Words: Joseph Bullmore

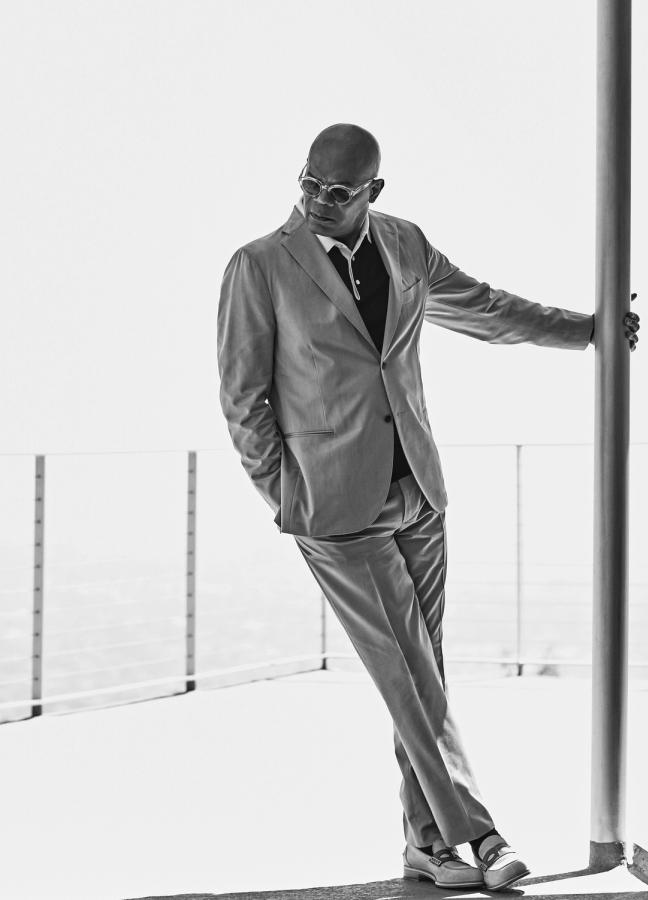

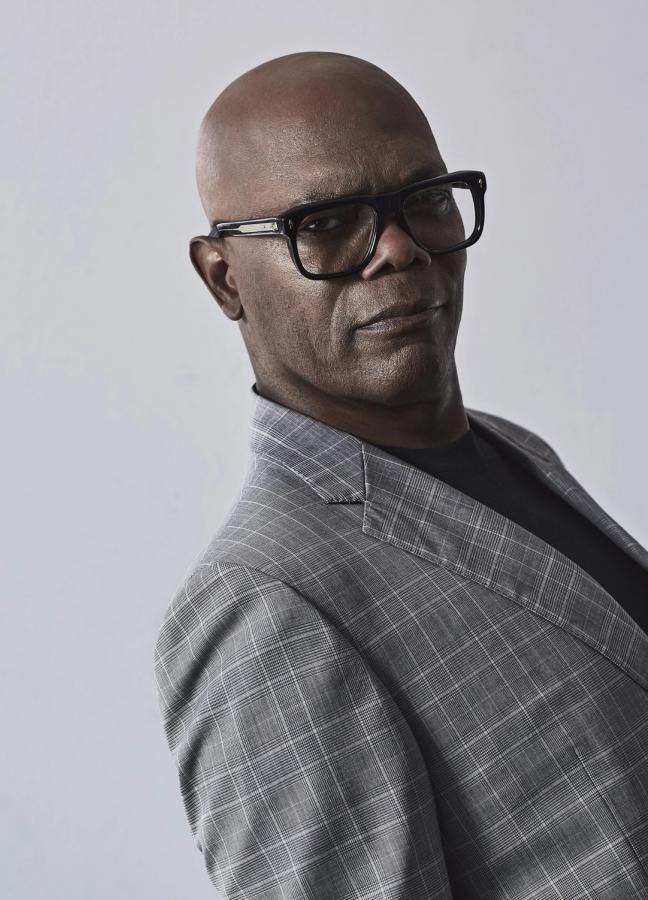

Photography: John Russo

Samuel L. Jackson is the man I want to be when I’m 72. Actually, he’s the man I want to be now I’m 30, come to think of it.

