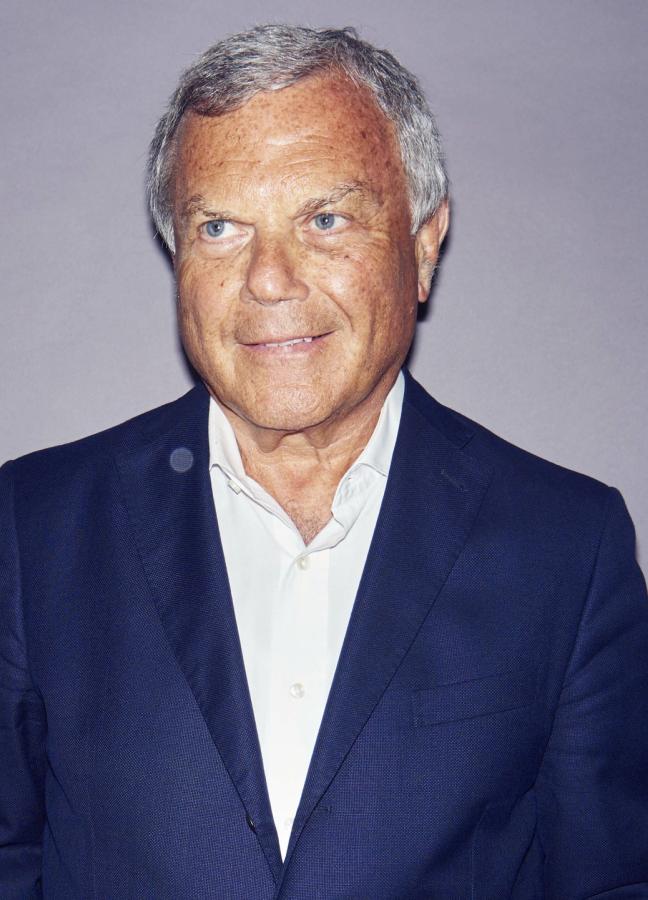

Sir Martin Sorrell: “My grandfather cut off a cossack’s hand with a sabre at the age of 10…”

For the advertising kingpin, success is in the blood

Words: Joseph Bullmore

Sir Martin Sorrell does not play golf, and he has no time for cruise ships. So when, in 2018, the advertising mogul left WPP, the almighty empire that he had built and helmed for 33 years, it was unlikely that he would go gently into that good hammock. (“People who retire early tend to vegetate both mentally and physically,” he says.) Instead, a couple of months after the acrimonious split, he founded S4 Capital — a new, data-driven, obsessively futuristic marketing company for the modern age. Two years later, it’s worth some £2 billion. S4 is named for four generations of the Sorrell family — harking back to its founder’s grandparents, who arrived in the country in 1899 with nothing.

Clearly, business for Sir Martin is not just personal — it’s historical. But it’s also pretty good fun. Recently, a director at S4 was asked how Sir Martin was finding the new venture. “It’s as if he has drunk a large potion of reinvigorating fluid,” he said. “His spirit is positively youthful — like a bright-eyed but very, very wise puppy.”

We were lucky enough to receive some of that wisdom on the latest episode of the Gentleman’s Journal Podcast, which you can find here. Do give it a listen, for the full HD Sorrell Experience™ in surround sound. In the meantime, some of our highlights below.

To me, the word entrepreneur means risk-taker. And you don’t take a risk with other people’s money — you take a risk with your own money. I fundamentally believe that you should invest in your own company. That comes from my father. I think his view was that portfolio management was a mug’s game. It was like betting at the casino. What you should do is invest in the company you know best — i.e the company that you work in. I still hold my shares in WPP and I never sold any. Building a long-term interest in a company is part of being an entrepreneur.

My father was a big influence on me. He was the son of an immigrant who came here from Kiev in the Ukraine in 1899, not speaking a word of English. They came here with nothing. My father grew up in the East End as one of six, and he had to leave school at the age of 13 to start earning money for the family.

My grandfather used to claim that he cut off cossack’s hand with a saber of the age of 10. The cossack had put his hand over the barrier into the ghetto, and my grandfather chopped it off. I think he was prone to exaggeration. When you get knighted, you have to go to the college of heraldry and design a shield. So I put a Russian bear on it for my grandparents. Our motto is “persistence and speed.”

I have two regrets in relation to my father. One is that we never went into business together. We did try, but we failed, despite having a very close relationship. And the second regret is that he didn’t have his own business. He was an immensely talented man. He could play the violin, he could quote great chunks of Shakespeare or the Talmud, and he had a phenomenal memory. For somebody who had no formal education past the age of 13, he was incredible. And I think he never really fulfilled his promise. What he did for me was to try and give me the opportunities that he didn’t have. I owe him an awful lot. Until his dying day, I used to talk to him six, seven, eight times a day.

People sometimes called me the third Saatchi brother. But actually, there was only one: Charles. Charles would regale Maurice with what we used to call the gutter speech. He would say: “if it wasn’t for me, Maurice, you wouldn’t be anywhere. You’d be in the gutter.” (Nevermind the fact that Maurice got first-class honours from the London School of Economics and Charles had left school in mysterious circumstances at an early age.) They were great times, and nothing was impossible. Every week, Campaign magazine would carry another headline saying Saatchis wins another million pounds. It was great fun.

My dad always said: find an industry that you enjoy, find a company within that industry that you enjoy, and then, when you get to 40, have a shot at building something yourself. And that’s what I did. When you get up in the morning, your heart should be in your mouth. It’s not a job. It’s more than that. And I always quote Bill Shankley: “football is not a matter of life and death. It’s more important than that.” People say you’re driven — and usually you’re driven by wanting to build something. Some business people get caught up in share price, the market value, the compensation — but that’s just the scoreboard. It’s not the reason that you do it. The reason is that you want to build something successful.

Listen to the full conversation with Sir Martin Sorrell here.

Read next: Eddie Jordan’s art of the deal…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.