Words: Gentleman's Journal

Cassius Clay, the fighting prophet from Louisville, fulfilled his threat to stop Henry Cooper in the fifth round at Wembley Stadium last night. Referee Tommy Little led the half- blinded Cooper to his corner after one minute 15 seconds of the fifth session. Blood was pumping from deep gashes above and below Cooper’s left eye. There was not one in the crowd of 40,000 who would have wanted him to continue. Clay, perhaps the fastest heavyweight in the world, did not escape completely. At the end of the fourth a terrific left hook from Cooper dumped him on the seat of his scarlet pants for a count of four. Tottered Clay was sitting there, back against the ropes, when the bell sounded. He got to his feet and tottered to his corner. Frenzied work by his cornermen got him into shape for what proved to be the final round. So Cooper who had carried the fight to Clay so bravely again suffered a night of disaster brought about by his long-standing weakness. Cooper, who won the first two rounds, and shared the third, was, I thought, ahead when Little ended his game effort to beat a man 19lb heavier and seven years younger. Cooper began with tremendous fire, hooking the 6ft. 2in. Kentuckian with his left to the head and taking the first round. He took the second. But Clay, dancing about the ring, throwing sighs of protests at Little, seemed completely happy. Carrying his hands down by his side Clay weaved about the ring. In this round his right cross, which followed two lightning lefts, opened the first cut just below the British and Empire heavyweight champion’s left eye. In a fantastic fourth round, Clay poured lefts and rights to Cooper’s reddening face. Clay sensed the end was near and got a little too cocky. As he threw a left, Cooper smashed over a left hook which dumped the American on the floor. Disappointed Clay recovered magnificently. With blood spurting out of Cooper’s wounds referee Little called a halt, examined the eye briefly, and led a sadly disappointed Cooper to his corner. Clay posed for pictures, held up his hands with five fingers outstretched to remind the hostile crowd of his prediction that he would win the fifth. The crowd booed; Cooper left to a round of applause. Back in his dressing room Clay talked of how near he had been to defeat several times. In victory, Cass the Gas became a gracious young man. He had nothing but praise for Cooper’s gameness and the power of his punching. Respect Cooper said: ‘I couldn’t see. Everything was blurred, and I have no complaints about it being stopped. But for the damage to my eye I would have won. Clay developed a respect for me.’ In Clay’s dressing room champion Sonny Liston’s manager, Jack Nilon, told Clay that he would give him a shot at the title after Liston had beaten Patterson. Clay replied: ‘I’m ready for the fight if the money is right.’ Clay complained of Little’s refereeing: ‘He allowed Cooper to hit me on the break. I won’t fight over here again with a British referee in charge.’