Ian Fleming and Albert “Cubby” Broccoli said they decided to cast Sean Connery as 007 because, as he left their lunch table and walked across the street, they realised he moved “like a panther”. The day after Barack Obama’s inauguration, Christopher Hitchens wrote that the key to the President’s appeal was his “feline sensibility” — he was, Hitchens said, the ultimate “cool cat”, with a matching ability to “land noiselessly on his feet”.

When Samuel L. Jackson walks into the house to greet us, on a bright and hazy March morning in the Hollywood Hills, it’s clear he’s another beast entirely — part alpha lion, part Top Cat; light and heavy at once, padding around at his own pace and to his own rhythm; King of the Jungle, but, hey, there’s room for you too.

The first thing that strikes me is how young Jackson looks. The man turns 72 this year, but he could pass for 45. (This really comes home for me when I consider that he is one year older than my father, and, no offence to my father, but very few people have called him up recently and asked him to play Shaft. For a slightly more universal reference: Samuel L. Jackson is just 18 months younger than Donald J Trump.)

"Samuel L. Jackson is the man I want to be when I’m 72. Actually, he’s the man I want to be now I’m 30, come to think of it..."

This is all the more encouraging when you realise that Jackson doesn’t stick to the usual Californian regime of endless exercise, clean eating and mineral cures. His catering request on the day of our interview lists Cheetos, Fritos and choc-chip cookies among the Fiji Water and ginger beer. “Do you have Fritos back in England?” asks the host at the West Hollywood mansion where we’re shooting. “Those are kinda greasy. I’m kinda surprised he wants those.”

But calories don’t stick if you don’t give a damn about them, and Samuel L. Jackson has no time for vanities. The man is above molecular biology, and if he eats fluorescent cheese-puffed cornmeal snacks at 10.30 in the morning, then so will you.

(Usually at this point I’d insert a little refresher course about the interviewee, followed by a short briefing on their upcoming releases in order to please the publicist and foster an environment for future working relations. The whole thing’s there just in case someone is reading this who doesn’t happen to know who the talent is. But in this case, I don’t need to say things like “the highest-grossing movie actor of all time”, or remind you about “Ezekiel 25:17” or those snakes that happened, through no fault of their own, to be on that plane, because you already know who Samuel L. Jackson is, and, what’s more, he knows it.)

Gore Vidal said, “Style is knowing who you are, what you want to say, and not giving a damn.” Samuel L. Jackson breathes that philosophy with better intonation, and with the added benefit of not being Gore Vidal. When he speaks, he speaks with this infectious half-smile on his face like he’s about to break into laughter at some inside joke, and a sparkle of curiosity in his eyes that says, “Don’t you get it yet?”

I don’t think it’s his intention, but the wisdom flows out of Jackson and into the room like osmosis, or sunlight, or the tiny clouds of fruit-flavoured nicotine vapour he exhales at various points during his off-the-cuff homilies. I’ve tried my best to distill some of this spirit below. Here are nine rules for living from a man you’ll never be, not even close, don’t bother. But you might just be a better you. See you at work.

1. Whatever you do, be a mechanic

“I don’t care what your job is, you need to understand the intricacies. You need to know the mechanics of how the thing works,” Jackson begins. “Say you want to be an actor. Well, then you need to learn the mechanics of the theatre: upstage, downstage, stage right, stage left, countercross. Everything is a valuable lesson.”

And Jackson should know. Throughout the seventies and eighties, before the man had even set foot in Hollywood, he was a consummate theatre professional, carving out multiple performances a day, on Broadway and off it, at the service of some of the greatest American writers of the past century: August Wilson, Eugene O’Neill, Charles Fuller, Tennessee Williams.

“A lot of people show up now from doing something else,” he says, a mischievous grin flashing across his face. “Like, ‘I’m good-looking,’ or ‘I played basketball for a while,’ or ‘I used to be a stand-up comedian and I wasn’t very funny.’ No. You won’t make it. The mechanics is the skill set that will sustain you even on days when you don’t feel like doing it, when you’re at work and you’re not feeling that magic.

