Words: Henry Tobias Jones

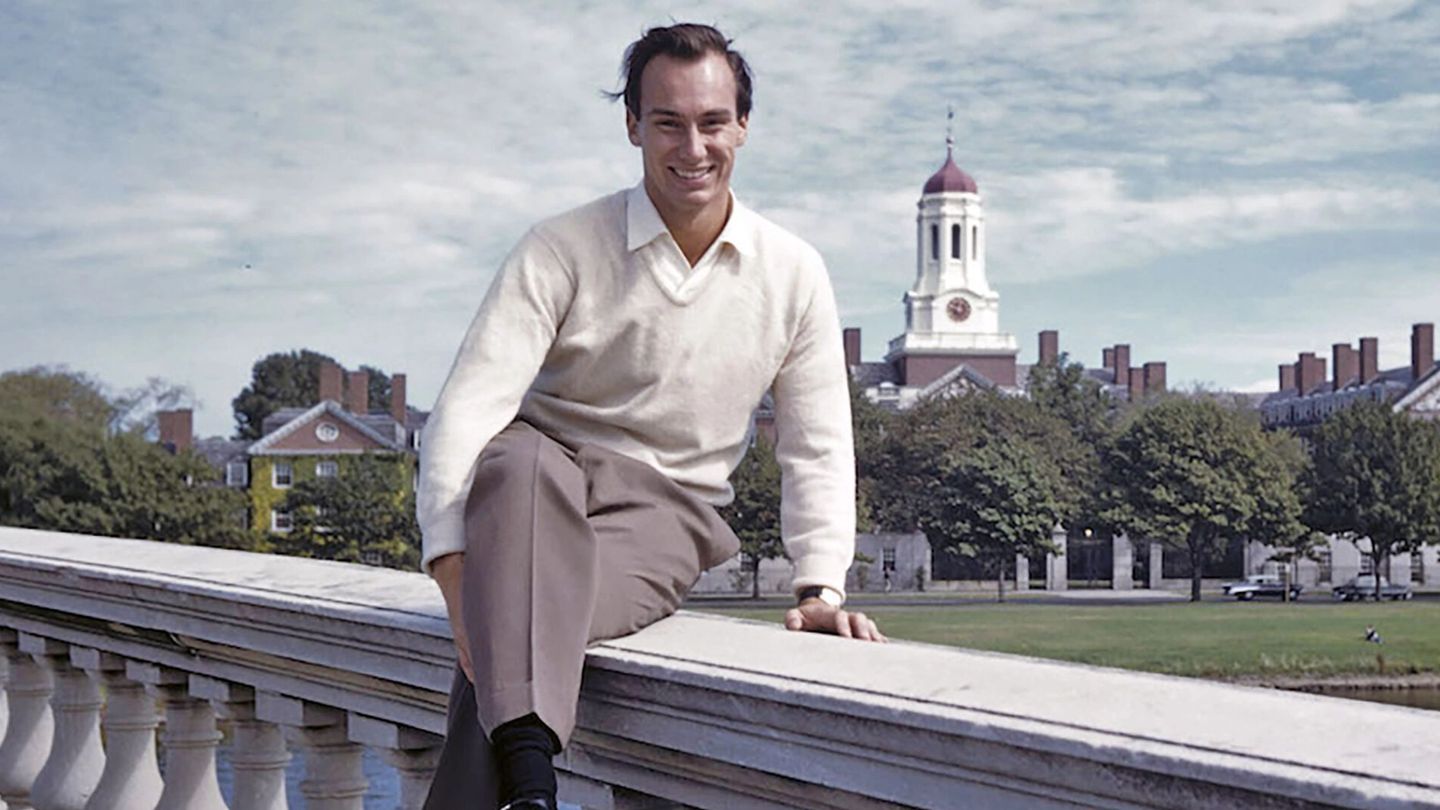

Many of Harvard’s prestigious alumni have aspired to greatness. Yet few have ever been forced to assume a mantle of great responsibility before the ink dried on their studies papers. Prince Shah Karim Al Hussaini was a carefree, football and skiing-mad student with the promise of a PhD in history ahead of him.