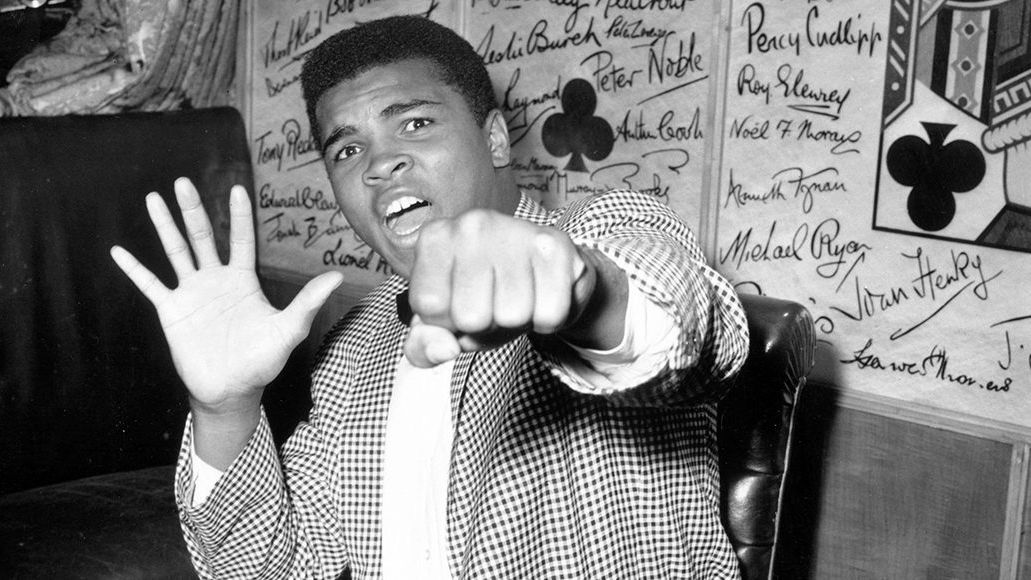

Getty Images

CASSIUS CLAY won the world heavyweight championship here tonight in a fight which is too puzzling to have a ringside explanation. The official result was that Sonny Liston retired from the contest and surrendered his title at the end of six rounds. The end came without any warning in a bout which was remarkable for lack of skill and aggression of the kind expected. When the crowd was cleared form the ring it was announced Liston had injured his left shoulder and could not continue. This was almost unbelievably because Liston had shown no signs of injury except for an eye cut in the third round which had quickly healed.

When the M.C. was able to make an announcement he said that Liston had dislocated his shoulder and could not answer the bell. So the result is that Cassius Marcellus Clay, at the age of 22, won by a technical knockout in the seventh round of a contest that had almost no incident or excitement. At that point the referee had scored the fight as a draw and one judge was for Liston and one for Clay. So after six rounds neither fighter had a majority vote. All I can say is that after Clay’s wretched performance at the weigh-in and Liston’s almost useless defence of his title there is much more to be investigated before a sound opinion can be given.

Clay is not a good champion but that makes Liston’s vanishing act amid the boos of the crowd even more mysterious. It was not really Clay who had deceived us but Liston. Clay did not forget his pre-fight threat to taunt the boxing writers who laughed at his poetic prophecy that he would beat ‘the big bear.’ Surrounded by his handlers, friends and well-wishers, he walked to the ropes, leaned over and yelled down into the Press benches: ‘Eat your words.’ Dr. Alexander Robbins said Liston’s corner had made the decision to not come out after the seventh round. ‘I didn’t stop the fight, they did.’ He said Liston told him that he could not lift his left arm above the shoulder after injuring it in the first.

Talking of the fifth round, when he hardly threw a punch, Clay said: “I looked bad because I could not see.” ‘They will say it was a fix, but it can’t be because Liston quit.’ Asked if he would fight Clay again, Liston replied: ‘I don’t know. I will have to think about it.’ Clay was first into the ring. There were only a few cheers as he slipped between the red ropes.

Clay drove over a volley of punches that hurt Liston at the start of the third. A cut opened under the Liston’s left eye but he tore after Clay and pounded him to the body. The cut looked wide and deep. Clay moved nimbly around the heavy-footed champion, but Liston got in a left and right to the body then a hard left to the jaw. Liston drove over a solid right and left to the jaw, but the punches did not seem to bother Clay. Liston’s seconds had an ice bag on the champion’s cut and swollen left side of the face. Clay blinked as if he could not see at the start of the fifth. Liston smashed him to the body with both hands, but Clay got away, then held.

Clay was blinking his eyes as Liston stalked him. Clay was not punching. He was just holding out his left arm. Clay’s eyes appeared all right now. He was moving slowly away from Liston who by the sixth was very sluggish and apparently very tired. Liston the champion, weighed 15 stone 8lb. and Clay 15 stone and half a pound. It was the heaviest heavyweight fight for 22 years.

Getty Images

On Muhammad Ali’s 18th birthday, like almost ever other male American citizen, he registered for conscription into the U.S. Military. But in 1964, when he was 22, he converted to Islam – but never changed his draft status with the Army. Then, on April 28th 1967 after an epic rise to fame as Heavyweight Champion, Ali’s career came to a screeching halt after he refused to be drafted into America’s war with Vietnam, on the grounds of being a self-confessed conscientious objector. That day, at his scheduled induction into the U.S. Armed Forces, he refused to step forward to his name three times, even after he was warned of the implications in doing so. He was subsequently arrested and almost immediately striped of his title as Heavyweight Champion. He also wouldn’t be allowed back into the ring anytime soon, something that he fought a losing battle against with America’s Supreme Court until 1971, when he was set free.