“Sometimes you’re on set and there are actors who are clearing everybody away from around the camera because they don’t like those people on the sidelines. And I go: ‘Well, I used to do this thing where there are people on my sidelines every night — it’s called theatre!’”

Jackson laughs. “I’m always looking for an audience. The more people watching me, the better I am. That’s the damn mechanics.”

2. There's no time to be humble

“I wish that I could watch the plays I was in while I was in them” Jackson said to Time magazine back in 2006. “I dig watching myself work.” It’s a refreshing attitude in an industry where most stars claim, in cringes of humility, to hate watching their scenes after they’ve wrapped. Does Jackson buy that stance?

“That’s total bullshit. Come on, it’s a total ‘look at me’ business,” he says. “You’re saying this because you’re trying to humble yourself and do all that shit but hey you’re in a business where you’re asking people to look at you all the time, you know: ‘watch me do what I do’.

“Listen, if you want to be good, really good, there’s no time to be humble. You don’t have to put it right in people’s faces. But if you can’t stand to watch yourself work then why should people pay $12.50 to watch you work?” Jackson laughs. “I wish I could’ve seen The Piano Lesson when I did it. Or A Soldier’s Play — dynamite cast,” he remembers of the 1981 production that featured, among others, a young Denzel Washington.

I wonder if Jackson knows instantly whether his performances are good or not. Is there a kind of acid test that he applies to every scene? “I don’t watch playbacks. It either feels right or it doesn’t. And I generally do the same thing take after take after take, because I know what I want to do” he says. “You can tell from the buzz, the immediate reaction. And sometimes, some reactions, I think, damn, I wish I could have watched that!”

3. You make your own luck

“You know, there are all these adages, that ‘Luck is the perfect meeting between preparation and opportunity’,” Jackson says. “I guess it’s true. By the time my turn came, in the eighties, I had been acting on stage for years and years. I had watched that happen for other people.”

"If you want to be good, really good, there’s no time to be humble..."

“I was there when Morgan [Freeman] got plucked out of New York, in Street Smart. I was doing a play with Denzel when Denzel got plucked out, went to do the TV show [St Elsewhere], then he got the big movie after that. I was there when Fish [Laurence Fishburne] left. I knew I was in the right place, it just wasn’t my time yet.”

Did he ever think that his moment might not come? “No,” he says firmly. “When you have that feeling is when you want to get another job. I trusted in my preparation, I trusted in my luck.”

In fact, Jackson’s entire early career was based on a tiny caprice of fortune. One day, as a student at Morehouse College (where he was studying to be a marine biologist), a public-speaking professor saw Jackson stand up and speak, and asked him if he wanted to try his hand at acting.

“Mr Guthrie,” Jackson smiles. “He was doing a production of The Threepenny Opera, and he needed guys. He said: ‘Anybody who comes and plays will get extra credit in the next course.’ And I did it, and it was kind of like… ‘Wow.’ So that was the lightbulb moment. That is luck, I guess. Saying ‘yes’ to things, being open to the opportunity. You make your own luck.”

4. "As soon as you have a Plan B, Plan A is fucked"

It’s easy to write off many Hollywood stars’ success as a kind of survivorship bias; their advice as a sort of selective memory. They were fortunate to be successful, while a thousand other suckers did the exact same thing as them and never made it. Often, our heroes reverse-engineer their past after the fact so as to say: “I was always going to win. And you can too if you just follow my steps.”

However, in Jackson’s case, the advice is hard-earned and worn lightly. After all, the actor’s big break didn’t come along until he was in his mid-forties. But never in those long years in the hinterland did he once lose sight of his goal.

“Once I figured out that this was where I belonged and what made me want to get up every day, I was committed to it,” says Jackson. Soon, Mr Guthrie’s Threepenny Opera at Morehouse had morphed into other performances, and within the year an unshakeable obsession with the stage had derailed Jackson’s original plans of graduating as a marine biologist.