However, the death of his grandfather in 1957 saw young Prince Karim unexpectedly chosen as ruler and religious leader of all the world’s Ismaili muslims. In rising to the challenge suddenly thrust before him, he created a template for the next 60 years of his reign. Today the Aga Khan IV stands as one of the most highly admired yet elusive spiritual leaders of the modern age.

The Aga Khan is said to be the direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad and the 49th hereditary Imam of the Ismaili Muslims. As the Imam, he has been given the titular role of His Highness the Aga Khan, a position which he inherited from his grandfather while he was studying at Harvard University, aged just 20. He described himself as “an undergraduate who knew what his work for the rest of his life was going to be”.

Even his succession was unconventional. The Aga Kahn III broke with 1,300 years of tradition and skipped over his son in favour of his grandson. By the time he returned to his studies after an eight-month break, his classmates were calling him ‘Jesus’ and in his own words, it “was a big joke on campus”.

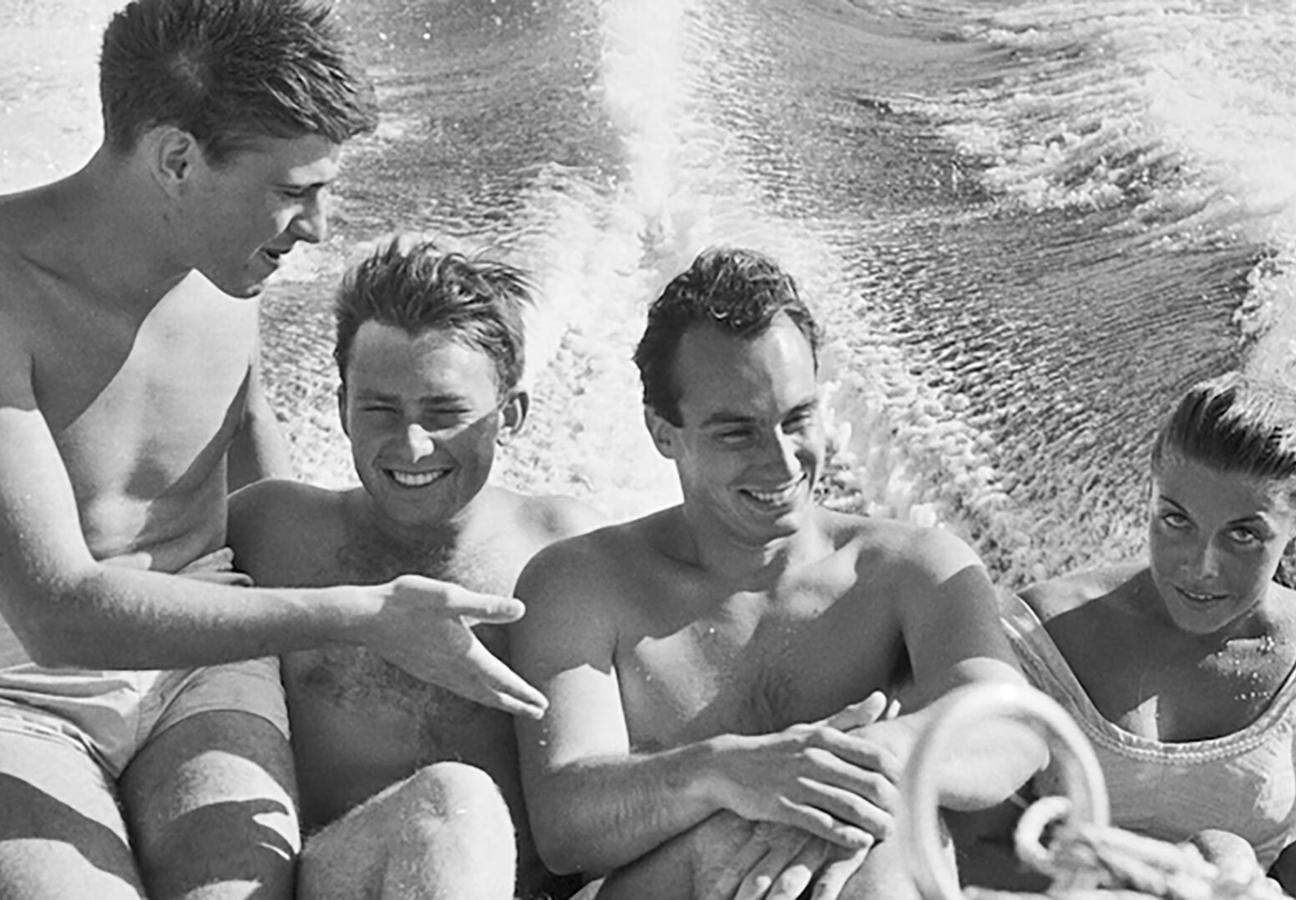

The Aga Khan participated in the 1964 Innsbruck Olympic Games

In his will, his predecessor explained that “in view of the altered conditions in the World in very recent years, including the discoveries of atomic sciences, I am convinced that it is in the best interest of the Shia Muslim Ismailian Community that I should be succeeded by a young man”.

In many ways the Atomic age Aga Khan is more modern than his predecessor could have hoped. He doesn’t share the view that religious leaders should mimic their poorest followers. He also inverts virtually every traditional Muslim stereotype.

The Ismaili are an esoteric, non-conformist strand of Islam that has more in common with Hinduism (many of the first Ismaili were Hindu converts) than it does ‘fundamentalist’ Islam. For example Ismailis are actually banned from wearing head scarves.

Nevertheless, they are still a heretical Shi’ite minority, and historically, being Ismaili has been dangerous, particularly in India, Pakistan, and now Syria, leading many to seek refuge in remote areas. As a result of both traditional and modern threats, they are a blend of modest reticence and fearful secrecy.

A poignant and recent example of their justified fear was seen in Karachi in May 2015 when a bus was targeted and fired upon by eight gunmen. 46 of the passengers were massacred, all Ismaili. ISIS claimed responsibility, leading many to speculate that the attack was religiously motivated.

