Mind: On the death and reimagining of photography

How has a camera on a mobile phone changed our experience of the world around us, asks photographer Guillaume Bonn

Words: Guillaume Bonn

Photography: Guillaume Bonn

I came from a generation that learned about the world from photography. In my case, the most important influences I had growing up were the amazing pictorial books and magazines collected by my father.

They relayed vivid adventures and tales from the furthest reaches of the globe. The photographs were taken by explorers, anthropologists, adventurers and intrepid photographers, and they captured my imagination.

Like my father and grandfather before me, I was born in Africa, and all the books I read about that continent had a special resonance. They triggered my curiosity and my desire to start taking pictures myself.

In time, I became a documentary magazine & newspaper photographer. I lived in Nairobi and travelled to every corner of the continent, witnessing and recording the region’s changes as they took place. Along the way, my own particular sense of Africa emerged, a mix of the familiar — it’s fading European colonial heritage, architecture, and enduring lifestyles — together with what I found unfolding in front of me: the continent’s devastating wars, its political dysfunction and the epic destruction of its natural environment.

I wanted to capture all of it, and I did just that for twenty years — until smartphones, Instagram, and the economic recession of 2008 combined to cripple the magazine industry, changing the world and my profession forever. When I began taking pictures, photography was about telling stories of the world around us. It could provoke emotion, action and reaction; it seemed to capture a deeper kind of truth. But now we are bombarded with so much visual information — often via videos and pictures taken with phones — that it’s increasingly hard for us to really look and see them. Instead of creating a connection to the wider world, mass photography has intellectually disconnected us.

From 2008, the magazines and newspapers that had commissioned me began cutting their budgets for documentary photography, distancing themselves from professionals with experience and knowledge and replacing them with photographs that were simply illustrative, (often bought cheaply from photo agencies), or by hiring aspiring young photographers who were willing to work for very little or nothing.

For people like myself, the only way to survive in this new landscape was to create a more individual style, and find unique stories. I strived to push documentary photography boundaries by shifting the focus in a more artistic direction.

I was personally also ready for a change in the way I saw my own photography and what I should do with it, so I was happy to embrace all the new challenges — and my personal work grew as a result.

"It feels like almost everything I see now is repetition..."

For a time, the new work I created was given the kind of attention I had only dreamt of previously. A photo essay called “Silent Lives”, about domestic servants in Kenya, was published as a twenty-five page spread in a magazine in France and ten page feature in England. Another photo essay, “Mosquito Coast”, where I travelled from south to north following the east African coastline, also worked wonders — until that no longer worked, either.

The ease of the iPhone camera has fundamentally changed the experience of taking a picture. The popularity of Instagram has redefined the meaning, impact and import of photography. Instagram has become almost the only way to look at and share photographs — a tiny rectangle on a mobile phone screen. It feels like almost everything I see is repetition. I miss the individual vision of a photographer; I miss the different styles and techniques.

Perhaps it was always destined to go this way. The sales pitch for the first Kodak camera produced in 1888 was: “You press the button, we do the rest,” guaranteeing that the picture would be “without any mistake.” In her book “On Photography”, published in 1971, Susan Sontag described the evolution of photography that had already begun, and which is accelerating today: “ The subsequent industrialisation of camera technology only carried out a promise inherent in photography from its very beginning: to democratise all experiences by translating them into images… Manufacturers reassure their customers that taking pictures demands no skill or expert knowledge, that the machine is all knowing. It’s as simple as turning the ignition key or pulling the trigger.”

I believe that individual voices and unique visions in photography have today been marginalized. The idea of challenging an audience has been replaced by servicing it; essentially the process has become corporate-friendly, a mass media for mass consumption.

The filmmaker Martin Scorsese once wrote of “the gradual but steady elimination of risk”, noting that “many films today are perfect products manufactured for immediate consumption.” It’s the same with photography.

The work of the philosopher Bernard Stiegler regarding disruption and proletarianization also demonstrates the extent to which the world is being changed, with the acceleration of digital innovation, mass mediatization and how all of it creates the standardization of our lives and the impoverishment of culture. This, in due course, also affects all trades — automation and gig employment having replaced long term work, know-how and experience.

