Secrecy, scandal and celebrity down at Chateau Marmont

From its beginnings as an apartment complex to its recent privatisation, this is the raunchy, rumour-fuelled story of LA’s original den of iniquity

- Words: Josiah Gogarty

Many hotels are haunted, but some are more haunted than others. Some hum with the gentle chatter of conferences past; in others, glass crashes, champagne corks pop, and high society ghosts crowd the dancefloor, Overlook Hotel-style. The Chateau Marmont is one such example. People stick around, often long after they’re dead.

The Chateau — because if you’re among the initiated, there is only one worth talking about — is nearly a century old, ancient by Los Angeles standards. It has opened its doors to the stars of classical Hollywood, and their assorted hangers-on and illicit lovers; to the rock and rollers of the 60s and 70s, including Jim Morrison, who fell two stories while trying to swing between its balconies; to the Hiltons and the Lohans and the influencers they influenced. The Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn once told two of his charges that, “If you must get into trouble, go to the Marmont” — advice that might as well have been engraved above its entrance.

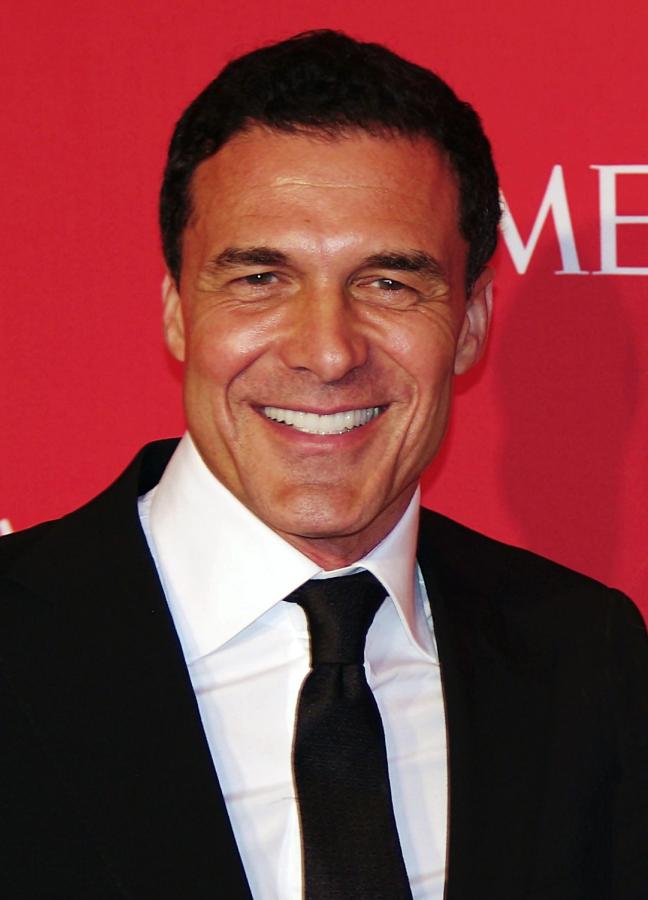

But change is now afoot at the Chateau. Most straightforward is the owner André Balazs’s intention to make the hotel members-only by the end of this year. The Chateau effectively functioned as a club already — most of its guests are repeat customers, and you’d probably need to know one of them to get a first-time reservation — so the move seems to be aimed at securing membership fees to blunt the revenue roller-coaster of pandemic hospitality.

More disconcerting are reports surrounding the treatment of its staff, nearly all of whom were let go in March with no severance pay when coronavirus hit. In September, The Hollywood Reporter aired numerous allegations from employees that the Chateau’s management had a history of union-busting, drug use, racial discrimination and sexual assault.

The Chateau has always made headlines, though it wasn’t initially intended to. In 1926, the lawyer Fred Horowitz bought some land off Sunset Boulevard, back then little more than a dirt road, with the intention of building an apartment complex for the wealthy and discreet. He chose the sprawling, gothic Chateau d’Amboise in France’s Loire Valley as his model — already an omen that the new Chateau wasn’t going to quietly keep its nose out of history. Amboise was where Leonardo da Vinci died and was buried in the early 1500s; where Catherine de’ Medici and Henry II of France started a family in the middle of that century; where Algerian anti-colonialist Abdelkader El Djezairi was imprisoned in 1848.