But while it can be dangerous, the work of the Aga Khan also made the Ismaili into a wealthy, well-educated anomalous minority in some of the globe’s poorest regions. And much of this could not have been done without the Aga Khan’s deep, deep pockets.

Karim Aga Khan On Holiday On The French Riviera, 1959

The origin of the Aga Khan’s money is a point of intrigue and controversy. He is undeniably part of a super-wealthy elite – his well publicised 10-year divorce battle with his second wife, Princess Gabriele of Leiningen, alone was reported to have cost him £50m. He also maintained a £100 million yacht, Alamshar, which in turn was named after one of the prized racehorses.

But, although the Aga Khan was referred to as a Prince, he was unlike the billionaire Kings and Sultans that can rely on the material wealth of their countries’ natural resources. Instead his private fortune came directly from his followers.

His annual income came from the donations of 15 million Ismaili who regularly gave 10-12% of all their earnings to him. The extent of these contributions is uncertain, but estimates suggest they could equate to hundreds of millions each year. In Forbes’ world’s richest monarchs list, he was thought to be worth $800 million – with Vanity Fair suggesting that it’s closer to $1.3 billion.

Racehorse Shergar with the Aga Khan

But as a spokesperson for the Aga Khan’s Development Network explained, “people always mistakenly conflate the Aga Khan’s private wealth with the revenue of his development network”. The Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) is one of the world’s largest development agencies, spending $625 million every year on economic, cultural, and social projects – often in countries where there are no Ismailis at all.

Compared to the AKDN’s annual budget of $625 million, the Aga Khan’s personal income looked like pocket change. Moreover, since the AKDN is made up of over 70 sustainable for-profit companies, it actually makes over $3.5 billion a year – all of which is reinvested in development projects.

What really sets the Aga Khan development network aside from similar NGOs is that it isn’t a fundraising body. Thanks to the donations made by the Aga Khan’s followers, the AKDN does not need to raise funds for projects. Instead the opposite is the case, with national governments and funding institutions like the World Bank asking the AKDN help them to facilitate their projects.

“It is this work that the Aga Khan has made his life’s work,” Dr Faisal Devji, one of the world’s leading Ismaili experts explains, “and it has entirely recast the role of the Aga Khan”. The Atomic Aga Khan had, according to Dr. Devji turned his “spiritual and material wealth into a modern power, which has tangibly changed the lives not just of his followers but of people all over the world”.