“My mom was like, ‘You need to take your degree and do so-and-so -and-so,’” he says. “But I’m like, ‘As soon as you have a plan B, plan A is fucked!’ So I never did plan B. Even when I got to New York and I wasn’t acting, I built sets, I hung lighting. So when I said I had an audition to go to, they’d understand and say, ‘Good luck, hurry back,’ not ‘Who’s going to wait my tables for me?’” He grins. “I never waited those damn tables.”

5. Get out of your own way

The auditions were soon bearing fruit. By the mid-eighties, Jackson had won critical acclaim for performances in The Piano Lesson and Two Trains Running, both of which premiered at the vaunted Yale Repertory Theatre.

But just as Jackson’s public image became burnished by grander reviews and bigger billings, his private life began to crumble and decay. “I was a drug addict for a lot of it,” Jackson says. “And I was doing some of the biggest plays at the height of my addiction. But I was still working. I would work every day.”

Heroin, cocaine, crack, alcohol. “I did everything,” he tells me. Yet he was still turning up to eight performances a week. “People had no idea that I was smoking cocaine because I went to rehearsal that way every day, so when I got to the theatre at night, I was just the same guy.”

Jackson’s performances in that period were strong, and many of the plays were critically successful. But none of the roles maintained the exit velocity to carry Jackson out of Broadway and into the mainstream. At one point, Jackson’s wife LaTanya told him that his performances were technically precise. “But they’re bloodless,” she said.

“That was back when I was using and I spent more time playing to the audience,” Jackson remembers. “I was always doing something to make them gasp, make them sigh, make them cry. But I wasn’t servicing the play. I was only doing what serviced me. That’s bloodless.”

Soon, Jackson’s wife and friends had checked him into a rehabilitation facility in upstate New York. “By that point I was tired. I was ready to go. It was like, ‘All right, I’ve tried everything else.’ I couldn’t figure it out.”

"One day, the light went on. I finally figured out I was the person that was in my way. It was suddenly obvious..."

And then one afternoon in rehab, after another seemingly endless exercise in self-examination (“They always had us writing shit about our lives, these group sessions”), Jackson was struck by a pang of clarity. “I’d watched all of these other people get plucked out of New York and go to Hollywood or wherever and start their successful runs,” he recalls. “One day, the light went on. I finally figured out I was the person that was in my way. It was suddenly obvious.”

One week after leaving rehab, Jackson was cast in his first major film role — as a crack addict, Gator, in Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever. Jackson smiles at the irony. “I didn’t have to write up any backstory for Gator. I’d lived it.”

In the final scene of Jungle Fever, Gator is shot by the family’s Reverend after he attempts to steal from his mother’s home. “When you’re an addict, you use up all your relationships,” says Jackson. “But once that shit cleared up and I got out my way, I was off. When the Reverend kills me in that movie, he effectively killed the addict that I had been.”

6. Create a market of one

When the nineties arrived, so did Jackson. With addiction behind him, and a raft of distinctive movie roles under his belt, the actor had moved from Broadway outsider to box-office star.

“Casting black actors is still strange for Hollywood,” Jackson said in a 1993 interview. “Denzel gets the offer first. Then Danny Glover, Forest Whitaker and Wesley Snipes. Right now, I’m the next one on the list.” But that would soon change. In 1994, with a single role, the actor put himself suddenly in a category of one. Samuel L. Jackson: accept no substitute.

“It was my deliberate choice to be as different as I possibly could in as many films as I could,” he says. “So I made my face and my hair and my beard my canvas. It was my idea for the wig in Pulp Fiction. Quentin [Tarantino] had actually sent a girl to South Central to buy an afro wig ’cause he was referencing Blaxploitation. But she came back with this jheri curl wig. Quentin was losing it. And I said, ‘Hold on, let’s try it…’”

Jackson’s portrayal of Jules Winnfield in Pulp Fiction put him instantly into the fuggy atmosphere of Che Guevara or Scarface: walk into any university halls to this day and you can bet that a handful of the students inside have the distinctive image of John Travolta and Jackson Blu-tacked to their walls. (“Hell of a thing to wake up to,” Jackson laughs.)