He always cited this new religious stance on his refusal to draft: he was now a non-violent Muslim and entering into a war fought by other religious would be going against Allah’s word. ‘I have been warned that to take such a stand would put my prestige in jeopardy and could cause me to lose millions of dollars which should accrue to me as the champion,’ he said to the court. Scandalous, yes, but something that he refused to change his stance on, even after the pressures of legal punishment loomed.

Ali was convicted of draft evasion on June 20th that same year after only 21 minutes of deliberation from the jury. He was sentenced to five years in prison, fined $10,000 and banned from boxing for three years. He never actually served his prison sentence after his case was appealed, and he returned to boxing in October of 1970 and a year later had the first loss of his professional boxing career.

Getty

The sun had the audacity to rise over Central Africa yesterday while Mr Muhammad Ali was still speaking. His message was really quite trivial. He will require $10 million, he informed the universe, to perform his next miracle in the boxing ring.This works out at something slightly over £4m an hour, or, alternatively, precisely twice as much as he received for exposing George Foreman as not quite the immovable object we thought. Naturally, we shall pay for it. We shall rob banks, surrender life policies, shortchange widows and sell the new dishwasher to raise it. His recapture of the world heavyweight title here, on a morning the memory of which I shall take to the grave, entitles him to name his own price.

By the eighth and providently last round he had, according to a communal roundup of statistics, hit Foreman 65 times flush on the face. It was then, from an entrenched and contemplative position, that he saw an opening which lasted as long as it takes to fire a hair-trigger pistol. Foreman is a man of ingenuous honesty. ‘A boxer,’ he said when his mind was functioning again, ‘never sees the big one that hits him.’ What hit him, in fact, was a Bren-gun burst of quick blows, a left hook that spun him round into the real line of fire and a right that put him on the floor for the first time in his professional career. He sprawled there, blinking and subconsciously mouthing the count to himself. He had not one chance in 50 of getting up again. It was like watching a tank going over the edge of a bridge in slow motion. He became so confused by Ali’s tactics that he finished the fourth round hurling wild swings into the air, and later missed so badly with the punch that was meant to finish it all that he almost went through the ropes. Ali slapped him on the bottom. Throughout the fight he talked to Foreman in all the clinches and carried on a running conversation with a black American reporter in between rounds.

In the fifth round he indulged in a piece of exhibitionism so dangerous that it would not be tried by the resident professional fighting farmhands in a fairground boxing booth. He sagged back so far on the ropes that he was almost in the laps of the TV commentators. And there he stayed for well over a minute, defending himself from Foreman’s frantic hitting only with his forearms and cupped gloves. Ali took the wildest liberties and still rode back to the world title he regards as personal property with a performance of total genius and physical courage. The fight that was reckoned to be his $5m retirement pay-off went precisely as he bragged it would. ‘I shall be the matador and Foreman the bull,’ he told his Zairois brothers last week. The metaphor was exact.

Ali went down, too. Ten seconds after Foreman was counted out, he was knocked down as his faithful leaped into the ring. From then, long into the dawn, he was besieged. ‘I’m going to haunt boxing for the next six months,’ he shouted. ‘I’ll talk to the man who first offers me 10 million dollars.’ You may say a man requires supernatural powers to command such a sum. But maybe Ali has. At breakfast the sun went in and the rainy season started.

A gaggle of pretty girls got aboard an elevator for the press center in the Bayview Plaza Hotel, where they had been working for the last ten days. ‘It’s over,’ one of them said, ‘and we’re glad.’ Were they satisfied with the ending? ‘No,’ they said, ‘no’, every one of them. ‘How about you?’ a girl asked a man on the lift. ‘I’m neutral,’ he said, ‘but I’ll say one thing: Joe Frazier makes a better fighter and a better man of Muhammad Ali than anybody else can do.’ ‘Right,’ the girls together, ‘that’s right.’