Although never overtly political, the AKDN made the Aga Khan into a modern era power broker in some of the planet's most significant, and volatile regions. One particularly interesting example took place in 2002, at the height of the Afghanistan war, when the country’s already unfit infrastructure was dealt a near mortal blow.

Prince Charles and the Aga Khan in Pakistan, 2006

While Western government soldiers were still on the ground, it was the Aga Khan who decided to help by investing in a country that few others would. Helping to create the $600 million telecommunications company, Roshan, the AKDN effectively kept the country’s phones working. Now Afghanistan’s leading telecommunications operator, it provides coverage for over 71% of the population, connecting 6.5 million active subscribers.

Other projects investing in Afghanistan’s health and education systems have proved to be just as effective. The AKDN’s midwife programme has decreased the infant mortality rate from 1,600 deaths per 100,000 to less than 400.

There are far too many completed, planned, or underway projects to list, totalling billions of pounds of capital investment – from the $900 million Bujagali hydroelectric power plant that actually dams the River Nile and supplies 50% of Uganda’s electricity, to the completion of the University of Central Asia this year which is the result of over 15 years of work with campuses in Tajikistan, Kyrgyz Republic, and Kazakhstan.

It is through his management of the AKDN that you see the Aga Khan most clearly. He took the position of being a spiritual leader to millions of disparate people spread throughout many of the world’s most ethnically diverse and poorest regions – and made himself their CEO, straight from the pages of the Harvard Business School guidebook. In that sense, he was the CEO Pope for a modern religion.