And so, as I watch my profession disappear, I am left with the old question: what is the purpose of photography? Is it to record, to witness or to understand?

I often wonder what would have happened if no photographs existed of the death camps where six million people were killed during the Second World War. Would the world we live in today be fundamentally different?

What about James Nachtwey’s iconic portrait of a 1994 Rwandan genocide survivor with a stark starburst of a machete scar across his cheek, who looks like he has returned from hell? Or Gary Knight’s photograph of the aftermath of a battle in Iraq in 2003, with US soldiers re-organising after heavy incoming tank shelling, while one of them lies dead on the ground? Knight’s photograph looks like a painting from the Middle Ages, and is such a surreal depiction of reality that you wonder if it’s authentic or a scene from a war film. Or consider the photograph by Nick Ut of a burnt naked girl in Vietnam running away from a napalm bombing; or the photograph that Paul Watson took, at great risk to his own life, of a dead American soldier being dragged by a mob through the streets of Mogadishu.

The best example of the power of my photography was the time when my picture of a young girl who had been abused and raped by United Nations peacekeepers in the Congo appeared on the cover of The New York Times. It may have been a hard thing for the U.N. Secretary General at the time to open his paper at breakfast that day — but it changed little. The kind of abuse I had documented has carried on in Congo and in many other places around the world.

"How do we trust a photograph these days?"

I am not going to argue that photojournalism or documentary photography was ever a perfect way to understand the truth— even if, in my youth, I believed that by going to the Congo, Darfur, or Somalia, my work would alert public opinion, create more understanding and improve the lives of people affected by conflict, famine, corruption, dictatorships.

What kind of impact do these images have? Can photographs help change perceptions of wars, or of foreign policies? Who is photographing the new genocides and next ethnic cleansing? Now that print media no longer sends photographers on assignment in the way that it once did, can amateur citizen journalism (that often cannot be accurately verified) fill the gap? Should it? How to square the financial arrangements? Is it right that media outlets use these images without paying for them?

Meanwhile, manipulating images has become ever easier. Almost anything can be fabricated virtually for the purpose of politics or other self-serving interests. It’s starting to feel like the possibilities of controlling information have become so great that soon we might not be able to know the difference between a fabricated history and the real one. How do we trust a photograph these days?

Susie Linfield in her article, “The Uses and Abuses of Photojournalism”, says that, “such photographs show us that great misery exists in the world. But they cannot tell us what we most need to know, which is why these photographs fail to offer coherent, explicated knowledge because they are photographs, which is to say, they are isolated fragments of a larger truth.”

I would argue that even if photographs cannot convey much in terms of greater understanding, much less spark international action, I see photography as making an important contribution nonetheless, by inserting a footnote into the greater context of history, and, together with the work of others, becoming part of a greater knowledge.

Even if my photo on the cover of The New York Times did not put a stop to children being raped by their “saviours,” I was part of a media system that wanted me to be there, that wanted to me to document abuse, to bear witness to it, in the hope that it would stop it. That system is now defunct, replaced by the Instagram culture — an online platform that sells a product or simply promotes a version of a reality that may be so manipulated and without context that it prevents the viewer from taking away a real meaning of what they are looking at.

The filmmaker Wim Wenders, an avid lover of photography and a photographer himself, recently said; “[Photography is] a thing of the past. It’s not only the meaning of the image that has changed, the act of looking does not have the same meaning. Now it’s about showing, sending and maybe remembering. The culture has changed, it is all gone. I really don’t know why we stick to the word of photography anymore.”

So here I am again, wondering whether I need to embrace this new phase of photography, and whether it creates interesting new challenges for me.

In my early days in photography, in Africa, I used to stock up on a 100 rolls of film, food, and water, and travel two or three days to reach the place where I needed to be in order to start taking pictures.

The hardest part of the job, in those pre-internet days, was sending the film I had shot to New York in order to make the magazine deadlines. It meant physically getting it out on small bush planes flying out from remote places, and then across the world on international flights. It was an uncertain process, and sometimes it didn’t work.

Technology has changed that experience, but in making transmission instant and convenient, it has altered the way we engage with the world. Taxi drivers in their own towns no longer rely on their experience of the city but follow Google Maps instructions. In many ways, I think journalism and photography have followed the same evolution.

