The history of preppy style (and why it's still going strong)

From square-jawed Princeton boys to the Lo Lifes smashing in windows on Madison Avenue, the story of Ivy and prep is the story of modern America

Words: Finlay Renwick

The earliest iteration of the Ivy League look took shape on the cam-pus of Princeton in between the First and Second World Wars. With imposing gothic architecture and high iron gates, located in what was then referred to as “the swamp” of rural New Jersey, its appearance wasn’t dissimilar to that of a British country pile. Its relative isolation allowed its predominantly male, white and Protestant students to experiment with the sporting and high-society clothing popular across the pond: tweed jackets, polo coats and button-down shirts. In her article The Inter-War Years and the Birth of the Ivy Style, Patricia Mears of New York’s Museum at Fashion Institute of Technology wrote, “No other university defined Ivy Style as fervently and as beautifully as Princeton in the 1920s and 1930s. More than the other Ivies, Princeton was the keenest advocate of WASP elitism.”

“The insularity of the campus, the self-regulating and elite nature of the student body, the importance of extra curricular activities such as sports, and the widespread acceptance of sportswear shaped an environment where clothing took on heightened meaning,” adds author and fashion historian Deirdre Clemente. “The strict social hierarchy created and enforced by students for students did much to create a standard style for the public image of the Princeton man. The image was heralded and endorsed by mass-circulated magazines and clothing manufacturers who borrowed the University’s name for everything from shoes to shirt collars.”

Brooks Brothers and J Press, early arbiters of Ivy style, opened stores around Princeton, Yale and Harvard, selling boxy, lightly structured sack suits, unpleated flannel trousers, brushed Shetland knitwear and repp stripe ties. Chipp in New York faded away before being brought back in a zombified form by Rowing Blazers a few years ago. Bass Weejun penny loafers became the de facto shoe of the campus, often worn without socks. Colleges were seen as incubators of impeccable style. A 1933 Apparel Arts article stated: “The American University man is justly famed for representing, as a class, a high standard of excellence impersonal appearance. Much of the secret of this distinction lies in the fact that the first thing the fresh-man learns is the importance of never looking ‘dressed up,’ while always looking well dressed.”

