Words: Gentleman's Journal

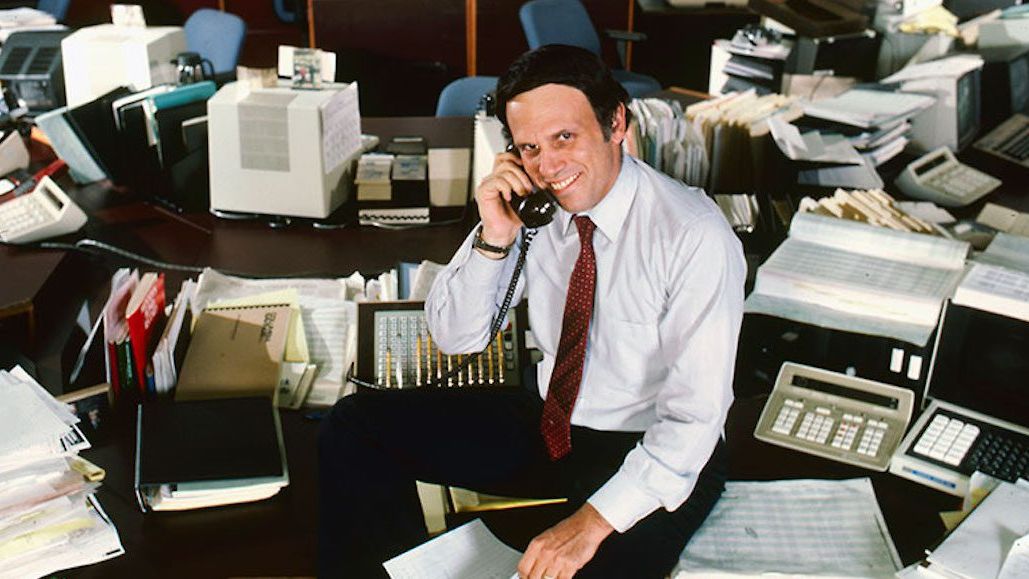

Scrolling down the personal website of the soi-disant ‘philanthropist, nancier and medical research innovator’ Michael Milken is an odd experience. The photographs of ‘Mike’ – as the site’s text chummily calls him – portray a square-jawed, broad-shouldered man with a shining bald pate and a perma-grin stretched to the point of pain. Videos show him in conversation with the likes of Tony Blair and Bill Gates, and long blocks of text detail his Milken Family Foundation’s laudable history of charity work. You’d be forgiven for imagining you were reading about a latter-day Mother Teresa.

Not in a million years would you guess that as the brains behind investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert during the 1980s, this well-connected do-gooder once played an instrumental role in bringing the US economy to its knees.

Milken was born in the quiet, middle-class town of Encino, California less than a year after the end of the Second World War. It’s easy to make generalisations, but the significance of his origins is manifest; the post-war generation he belonged to would change the world, and nowhere could be more emblematic of the economic, political and social revolution it wrought than Milken’s home state. California has a GDP of almost $2 trillion – were it an independent country, it would now be the world’s eighth-largest economy. It is home to more millionaires –and indeed billionaires – than any other sub-national entity; significantly, though, it also has the highest poverty rate in the United States

It is not clutching at straws to state that this schizophrenia of wealth is only an extreme microcosm of the culture that Milken and his followers ushered in during the 1980s.

Milken is an intensely private individual, and as such we know little of about his early life. His father, an accountant, provided a comfortable but unremarkable life for his family. Michael, who is Jewish, attended Birmingham High School (where somewhat improbably, he was head cheer-leader) before going on to study at Berkeley. Going bald in his teens only amplified his already reclusive character traits, and he distinguished himself by working harder and longer than his contemporaries: ‘I don’t know if I’m smarter than anyone else,’ he would later tell Frederick Joseph, CEO of Drexel Burnham Lambert, ‘but I can work 25% harder.’ The first real signs of his unique abilities became apparent after he began a post-graduate course at the Wharton School of Finance in Pennsylvania, where he studied bonds.

Investigating a number of once-great blue-chip corporations fallen on hard times, he realised something extraordinary; the big Wall Street credit agencies had downgraded the bonds of these ‘fallen angels’ from AAA to C-grade (‘junk’) status, thus attaching a stigma based on past performance rather than on their assets or any potential returns they might one day yield. They were dirt- cheap, and the prospective profits from a massive gamble on them would be colossal – that was why those who traded in them preferred to call them ‘High-Yield’ bonds. As Milken saw it, the ratings agencies were blinkered, too willing to play it safe – and investors too short-sighted to defy their influence, scared of being tainted with the indignity of such a gamble. A lightbulb had gone off under his ill-fitting toupée; essentially, Milken had realised that all that was holding the existing order in place was snobbery.