Like its fictional east coast counterweight, the “factual imitation of some Hôtel de Ville” built for Jay Gatsby, the Chateau Marmont’s style of architectural pastiche betrayed a hankering for the old world in a new town. It was reinforced with steel and concrete, ensuring not only that the building could withstand earthquakes, but that each room was exceptionally well soundproofed.

But this could only go so far in dampening the scandals that were soon to reverberate through it — scandals encouraged by the Chateau’s labyrinthine corridors and cubbyholes. One resident who moved in soon after its completion in 1929 complained that “The place had more doors than the fun house at Ocean Park pier.”

The Chateau’s residential phase was short-lived. The Great Depression soon set in, and Horowitz sold it to Albert E. Smith, a British film producer who converted the West Hollywood folly into a hotel. One legacy of this era has lingered: the suites have their own kitchens, encouraging the long stays — months, even years — that are a mainstay of Chateau life.

In the hotel’s first years it attracted more Californian bluebloods than debauched movie stars; it was the Gardens of Allah across the road that hosted Marlene Dietrich, William Faulkner and F. Scott Fitzgerald, the latter for a full year as his health and career rapidly declined. Then, in September 1933, Jean Harlow and her third husband Harold Rosson moved into the Chateau for five months. They were in and out of it incessantly, as were unexplained male visitors for Rosson. The pair (and the hotel) got into the papers; from then on, the Chateau rarely left them.

Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause is one of its biggest claims on Hollywood history. In 1952, after catching his second wife in bed with his 13-year-old son from his first marriage, Ray moved into a Chateau bungalow and stayed for nearly eight years. These bungalows, built on land next to the hotel bought by Smith in 1936, have grown to be just as notable as the ornate main building. Ray certainly wrung every last drop of infamy out of his, bedding stars like Marilyn Monroe, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Joan Crawford, and preying on Rebel actors Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo when they were underage. The film’s script was written and rehearsed in and around the bungalow; Ray even had the space reproduced on a studio lot and worked into the film itself.

“If you must get into trouble, go to the Marmont...”

Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski moved into the Chateau in the late sixties when they were young, besotted newlyweds, hosting parties for friends including Mia Farrow and Jack Nicholson. The pair moved into an actual house when Tate became pregnant in 1969, where that August, she and four others were murdered by members of the Manson Family. Polanski then spent his last night in America at the Chateau in 1978, before fleeing to Europe to evade charges of raping a 13-year-old girl.

Other tales are more light-hearted. On his second visit, the Austrian director Billy Wilder was put up in the antechamber to the lobby’s female bathrooms, on account of no rooms being available at short notice. Vivian Leigh was a bit more discerning about her digs, bringing along Renoirs and Picassos to “brighten” her suite up. Humphrey Bogart moved his mother Maud into the Chateau in 1938, when she was in her early 70s; she would spend her days walking up to strangers on Sunset Boulevard, telling them exactly whose mother she was. And in the late 40s and 50s, long after her film career had wilted, Greta Garbo would troop back to the Chateau after a day of walking in the hills, carrying armfuls of wildflowers with which to decorate her suite.

In comparison to its guests, the Chateau’s owners were rather minor characters until Balazs came along. But the proprietor who bought the hotel from Smith in 1942, and who had slid into obscurity until Shawn Levy’s 2019 book The Castle on Sunset, played a pivotal role in establishing the hotel’s cosmopolitan, egalitarian spirit. Erwin Brettauer was born into a German banking dynasty but fled the country on account of having a Jewish mother, eventually moving to New York in 1941.

The Chateau had always had a European flavour — Lawrence Olivier was invited to nets by the Hollywood Cricket Club when he stayed there in 1933 — but when Brettauer took over other central European exiles followed, two Hapsburg archdukes among them. A Weimar-esque tolerance arrived too. Unlike his competitors, Brettauer welcomed black guests, who quickly wove themselves into the Chateau’s tapestry. Duke Ellington was the first, appropriately naming an album he composed while wandering the hotel’s corridors Swinging Suites. Quincy Jones, Nina Simone and Dizzy Gillespie came soon after, the latter of whom learnt to putt on the carpet of Erroll Garner’s rooms.