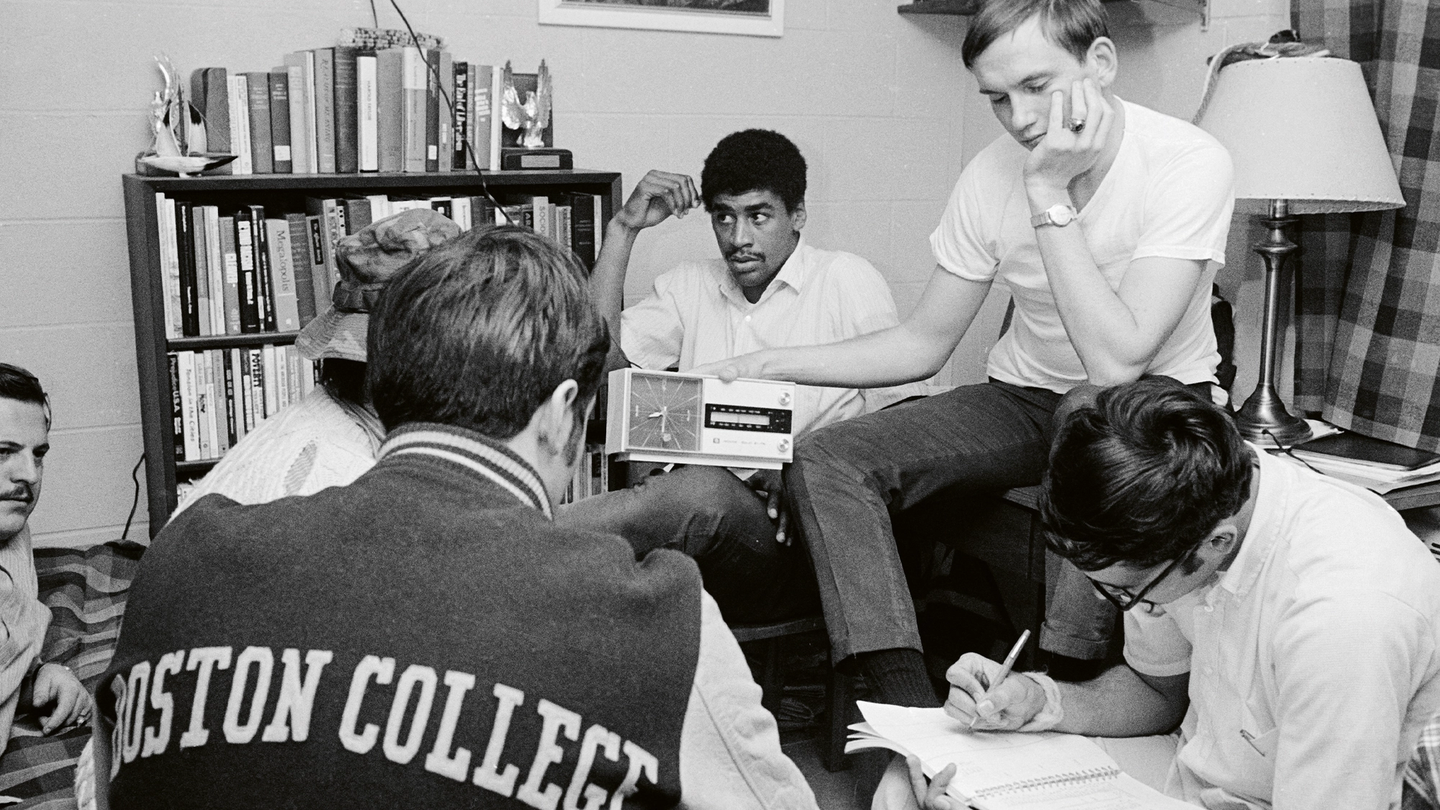

In 1965, a group of style aficionados from Japan travelled to America to capture the Ivy League student in his natural habitat. The group included Toshiyuki Kurosu,Teruyoshi Hayashida, Hajime (Paul) Hasegawa and ShosukeIshizu, who founded the original Japanese Ivy-inspired brand Van Jacket. The result was Take Ivy—a book (a bible in certain circles)and accompanying film that captured vigorous-looking students striding around on campus wearing untucked OCBDs, Bermuda shorts and sweatshirts, Bass Weejuns with no socks and unstructured tweed jackets.

It turns out that the Japanese fantasy of American Ivy was, in large parts, just that. Much of the book and film were staged, as Kurosu noted to writer and Japanese culture expert W David Marx: “Most students acted like they were completely disinterested in fashion, even if they looked like they cared. They didn’t seem proud of being stylish. They would just say to us dismissively, ‘I just came here to study. I don’t care what I wear.’”

As Ivy spread from the cosy campuses of the elite into the wider consciousness, it was utilised in new and interesting ways by demo-graphics that had often been excluded from the conversation. In his 2021 book Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style, Jason Jules discusses how the most notable black jazz musicians, writers and activists of that period were able to put their own twist on Ivy during a time of major social and political upheaval: Miles Davis, Robbie Coltrane, James Baldwin and Malcolm X were, asJules calls it, dressing as an act of “subterfuge”, mixing repp silk ties with denim workwear, or but-ton-down shirts with sunglasses, dressing as equals to their white counterparts. “One of the key goals was to be visible and to challenge the cliches and perceptions of mainstream America. Wearing those clothes was a direct challenge to those negative assumptions.”

You can trace a thread all the way from those early adopters to con-temporary style icons like André 3000 and Tyler, the Creator, famous black men taking something typically seen as ‘white’ (golf or skateboarding, or wearing a pearl necklace) and skewering it with confidence and a sense of humour. Ivy gives way to prep, a term with more loaded connotations (Brooks Brothers famously disliked being referred to as prep).It was brighter and looser than its predecessor, retaining the same aesthetic language, but more open to derision. Where Ivy was a way of living, prep was often seen as costume — the Yuppie-core of Bret Easton Ellis and Wall Street; books like The Official Preppy Handbook, and the satirical 1979 “Are You aPreppie?” poster by Tom Shadyac. One of its lines reads: “Do you dress in a way that attracts women to other men?”

Key items were deck shoes, washed denim, pastel polo shirts, khaki pants, signet rings and navy blazers. “Preppy is postmodern Ivy League,” the author and authority G Bruce Boyer told Ivy Style. “It’s a more conscious thing. Even the jazz guys who played on campuses very consciously copied that look and modified it. And Ralph Lauren made a fetish out of a lot of that stuff.”

Despite starting out in 1967 selling ties out of a drawer in the Empire State Building, Ralph Lauren, born Ralph Lifshitz, has proven to be the one who foresaw and mapped out the modern landscape of lifestyle and what we now see as prep.Brands like Drake’s (full disclosure, they are my employer), Aimé Leon Dore, Thom Browne, P Johnson and Rowing Blazers have all built on the foundations that were set by Ralph. Buy this; wear it here. Ralph the cowboy, Ralph the city slicker, Ralph the family man, Ralph the beaming recipient of an award wearing an immaculate tuxedo.

“Brooks Brothers was the foundation, and I revived it,” Lauren, who started out at the company before founding his eponymous brand, said in a 1985 interview with New York Magazine. “What Brooks Brothers used to be when they were great — that was what I went after, what I love, which is a lifestyle. Men who had a lot of money would go into Brooks Brothers to buy shirts, and say, ‘Give me three white, three blue and three pink,’ and they’d walk out. They’d do it every year, year in and out. They weren’t interested in what was the latest this or the latest that. I recognised a certain mentality and security about them. Working there was like going to an Ivy League school; there was an ‘in-ness’, a quiet ‘in-ness’ about that kind of place.”

From square-jawed Princeton boys to the Lo Lifes smashing in windows on Madison Avenue, the story of Ivy and prep is the story of modern America, a sense of opportunity and constant reinvention. You can be whoever you want to be... as long as you’re wearing the right clothes.

Want more fashion content? Check out the best-dressed men from the 96th Academy Awards

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.