A small, strange scene came back to mind. It was two days before the fight and Ali lay on a couch in his dressing room, talking. If this had been a psychiatrist’s couch it would not have seemed strange, but he wasn’t talking to a psychiatrist and he wasn’t talking to the newspaper guys around him. He just lay there letting the words pour out. ‘Who’d he ever beat for the title?’ he was saying of Joe Frazier. ‘Buster Mathis and Jimmy Ellis. He ain’t no champion. All he’s got is a left hook, got no right hand, no jab, no rhythm. I was the real champion all the time. He reigned because I escaped the draft and he luckily got by me, but he was only an imitation champion. He just got through because his head could take a lot of punches.’

Why, listeners asked themselves, why does he have to do this? Why this compulsion to downgrade the good man? It had to be defensive. He was talking to himself, talking down inner doubts that he would not acknowledge. He will never feel that need again, and he never should. If there is any decency in him he will not bad-mouth Joe Frazier again, for Frazier makes him a real champion. In the ring with Joe, he is a better and braver man than he is with anybody else.

Muhammad Ali loves to play a role. He is almost always on stage, strutting, preening, babbling nonsense. But Frazier drags the truth out of him. Frazier is the best fighter Ali has ever met, and he makes Ali fight better than he knows how. They have fought three times. In the first, Ali fought better than ever before, and lost. In the third, he fought better still. This one ranks up there with the most memorable matches of our time – Dempsey-Firpo, Dempsey’s two with Tunney, both Lewis-Schmeling bouts, and Marciano’s first with Jersey Joe Walcott.

It was really three fights. Ali won the first. Through the early rounds he outboxed and outscored Frazier, doing no great damage but nailing him with clean, sharp shots as Joe bore in. The second fight was all Frazier’s. From the fifth round through the eleventh he just beat hell out of Ali. When the champion tried to cover up against the ropes, Frazier bludgeoned him remorselessly, pounding body and arms until the hands came down, hooking fiercely to the head as the protective shell chipped away. When Ali grabbed, an excellent referee slapped his gloves away.

Then it was the twelfth round and the start of the third fight, and Ali won going away. Where he got the strength no man can say, for his weariness was, as he said, ‘next to death.’ In the thirteenth a straight right to the chin sent Frazier reeling back on a stranger’s legs. He was alone and unprotected in mid-ring, looking oddly diminished in size, and Ali was too tired to walk out there and hit him. Still, Ali won. This evening Ali dined with President and Mrs. Ferdinand E. Marcos in the Antique House. Frazier was also invited but he begged off, sending his wife instead. Afterward the winner disappeared but the loser had several hundred guests at a ‘victory party’ in the penthouse of his hotel. Like a proper host, he shaped up, trigged out in dinner clothes with dark glasses concealing bruises about the eyes.

‘There was one more round to go, but I just couldn’t make it through the day,’ he told the crowd. ‘Hey, fellas, I feel like doin’ a number.’ That quickly, the prize fighter became the rock singer. ‘Lemme talk to this band a moment, because I sure don’t want to get into another fight tonight.’ Then he had microphone in hand. ‘I’m superstitious about you, baby,’ he sang. ‘Think I better knock-knock on wood.’ He did a chorus, he urged everybody to dance, and then a member of the Checkmates took over. The Checkmates are a trio and at the fight they had sung the Star-Spangled Banner in relay. ‘We are all here tonight,’ the Checkmate said, ‘because we respect a certain man.’ He got no argument from listeners. They all stood smiling, watching Joe Frazier dance at his own funeral. Extracted from The Very Best of Red Smith (Library of America)

Was it the Greatest Sting of all time? Did Muhammad Ali set up the situation here for his Mardi Gras goodbye? The question has to be asked after Ali made a fool for 15 rounds of Leon Spinks, who had beaten him seven months earlier. If it was a Sting, Paul Newman’s enterprise in the film was minor league. Here 70,000 people paid $6m, for Superdome tickets. American TV alone paid another $6 million, while the worldwide ratings were two million. What made it so attractive was the Third Coming. Ali’s attempt to become the first man to hold the title three times. To achieve that he first had to lose it the second time and the verdict to Spinks in Las Vegas by the three judges was 26-19. So how could ageing Ali not only reverse the decision but do so by a 31-12 span?