The hotel also became something of a gay hangout. The actors Anthony Perkins and Tab Hunter began an affair after being introduced to each other by the Chateau pool in 1955; Perkins would later meet Christopher Isherwood and his partner Don Bachardy in Gore Vidal’s suite. Vidal immortalised in writing one of the Chateau’s less sophisticated neighbours: a giant cowgirl that revolved perpetually above the Sahara Hotel on Sunset Strip from 1957 to 1966. “To wake up in the morning with a hangover and look out and see that figure turning, turning, holding the sombrero — you knew what death would be like.” It was a rather more earthy stand-in for the green light that glimmered across the bay from Gatsby’s mansion.

Brettauer sold the Chateau to the property developer William Weiss in 1963, the first of a string of owners who did little to maintain its décor or reputation. It passed into the hands of Raymond Sarlot and Karl Kantarjian in 1975, who oversaw a painstaking, years-long renovation, enough to get it listed by the LA Cultural Heritage Commission. Like Brettauer before them and Balazs after, they ended up hiring Hollywood set designers for the job — probably why generations of film stars have felt so comfortable there. On a visit in 1982, Quentin Crisp reported its “leisurely, almost rural” feel approvingly in the New York Times: “When you arrive at the reception desk, it seems like the counter in a village corner shop. You expect to see a window containing glass jars full of sweets and dead wasps.”

Sarlot and Kantarjian also added more bungalows to the site, one of which gained a tragic notoriety as the site of comic John Belushi’s death by drug overdose. Belushi checked into bungalow No. 3 in February 1982, already in the throes of a heavy cocaine habit that occasionally diversified into heroin. On 4th March, Belushi was visited in his rooms, by now chaotic and filthy, by Robert De Niro and Robin Williams. Belushi was high — very high — but alive.

The next morning, he was found dead by his personal trainer. Paparazzi flashbulbs lit his body as it was removed from the premises, and overnight the Chateau went from being well-known by all the right people to well-known by everyone for all the wrong reasons. That said, the management were well-practiced enough to not alarm the people that really mattered — their guests. The actor Tony Randall was living next door to Belushi but didn’t realise anything was amiss until the coroners turned up.

In 1990 the hotel was acquired by Balazs. A wheeler and dealer by all accounts, his first job was in political PR, and he went on to make his fortune with a biotech company co-owned with his scientist father. The purchase of the Chateau was Balazs junior’s first gig as a hotelier — though as one half of a Manhattan power couple with Ford Modelling Agency scion Katie Ford, he must have had ample experience as a customer. Balazs set about dragging the Chateau into the same ballpark as its more luxurious cousins. Prices went up, ads went into Interview magazine, and the hotel’s very first bar and restaurant were opened, in 1995 and 2003 respectively.

A 1993 New York Times writeup of Sofia Coppola’s 22nd birthday set the scene. The guest list on the night included the Red Hot Chili Peppers and the Beastie Boys, Details magazine did an underwater fashion shoot, and Madonna filmed some ill-fated movie.

“What used to be the perfect place for a drug overdose has become the place to put your best foot forward,” they wrote. Even the celebrity death that happened on Balazs’s watch was more poetic than sordid. Helmut Newton, the fashion photographer who spent innumerable winters at the Chateau with his wife, died there in March 2004, crashing his Cadillac after having a sudden heart attack driving out of the hotel’s garage. One hopes it was his 83 years that brought it on rather than the task of negotiating the garage’s notoriously tight corners.

As the millennium came and went, the Chateau’s guest list and the canon of Hollywood A-listers looked less like overlapping circles on a Venn diagram and more like a solar eclipse — two spheres of influence completely aligned. Heath Ledger, Johnny Depp, James Franco, Keanu Reeves, Colin Farrell, Taylor Swift and the Kardashians all made appearances; Jay-Z and Beyoncé hosted a 2018 Oscar afterparty there, attended by the great and the good of black America (and Leonardo DiCaprio).