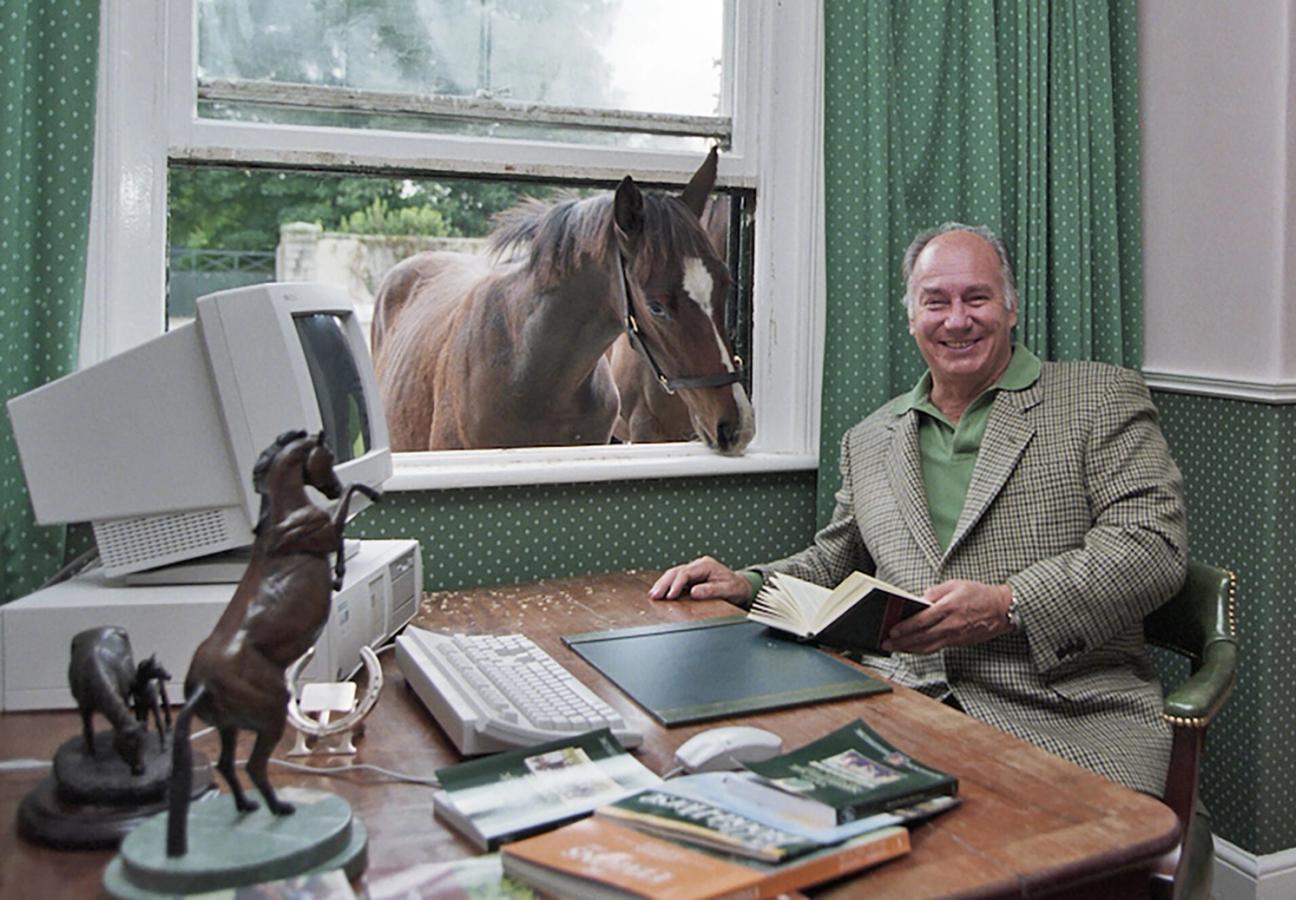

The Aga Khan on his stud farm, Aiglemont

The project that most captivated people in recent years was also perhaps the most revealing about the way his CEO management style came to shape his legacy. In 2005 the Aga Khan agreed to donate over €40 million to restore the Château de Chantilly, a pleasure palace to rival Versailles near Paris.

However, by 1998 the cost of managing the Chantilly estate had become too great for owners the Institut de France, leading to the World Monuments Fund placing it on a watchlist of endangered monuments. When it was announced that the Chantilly Racecourse, which is part of the estate, would be closing, the governing heads of France Galop, the French horse racing governing body arranged an urgent meeting with the Aga Khan.

Both his father and grandfather had been famously passionate about their horses, but when he was begged to save the racecourse, the Aga Khan simply answered: “My interests are much wider”.

The Aga Khan eventually agreed to help to restore the Château to its former glory – but only for 20 years.

“The entire area has enormous economic potential,” he explained, “which has never been thought through”. In his plans for the estate he hoped that the Château de Chantilly “will be a totally rethought, restructured cultural asset and an economic unit that will stand on its own”. The investment went towards promoting all-year-round tourism with restoration on the estate’s gardens as well as developing a major exhibition space.

But, while his development network has become the favourite of governments like France, where the Aga Khan’s money takes projects out of the taxpayer’s budget, there are regions in which his influence created some rather large problems.

The Aga Khan at the launch of "Azzurra" in 1985

In 1992 a bloody civil war erupted in Tajikistan after the predominantly Ismaili Muslim population of the autonomous region Gorno-Badakhshan declared its independence. The Tajik region remains one of the poorest and most remote areas on the planet, sharing unprotected borders with Afghanistan that are frequently used by heroin traffickers and, at that time, al-Qaeda.

Despite the best efforts of a UN task force and the Tajik central government, in 1997 many of the Ismaili militants were still resolutely refusing to put down their guns. Russian, Chinese, and Western diplomats all had vested interests in seeing a mineral rich, former soviet state achieve peace, but nobody seemed able to end the feud and Tajikistan looked set to become two permanently divided states – until the Aga Khan arrived.

Having been cut off from his Ismaili followers during the 70 year Soviet occupation of Gorno-Badakhshan, the Aga Khan was determined to bring an end to the war. Deploying his NGO’s vast resources, blended with his own spiritual authority, he asked his followers to disarm.

In what has been described as “an extraordinary and unprecedented achievement”, a non-native, loosely affiliated individual ended a civil war all because the local population had far more faith in the Aga Khan than they did the autocratic President of Tajikistan, Emomali Rahmon.

Whether his involvement in instances like the Tajik civil war influenced the world for good or bad, it is safe to say that the Aga Khan's money, his development network, and his secular and spiritual authority all contributed to making him a gentleman that has really changed the world.

Want more from the world’s most well-connected men? Read about the life and legacy of Gianni Agnelli...