"It’s almost too easy. Constraint was ever the mother of invention"

The action of inserting a roll of film in a camera used to create a welcome pause that allowed me time to reflect and pay attention to my surroundings, and to decide what I wanted to photograph. It helped me think, look and see, to have a better understanding of the ways I was photographing. Technology has erased the connection, contact and engagement with the world around us. Digital has replaced analogue, virtual has replaced real.

When photography emerged in the 1840s it was a tool for recording life — the people, the landscape, events. The first cameras were big and clumsy. As technology advanced across the late 1800s and early 1900’s cameras became portable and documentary photographers set off around the world to chronicle and capture historical events as everyday life.

In the 21 century the iPhone has made photography even more mobile. It has become hyper accessible: point and shoot. There doesn’t have to be planning involved, no logistics, no limits. It’s almost too easy. Constraint was ever the mother of invention and creativity.

We have now become the film directors of our lives, the editors-in-chief of our virtual private magazines, and we no longer need the assistance of “serious” journalism via printed magazines and newspapers to be connected to the outside world in order to understand it.

Taking pictures has become about follower numbers, monetisation and feeding the beast — selling a product rather than communicating an image. We all have begun to believe that when we have a lot of followers we can influence opinions with our own versions of the truth, not dissimilar perhaps to the 1960’s, when philosophers had enormous influence with new theories that were showing us the way forward.

I think that questioning reality is the essence of the analogue mind I am talking about — a practice based on the accumulated wisdom of humanity, and one’s own experience and knowledge, where nuance and truth are not casualties in a competition to gain the approval of one’s social media audience.

The digital age has engendered a deluge of photographed images, but it has also blurred the individual vision of a photographer. Think of Sebastiao Salgado’s photographs of the Ethiopian Famine of 1983-85 and his beautification of the tragedy. Or Gilles Peress’s photographs of the war in Bosnia or the genocide in Rwanda which, by contrast, are graphic and violent. But however you try to communicate an image today, whether through beauty and colour or the shock of raw graphic reality, neither works — because we’ve been bombarded by so many images that even the beauty of the beautiful and the shock of the shocking doesn’t have the same impact.

At the same time, while there has always been a tendency for traditional news media outlets to tone down strong images in order to protect the public from being outraged or shocked by the reality of war, or the world’s miseries, the new platforms have also created barriers and filters. Society now views what it wants to, according to algorithms and likes.

Decades of self-imposed censorship by the media, perhaps especially in photography and television, had the effect, I believe, of disconnecting the viewer more from in-depth reporting and understanding of the world, paving the way for the “Instagram Style” of reporting we have now.

The Libyan war of 2011 was probably the first war covered with iPhones, And photo editors became excited at the way some photographers were using digital applications and filters that can change the colour of the captured image into something more ‘visually interesting’. Finding a new aesthetic angle to cover a story in order to get magazines and websites interested has become close to impossible these days. Even with the help of a conceptual idea it rarely works. The most recent successful example that comes to mind is the old ongoing forgotten war for minerals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which Richard Mosse photographed with an infrared film that turned every photograph pink. The story was turned into an art object that could decorate a living room. And the media and the art world went nuts for that war in pink.

"Paintings distort in the opposite way to photographs: they make grandiose"

To me this kind of approach feels closer to painting than photojournalism. But as Sontag says “if photographs demean, paintings distort in the opposite way: they make grandiose”

I tried my own conceptual approach with a series called “Warriors,” in an attempt to revive interest in the human-wildlife conflict in Africa, an important and complex issue that no one in the West really understands, which I thought I could communicate by focusing on rangers who risk their lives to save wildlife.

My idea was to isolate them from the field, where they track and apprehend poachers, often having to return fire in deadly contacts. I photographed them in full gear against a white background, moments before being deployed for their night patrols. That way I could also show how they dress themselves – with everything from camouflage gear to tree branches – in trying to achieve invisibility for self-preservation. The results are closer to a fashion shoot than anything, with the clothing the essential element. Unlike fashion, it is not a story of beauty and illusion, but it is still an attempt to tell an important story.