New York Times

From here on in, Milken developed a unique ability to sense changes in the financial world that others were too lazy or unimaginative to detect. After excelling at Wharton, he began work as a trader at an old-guard investment bank called Drexel Firestone, where he was charged with researching low-grade bonds. As Michael Lewis recounts in Liar’s Poker, his gripping account of working at trading firm Salomon Brothers (taken over by Milken in 1987) in the 1980s, Milken was out of place – ‘he lacked both tact and couth,’ and his ill-fitting wig ‘looked as if a small mammal had died on his head.’ The Californian Jew of unremarkable extraction in a sea of Ivy League-educated East Coast WASPs would quickly learn to turn his outsider status into a strategic advantage.

Milken developed a unique ability to sense changes in the nancial world that others were too lazy or unimaginative to detect.

The company merged several times in the mid-1970s, becoming first Drexel Burnham and then Drexel Burnham Lambert. These changes allowed Milken to exploit the company’s new structures and he eventually approached his superiors with the intention to let him create a designated high-yield bond department. They recognised his obvious intelligence and decided his plan, despite the negative connotations of such ventures, was worth a gamble – give him a small amount of capital to play with, they gured, and let him get the fantasy out of his system. They could have had no idea what they’d let themselves in for: by 1976 he was earning 100% on the capital provided him to run his bonds operation. This was unprecedented – almost overnight, he’d become Drexel’s most important employee, and he and his department were given carte blanche to do as they pleased. Representative of this was his hugely symbolic gesture of moving his operation from New York to Los Angeles – the outsider had not only shaken up Wall Street, but taken it home with him.

From his new HQ at 9560 Wilshire Boulevard, Beverly Hills, Milken began targeting struggling money managers who invested in pension funds and life insurers. These individuals needed to create high returns in order to attract the new clients who might allow them to stay in business, and junk bonds offered a quick and easy solution. Soon, Drexel was delivering them $50 million for every billion they had in their company portfolio – which would itself expand exponentially. Buying bonds from companies with low credit standing was a huge risk – but, as Milken had assessed, if you cast the net wide enough, the odds would stack in your favour. Why make one expensive investment with low interest rates in a ‘safe’ institution when you could make a killing buying bonds in ten companies deemed to be on the brink of insolvency?

Whether or not these doomed businesses managed to turn around their performance would be irrelevant – the mark of a cash injection from a successful investment bank would be enough to make the price of their bonds soar. ‘In short,’ as Michael Lewis writes, ‘junk bonds behave much more like equity, or shares, than old-fashioned corporate bonds’. This was capitalism as it had never before been seen.

This was capitalism as it had never before been seen

In 1980, a recession-hit America went to the polls. On the one hand was the embattled and increasingly unpopular Democrat Jimmy Carter, whose presidency had birthed a new term: ‘stagflation’; on the other was the charismatic Hollywood ham Ronald Reagan, who advocated a ‘supply-side economy’ in which tax would be lowered dramatically and the government would effectively allow the markets to run free of interference. It was an election fought on drastically simplified economic terms, and, unsurprisingly, Reagan’s sunny promises delivered him a landslide over Carter’s convoluted message of scal responsibility. The result was the fiscal equivalent of taking the police off the streets of a major city – it relied on blind faith in market confidence alone. There was now nothing to stop the strongest from doing exactly what they wanted. It was the beginning of Milken’s imperial phase.

His seemingly infallible methods meant that all of a sudden high-yield bonds were the only ticket in town. Although a certain sniffiness persisted towards the high stakes involved, bond buyers tended to perceive this as the sore reaction of the corporate clique whose power was being destroyed by the hostile takeovers advocated by Drexel Burnham Lambert. Avenues that had previously been closed to all but a few elite WASPs were ooded with ‘outsiders’ inspired by Milken’s success. Connie Bruck, whose 1988 book The Predators’ Ball: The Inside Story of Drexel Burnham Lambert caused a storm when Milken tried to prevent its publication, records that ‘in the fall of 1986, Milken had not only cast Drexel but to a large degree (Wall) Street in his image.’

Naturally, this had an impact on the market itself; as with any commodity, abstract or physical, junk bonds were subject to the laws of supply and demand – and demand was beginning to outstrip supply. A large part of their attractiveness lies in the fact that they are cheap, and any increase in their value could send an already precarious activity disastrously off-balance. Milken had a solution; since junk bonds are themselves an indication of volatility, it was paradoxically necessary to create instability in order to guarantee market stability.