What creates the suspicion is Ali’s attitude. If there are arguments about his rating among the all-time heavyweights nobody will deny him a place alongside Barnum and Bailey as a promoter. The line between showman and conman can sometimes be barely distinguishable but I do not believe it was crossed. Rather it was that Ali took Spinks too lightly the first time, then spotted the possibilities and took spectacular advantage. Cleverly, and alone, he built a fight plan which divided his limited energy into 15 sections. Then he danced all night and the younger man never got near him. As a fighter it was repetitive but as an occasion – not knowing whether Ali could keep it up – it was tense and memorable. It was his finest and probably his final hour. His comments on his future ranged from ‘I’m quitting’ to ‘I’m not quitting.’ Anyone looking for confirmation of either, can find a telling quote or two in support. Right now his mind is made up to go but he intends to keep in reasonable shape and make an announcement soon. A good reason for delay is that to retain his status is to assist him in other enterprises. It is possible that some monumental offer will change his mind but right now he knows he cannot hope to beat a good young fighter like Larry Holmes, who is recognised as champion by the World Boxing Council. Who else would be acceptable as an opponent? Where could they find another Spinks? If there was a sting it was to put up Spinks in the first place after only seven professional fights, then to persuade Ali to underestimate him. Now, after nine fights, Spinks may also retire. He was booed all the way to the ring and his handlers were reaching the climax of a long series of squabbles.

Had Ali planned it this way it could not have been better. Should he attempt another farewell it could only be an anti-climax. Can Spinks get himself together again, especially now that his £2 million purse has provided what should be a pension? For Ali there will always be plenty to do in life.

Getty Images

Muhammad Ali is unlikely to be allowed to fight world heavyweight champion Larry Holmes this summer because of allegations that the veteran challenger is suffering from brain damage. Ali scoffs as the suggestion that he could be going “punch drunk” despite persistent rumours in Newspapers that his speech is becoming slurred – one of the early signs of trouble. And now some doctors in the United States and Britain who have heard Ali on TV believe that the apparent deterioration has recently become pronounced. I noticed the slurred words in Ali’s last big appearance on British TV some months ago, even though his close friends ridicule any idea that The Greatest is in danger of becoming ‘punchy’. Medical examination could prevent Ali bidding for his fourth world heavyweight crown against Holmes, who holds the World Boxing Council title, for a personal fee of £4 million.

In nearly 20 years as a professional, Ali has grossed around £35 million. Yet he is still comparatively poor, having had three wives and several children and given much of his earnings to Muslim charities. He has also gathered more hangers-on than any other champion. Ali persists on training for what he calls his “Fourth Coming,” although the plans to stage the fight with Holmes in Rio de Janeiro in July have fallen through. Now he will not be able to fight again without undergoing a thorough scanning test for brain damage. These conditions would be imposed in the United States and Britain and most other countries controlled by the World Boxing Council. Committee President Hose Sulaiman ha already made it clear that Ali will not be allowed to box under their jurisdiction without s complete check-up. And Ali’s parents have both pleaded with him to give up fighting for fear of injury that could end a great career in tragedy. Dr Ferdie Pacheco, Ali’s personal physician, fell out with him over his decision to carry on. He told me, ‘We are no longer close friends because I refuse to be a apart of a great fighter going on to destroy himself. ‘Once he feinted and ducked blows, but for too long now he has been taking big punches. He is too old to go on fighting. Bob Arum, New York’s top boxing promoter said, ‘I don’t know about brain damage, but his kidneys are in such bad shape that he suffers agony even after sparring bouts. ‘After all, he’s been taking punches to head and body since he was a kid of 12.‘He frequently passes blood after fights and if he doesn’t quit soon, he may never lead a normal life again. He said: ‘A guy coming up to 39 has to be a masochist to try to recapture his lost youth. All the money in the world is not worth the risk.’ Henry Cooper told me last night: ‘I hope my old friend never fights again. He’s too old. He’s taken a bit of stick in recent years, and if he fights again he must risk brain damage