No publication ever published it, however. Despite my efforts to make the story visually accessible, it remains complex, and I suppose that I may have encountered what Sontag describes as “a photography that brings news of some unsuspected zone of misery cannot make a dent in public opinion unless there is an appropriate context of feeling and attitude.”

Some time ago, I started working on a project called “Shooters and Explorers”. The idea was to photograph cameras that belonged to people whose work I admired. I wanted to capture the old analogue cameras of image-makers who have in their own way been explorers — either by using photography as a way to record people and places, or because they explored the medium of photography itself. I wanted to connect the machine to the man — to create a dialogue between technology, technique and vision.

Malick Sidibe and Seydou Keita were commercial photographers from Mali who took portraits of people who came to their studios, and ventured out to shoot at weddings and parties. They did not realise at the time that they were also capturing the spirit of the 60’s and the winds of independence that were spreading all over Africa.

Sidibe’s photos of the well-dressed Malian youth at night could now easily be the theme of an Italian Vogue fashion shoot. But his pictures also illustrate the electric mood of a generation tasting their newly acquired freedom from colonial power. Their work recalls what portrait painters did in the royal courts of Europe during the 18th and 19th Centuries, by giving a glimpse of the social codes of Bamako at the time they lived. Their work is a reminder of what photography can achieve in capturing a capsule of time. It is a powerful prompt for our collective memory.

Another photographer whose cameras I photographed made it their life mission to record the last tribes and their traditions. In her book Vanishing Africa, Mirella Ricciardi re-appropriated the use of anthropological photography at the turn of the century to display the noble savage of Africa. With the help of the fast-changing times, she created a new photographic genre, dedicated to the recording of eroding life styles of primitive tribes around the African continent.