He began bankrolling the infamous ‘corporate raiders’ to buy out large corporations with massive sums of debt, thereby creating new junk bonds as soon, as the takeovers were announced. People like James Goldsmith, who had practised similar tactics in Britain, and the rapacious Carl Icahn made billions from wresting control of industrial giants and gutting their infrastructure. Reagan’s laissez-faire economic policies meant that once these asset strippers had a toehold in corporate America, there was nothing to stop them becoming dominant. Revlon, Disney, Gulf, Phillips… one by one, the giants were ‘downsized’ – that is, disembowelled – from the inside out. ‘Greenmail’ – a tactic whereby the raiders would buy up huge stakes in a corporation in order to force it to buy them back at a hugely inflated price – became the norm. Share prices would rocket as if in competition to Milken’s genius.

Share prices would rocket as if in competition to Milken’s genius.

By 1986, the small stream of money Milken had diverted from the investment-grade market (as valued by the ratings agencies) in the 1970s turned into a torrential river of funds,’ observed investigative journalist Edward Jay Epstein ‘entire industries – such as cable TV, health care and regional airlines were developed through the proceeds.’ In 1970s, the junk bond market had been virtually non-existent; between 1980 and 1987, an estimated $53 billion worth of them came to market.

The seminar for junk bond traders Milken held in Beverley Hills every year – the infamous ‘Predators’ Ball’ – would feature live entertainment from the likes of Frank Sinatra and Diana Ross. ‘It’s the Academy Awards of business!’, as one organiser put it. Milken himself reportedly made $296 million in 1986 and $550 million in 1987, but seemed little interested in the ash of his contemporaries; even at the height of Drexel’s power, he was living, in a modest house in Encino, driving a humble Oldsmobile. ‘There seemed to be no personal use for the fortune Milken had built,’ Bruck writes. It was all about proving he was smarter than the rest, that he was right. But his confidence was turning to arrogance – it would later transpire that not only was Drexel involved in an intricate series of cover-ups, but it had also taken advantage of its clients, putting its own interests far above those of the people it was obliged to serve – it was, in effect, defrauding them.

Milken himself reportedly made $296 million in 1986 and $550 million in 1987

In Washington, the Reaganites had come to see the high-yield bond market as the emblem of a resurgent America, and its adherents as a new generation of Rockefellers. But despite the big talk, it was clear that something was very wrong with Reagan’s ‘voodoo economics.’ The entire idea was essentially a re-packaging of the a pyramid will lter down to those at the bottom; needless to say, it didn’t. As writer Francis Wheen observed: ‘Although the ‘supply-side’ economics had a veneer of scientific method… it was indistinguishable from the old, discredited superstition known as ‘trickle-down theory.’

Wall Street may have been booming, but Main Street did anything but – since 1980, the US’s deficit had shot up from $900 billion to $3 trillion, and unemployment gures were worse than ever. Due in part to the raiding activities of the ‘greenmailers’, American industry was in its death throes, and there was thus little evidence for any real material growth or improvement in output. It was abundantly clear that something had to give.

‘Never have so few owed so much to so many,’ Connie Bruck reports a keynote speaker at the 1986 Predators’ Ball declaring. The Churchillian aphorism was a boast, given some historical irony by what happened when they had to pay it all back. ‘Most people,’ Wheen asserts, ‘would regard it as suicidally irrational to embark on a credit-card splurge without giving a thought to how the bills can ever be paid.‘ For all Milken’s confidence that he had changed the face of nance, the securities boom was nothing but a bubble.

Compounding what some commentators including JK Galbraith were predicting was imminent economic disaster was a wave of scandals that hit Drexel in 1986. In May, a Drexel broker called Dennis Levine was arrested for large-scale insider trading, causing many to cast doubt on the practises of the mighty firm. But this was nothing compared to what was to come from his confessions. In November, Ivan Boesky, a colourful arbitrageur with whom Milken had substantial business ties pleaded guilty to the insider trading with which he had built his fortune. Boesky’s crookedness was common knowledge amongst the nancial community, and he was far from the only individual to have played fast and loose with already-lax regulation. Wall Street was nonetheless shocked ‘not at what he had done,’ Bruck explains, ‘but that he had been caught.’ Boesky – considered a ‘winner’ by Milken – had been anything but subtle, regularly buying huge amounts of shares

The SEC, chaired by then-New York District Attorney Rudy Giuliani, began investigating the names given by Boskey in earnest: chief among them was Michael Milken. It transpired that Boesky had made a payment of $5.3 million to Drexel Burnham Lambert, which the firm told the SEC was a ‘consultation fee’. It provoked enough suspicion for the authorities to pry further into Drexel and Milken’s activities. Executives at the bank saw themselves as victims: ‘one wonders if this isn’t a plot to destroy us,’ wrote Drexel’s honorary chairman Tubby Burnham.