The hotel became the destination for branded events and fashion shows, and referenced in songs by Lily Allen, Brockhampton, Machine Gun Kelly, Miley Cyrus and Drake. Lana Del Ray has namechecked it on no less than four occasions, even tattooing its name on her left forearm. While prices continue to rise — from an average of $150 a night in the mid 90s to a minimum of $950 in 2019 — Lindsay Lohan’s bill of $46,350.04 for a freewheeling two-month stay in 2004, including over $700 for cigarettes, is unlikely to be beaten any time soon.

“What used to be the perfect place for a drug overdose has become the place to put your best foot forward…”

Kesang Ball, co-founder of the travel brand Trippin, has stayed at the Chateau twice and visited it for drinking and partying on various other occasions. “Every time I’ve been to the Chateau, I’ve always had quite a fun story to tell afterwards,” she says. On her first visit she met a mutual friend who had been living there for months, with millions of dollars in designer glass bongs lining his suite and a security guard stationed outside.

Last year she attended a Halloween party there and ended up dancing next to Paris Hilton. Balazs’s overhaul hasn’t quite sucked the soul out of the place: “There’s so many places you can go to be in an A-list setting,” she says, “but I don’t think they have the character and the integrity the Chateau has.” It remains a necessary contrast to the “really shiny, quite intense other side of LA”.

The Chateau has always been a refuge; in some cases a fortress. With only 63 rooms, it affords creative types much-needed privacy, and attracts those looking to get over domestic strife, or conversely, enjoy domestic bliss. Graham Nash, who described it as “womb-like”, stayed there for five months in 1971 after breaking up with Joni Mitchell. His song Strangers Room is an ode to the bungalow he settled in. John Wayne arrived in 1945 with his soon-to-be second wife while still in the process of divorcing his first, and Jeff Goldblum got married to his third wife Emilie Livingston there in 2014. In 1968, the Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham took advantage of the Chateau’s abundance of kitchens and cooked a full Christmas dinner for the rest of the band.

Rafael Olarra, an art director who drops into the Chateau when business takes him to LA, says its “decadent limbo” reminds him of Camino Real — a Tennessee Williams play about a titular Spanish town with no linear time, where Don Quixote, Lord Byron and Casanova parade through surreal dream sequences. Behind its high walls, “the hotel provides a safe environment to let yourself go and liberate [yourself] from all prejudice”, Olarra says.

Inevitably, the advent of social media age hasn’t passed the Chateau by unscathed. Paparazzi packs outside its gates are one thing; guests with camera phones and something to prove are quite another. The hotel makes efforts to preserve a degree of privacy — in 2011 the actress Jenn Hoffman was banned for a year for tweeting about the model Rachel Hunter acting raucously in the restaurant — but a scroll through its Instagram location tag brings up a reel of identikit models and influencers posing in various Chateau locations.

There’s also a thriving merch market: the hotel’s green tasselled key fobs are popular, and the writer and comedian Nimrod Kamer says he’s sold duplicates of the Chateau’s pool key after cloning it during one visit. The headed notepaper, which long-term guests can customise with their own name, has become another Instagram flex. The actress Jennifer Beals once found a note written on Chateau stationary tucked into her room’s Bible. “I hope you enjoy reading this as much as I do,” it read, with the signature of Hunter S. Thompson below.

All these names get exhausting after a while — and they barely scratch the surface. Take a deep breath: Lucille Ball, Jarvis Cocker, Sean Connery, Errol Flynn, Whoopi Goldberg, David Hockney, Dustin Hoffman, John Hurt, Bianca Jagger, Jasper Johns, Diane Keaton, Grace Kelly, Sergio Leone, Arthur Miller, Paul Newman, Peter O’Toole, Gram Parsons, Robert Rauschenberg, Phil Spector and Florence Welch have all stayed at the Chateau at one time or another. And the list could (and does) go on an awful lot longer.

When it’s that long, can any individual name separate itself from the accumulated notoriety of 91 years? It’s like marooning the entire cast of classical mythology on a tiny Greek island — no one’s going to get much peace. And new faces arrive with the express desire of muscling in on the pantheon: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Rick James both requested Belushi’s bungalow when they checked in. Basquiat, of course, echoed Belushi by overdosing on heroin in New York in 1988. Some of the Chateau’s ghosts must have left behind curses with their half-eaten room service.

Looking for something closer to home? These are the best London hotels for a luxury staycation…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.