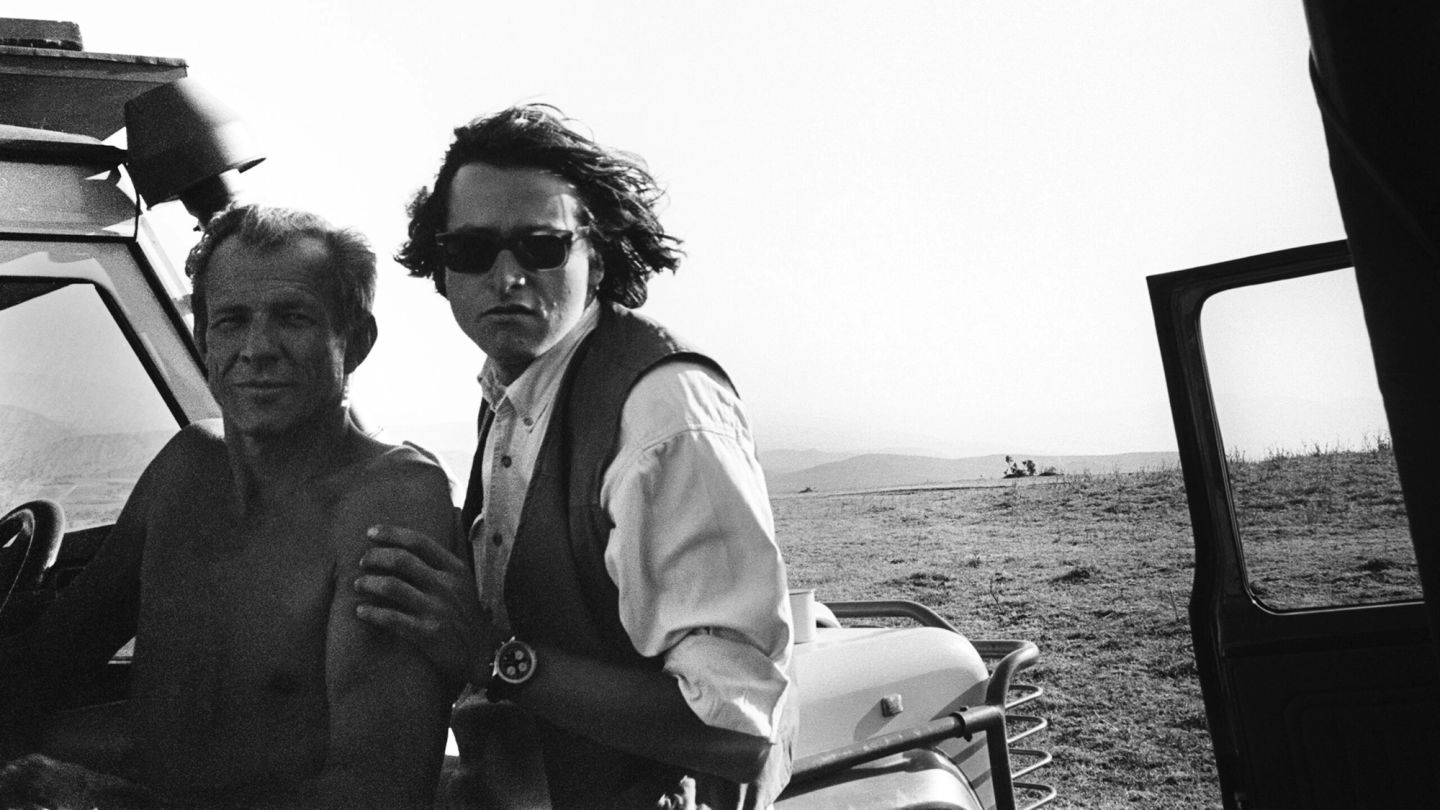

The photographer Peter Beard lived in a number of worlds at the same time, alternating between primitive conditions in the field in Africa and a jet-set lifestyle in cities like Paris and New York. His work reflected this split life — a combination of dead elephant carcasses and famous fashion models posing next to live cheetahs.

In the process, Beard produced The End of the Game, first published in 1963, which remains the most important and prophetic book on elephants and African conservation in history, and was an early effort to explain how modern forms of human progress were destroying wildlife and wilderness.

These were photographers who developed photography as language and used it as a way to describe and comment on life and times, society and history.

Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher spent forty years criss-crossing the African continent from north to south, west to east, to record for posterity all of its traditional ceremonies before they died out. In this way, photographers who have contributed to the canon of human understanding can stand on the shelf alongside great novelists, historians and academics.

"Changing cameras for me is like changing pens. It makes me write differently."

With this project it was important to me to show that, with a camera, you can carry meaning into the future. I photographed the camera of my childhood friend Dan Eldon, who had been Influenced by Beard, and experimented with collages and scrapbooks, but also ventured into the photography of war. We both went to Mogadishu in 1993 to record the US-led invasion called “Restore Hope,” which had started as a humanitarian mission, and ultimately turned into a hunt to arrest and kill a warlord who had refused to kneel down to the United States of America. Dan was killed there a month after I left, at the age of twenty-two, doing his job and verifying facts to bring about a better understanding of a very complex situation.

Recently I read that the language you speak determines how you think. In the same way I think the camera a photographer decides to use, in part, determines his vision. The different cameras I have used over the years have created different ways of telling the story I am trying to communicate. Changing cameras for me is like changing pens. It makes me write differently.

The photographer Gilles Peress said in an interview back in the 1980s that “An image has several authors: there is yourself; there is the camera (because each camera speaks in a different way); there is reality (because reality speaks very forcefully through photography); and then there is the viewer — who makes his own interpretation of what’s happening.”

In describing the analogue mind I don’t mean to denigrate technology. It’s not about whether you use a digital camera or still use film. It’s about a generational shift in the way of thinking. For me, the analogue mind comes alive when people try to photograph or write or think or engage with the world using their own vision and intellect and feeling. There is no substitution for real life experiences. Technology can help with execution — but it will never provide the inspiration or the concept.

The photographs in this series are my homage to analogue photography. But they also contain a longing for a bygone era, which held a certain way of being, thinking, creating and understanding: a time when some kind of ‘truth’ could still be told by a camera.

Guillaume Bonn was born in Madagascar and grew up in Kenya and Djibouti. He studied Economics and, International Politics at Universitée de Montréal and Universitée du Québec a Montréal, and graduated from the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York.

Bonn was a contributor to Vanity Fair magazine (US edition) from 2002 to 2017. He was the recipient of several awards and the author of five books, including Mosquito Coast, travels from Maputo to Mogadishu., He has directed a number of documentaries, including Peter Beard: Scrapbooks from Africa and Beyond

He still takes photographs and advises organisations pursuing wildlife and environmental agendas.