It provoked enough suspicion for the authorities to pry further into Drexel and Milken’s activities. Executives at the bank saw themselves as victims

Throughout 1986 and 1987, Drexel – now suffering staff exoduses and beginning to lose clients – fought a PR campaign to save its reputation: ‘Junk Bonds Keep America Fit’, ran one slogan. The truth was that Drexel was well aware of numerous incidences of wrongdoing – it had been almost standard procedure – and the vain hope that investigators might somehow overlook its transgressions was all it had to go on. The bank thus sought to trivialise the violations it had made, phrasing it, as Bruck writes, that its rule-breaking ‘was not murder.’ However, if ‘Milken’s and by extension Drexel’s actions were not worth prosecuting,’ as that author qualified, ‘then the securities laws were not worth passing.’

In October 1987, the global stock millionaires were driven to automatic bankruptcy and turned inside out. Although the junk bond market was not severely affected, it was a sign that the era Milken had both personi ed and done much to shape was drawing to a close. Even if Milken and Drexel weathered the storm, their days of market dominance were over for good. In September 1988, the SEC sued Drexel and Milken for a multitude, of violations including insider trading, manipulation of stock prices and inaccurate record-keeping. Most serious of all were allegations of fraud and racketeering.

In October 1987, the global stock millionaires were driven to automatic bankruptcy and turned inside out.

Drexel Burnham Lambert pleaded guilty to six charges, agreeing to pay a ne of $650 million and to help the SEC with its investigation of Milken. The game was up, and in April 1990, Milken was cowed into a guilty plea for charges of securities and reporting violation. He was sentenced to three and a half years in prison, ned $200 million and forced to accept a lifetime ban from dealing in securities. The backdrop to this was positively Wagnerian: the Berlin Wall had been breached, Nelson Mandela released from prison and riots that would eventually lead to the ousting of Margaret Thatcher had erupted in Britain over the ‘Poll Tax’. Against this upheaval, it seemed almost incidental that the junk bond market had finally collapsed, but it was nonetheless a blow that Drexel Burnham Lambert was never to recover from. The bank staggered on for several months before declaring bankruptcy in February 1990. The ‘80s were over.

What drove Milken, then? Judging by his unremarkable lifestyle, it was not personal avarice, nor was it a desire for attention, as attested by his reclusiveness. ‘Making money for the sake of making money’ is a tired old cliché – Milken, in this writer’s view, had his sights on something much larger. ‘Michael Milken democratised capital,’ his one-time client Steve Wynn told lm-maker Adam Curtis in 1999 – his iconoclastic approach to finance was as much about destroying the illusion that high nance belonged to the chummy, established cadres of the East Coast as it was a manifestation of unapologetic greed. His objectives were nothing less than the wholesale upheaval of the existing order; he was, in his own way, as much of a revolutionary in hence on 1980s society as Margaret Thatcher. It is not unreasonable to suggest that they shared the same Randian, borderline fanatical convictions in the power of societal change through personal endeavour –‘doing business is what gives you the fuel to do good,’ as James Goldsmith put it at the time. Unlike most other businessmen, Goldsmith being no exception, Milken actually did put a lot of money into ‘doing good.’

He was, in his own way, as much of a revolutionary in hence on 1980s society as Margaret Thatcher

Keith Meyers/The New York Times

Since his release from prison in 1992, Milken has beaten serious prostate cancer and strived to rehabilitate his image. Despite the still-extant ban on involvement in the securities industry, he is still immensely wealthy, ranked 222 in 2013’s Forbes 400 list with a personal fortune of $2.5 billion. For all his aforementioned philanthropic activities (Fortune Magazine described him as ‘the man who changed medicine’), Milken’s conduct at Drexel ensures that he will remain a controversial sure. Writing in the Denver Post, journalist Al Lewis described hearing him speak about healthcare at a Jewish fundraiser in 2012. After Milken had left the stage, Lewis went over to gauge the opinion of the crowd: ‘I asked some rabbis whether it was kosher to have such a notorious white-collar criminal held up as an example,’ he wrote, ‘like a gaggle of economists, their opinions varied.’ One rabbi stated that Milken’s charitable work had more than redeemed him; another, though, responded somewhat less positively: ‘he should not have been given that stage… do you think he’d be up there if he’d been convicted of rape?’ The jury, it seems, is still out on the man once known as the ‘Junk- Bond King.’