After Pulp Fiction, directors didn’t call Jackson’s agent because Denzel Washington and Wesley Snipes had fallen through. They called up because only Samuel L. Jackson would do. “I haven’t been to an audition in a pretty long time,” he smiles. “Now, people write stuff, they send it, and I read it.”

7. "Take a damn stance!"

The Wednesday after our interview marks the death of Martin Luther King. Jackson’s life had been curiously intertwined with that of the civil rights leader. “I was an usher at the funeral, because he was a Morehouse alumni,” Jackson tells me.

In 2011, Jackson played MLK on stage in The Mountaintop, an account of the doctor’s last night on Earth. There is an activist, near-radical spirit in everything Jackson has done within that coincidental story arc. And it’s one that has been re-stoked in the past few months.

“I have passed through so many significant changes in this country,” Jackson explains. “I grew up in an American apartheid. But there’s a new temperature of fear in this country. When I was at college we were ready for the uprising. To us, the flavour was that violence is as American as apple pie and that change does not come peacefully.

“But now, young people are truly afraid for their future, mainly because they’re being put in a place that they can’t navigate and survive in. It’s a whole new atmosphere that we never had during our revolution. These kids have a fear of being at school and somebody coming in now with a big automatic weapon. The gun debate is a truly American problem. Nobody wants to get hurt, but everybody wants to get angry.”

"I grew up in an American apartheid. But there’s a new temperature of fear in this country..."

“My advice is to take a damn stance,” he says flatly. “The big positive is that young people are starting to realise the power and influence that they do have. Next year they’re going to be the next wave of voters and those old guys that set policy that tell them: ‘You’re children and you can’t tell us what to do.’ It’s like, ‘Yeah, we can.’

“Keep going. Don’t shut up, raise your voice. The advantage these kids have over us when we were in the streets, is where we were on payphones or writing letters to each other, they’ve got something we didn’t have. They’ve got the internet. They’ve got a voice.”

8. Life's a gold course, so start swinging

Today, as he approaches his 72nd year and his fifth decade under lights, Samuel L. Jackson is still improving his game — almost literally, in fact.

“Work’s like golf,” he tells me. “When you’re about to go perform, whatever you do, you’ve got to know the yardage, know which club you need, understand the feeling.” This preparedness comes from the days and weeks and months of sometimes unrewarding and repetitive work that no one will ever see. “But you’ll know it’s there, and you’ll need it. Some days you go out there and there’s a breeze, some days you go out there and there’s moisture, it’s colder so you have to use another club.

“In those situations, do we work harder, or do we just trust what’s happening?” Jackson asks. “For me, you put the club in your hand, trust what you learned, trust what you feel.”

“Golf is a game of personal accomplishment. Just a little ball sitting there waiting for you to move it in a specific direction,” Jackson told James Lipton on Inside the Actors Studio. “If you do it successfully, you get all the credit. If you don’t, you get all the blame. And it takes concentration and relaxation to be good at it.” (The big man plays off about six and has beaten Tiger Woods, by the way, so he ought to know.)

Has Jackson ever had a case of the yips — that famous ailment that befalls golfers when they “get in their own head” and overthink their actions — either on stage or on the course? “That’s when you can’t pull the trigger?” he says, laughing. “Hell, no!”

9. You've never made it

Even now — as a towering institution unto himself — Samuel L. Jackson is worried that this wild ride might come to an end. “My biggest fear is not going to work. I’m still that actor,” he says. “I tell myself that the phone stops ringing for everybody, doesn’t it? I was at dinner last year with Maggie Smith, my agent and Michael Caine.

“Michael was going to another job and I was finishing a job in England, and Maggie had just finished doing Downton.” He giggles. “She said: ‘I don’t have any work.’ And we were like, ‘You’re Maggie Smith!’ But she was scared. We want to work!”

It’s a humbling lesson, and the incurable side-effect of the consummate professional. And Samuel L. Jackson is a goddamned professional — a professional artist, icon, activist, star, role model. “A painter will get up and paint. A writer’s gonna write,” he says, spreading his arms wide and grinning. “I’m Samuel L. Jackson. I’m gon’ act!”

Want more from Hollywood royalty? Here’s an essay on Willem Dafoe’s face…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.