I hope my old friend never fights again. He’s too old. He’s taken a bit of stick in recent years, and if he fights again he must risk brain damage

Getty Images

There was simply no one like him; no fighter as thrilling, no voice as challenging, beguiling or defiant, no American so universally admired. The death of Muhammad Ali in a Phoenix hospital on Friday night stirred a worldwide wave of shock and regret at the passing of an incomparable champion. Ali was 74 years old and had been suffering from Parkinson’s syndrome for decades. He had been hospitalised several times in recent years and died of respiratory problems related to his disease.

It was a measure of Ali’s appeal that presidents, princes and pop stars united with countless ordinary fans yesterday in stirring tributes to his life and expressions of grief at his death. Whether it was David Cameron hailing him as a ‘role model for so many people’ or the pop star Madonna mourning ‘This man. This king. This hero’, there was no mistaking a sense that a giant had passed; that the heavyweight boxer born Cassius Marcellus Clay in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1942 had somehow struck a chord far beyond the reach of ordinary humans.

In Louisville, where he is expected to be buried, fans were placing handwritten signs that read ‘RIP Champ!’ and declared Ali to be the ‘greatest of all time’. Flags in the city are flying at half-mast. At a concert in California, the singer Paul Simon was performing his hit song The Boxer when he paused before the final verse and announced to groans of dismay from the audience: ‘I’m sorry to tell you this, but Muhammad Ali just passed away.’ He finished the song, voice breaking. Yesterday Ali’s daughter Hana posted on Twitter that as her father died ‘we all tried to stay strong and whispered in his ear, ‘You can go now.’ All of us were around him hugging and kissing him and holding his hands, chanting Islamic prayers.

‘All of his organs failed but his heart wouldn’t stop beating. For 30 minutes his heart just kept beating.’ Yet there was much more than sporting excellence to a life once summed up by an American sports writer as ‘so brassy and daring, so filled with wonders and adventure and so enlarged by the magic of his personality and the play of his mind’. Ali, a descendant of slaves, turned his back on his polite Baptist upbringing, embraced Islam, changed his name and for a long period became hated by whites across America for his outspoken views on race and the Vietnam War.

His refusal to be drafted into the US army earned him a five year jail sentence (later overturned on appeal) and the loss of both his heavyweight title and his boxing licence. The Kentucky legislature branded him a traitor after he announced: ‘I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.’ Some of those close to Ali believe that his Parkinson’s began to develop several years before he finally hung up his gloves in 1981. Davis Miller, one of Ali’s biographers and co-curator of the current O2 exhibition in London devoted to Ali’s life, said yesterday that the boxer’s ‘walking on the street was a little clunky and his speech was markedly slower’ as early as 1975 — the year Ali went 14 jaw-jarring rounds with Frazier in Manila.

The gloves are going to jail? The gloves ain’t done nothing. Yet.

The syndrome has been linked to boxing, but he once told Miller his Parkinson’s helped change the way he was viewed after years of controversy. The disease ‘allowed people to care about me even more deeply… I’m more human now. It makes me like everyone else. It’s a gift.’ Among the many stories told and retold of Ali’s wicked wit yesterday was one about the boxing gloves he used for his 1975 fight with Joe Bugner, the Hungarian born British-Australian who became European heavyweight champion. Told by an official the gloves were being stored in a jailhouse safe until the fight ‘to make sure nobody tampers with them’, Ali replied: ‘The gloves are going to jail? The gloves ain’t done nothing. Yet.’

This article is taken from our July/August issue and was edited by Adam Thorn and Daniel Tucker. Subscribe to the magazine here.