Paris is dead: long live Paris

- Words: Joseph Bullmore

No-one can tell you why the light in Paris is better. I asked two photographer friends who really ought to know, but they gave nothing away beyond a borrowed Gallic shrug. Someone in a bar said it was something to do with the abundance of street foliage and the always vaguely over-cast, hazy conditions, which make perfect ‘diffuse light’ that softens skin tones and seems kinder and calmer, somehow. Another pal said something about the position of the city on the earth’s latitude, and the angle at which the morning and evening light penetrate the Parisian atmosphere, and the scattering of particles and sun rays, which sounded good, as most nonsense does. Gifted amateurs, all. The real truth is that the light in Paris isn’t better, necessarily — it’s the stuff it falls on that’s different.

Reports of Paris’s death have been greatly exaggerated. In recent years, a certain stripe of Parisian has rather enjoyed crying that the city is over, that the romance is gone, that it’s not as it was. They might use phrases like ‘gilded cage.’ They talk about politics and covid and the traffic. They shrug over square footage and brood at a new tension in the air. The arrival of Soho House can’t have helped. You’ll have heard of Paris Syndrome, the psychological snafu where visitors from the East, who have long put the French capital on a shining pedestal, arrive here and realise that it’s just a city — not a movie set nor an aphrodisiac; not a cure for their writer’s block or their marriage. And soon they begin to unravel, lost in a spiral of mundane disappointments. I sometimes wonder if Parisians enforce a similar, low-level syndrome on themselves — always hoping, every time they open their shutters, that the city outside will live up to the promise of some faux golden age, or ring with the intensity it did when they first moved here as a small town chancer. But you need to see it from the outside — arguably with an enforced, pandemic-flavoured hiatus of about three years, say — to tell them the simple truth. They don’t know how good they have it.

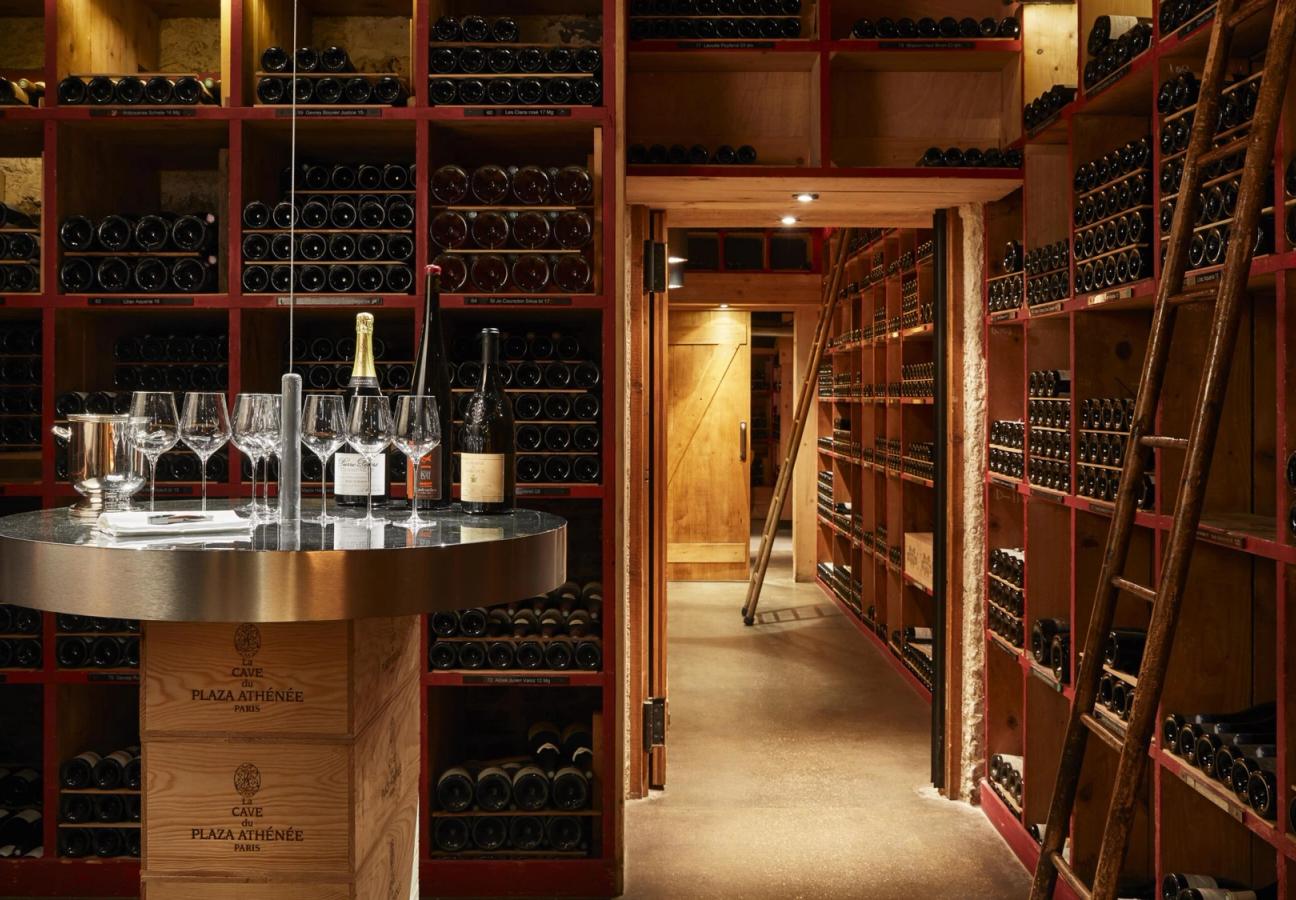

Take the Hotel Plaza Athénée, down near the Champs Elysee. This is Paris as it should be; Paris as it was. My dad used to come in another life, and when I mention I’m dropping by he says a single phrase to me: “the red awnings!”. You can see these from the outside as you drive along the Avenue Montaigne, if you like. But they’re much finer on the inside — a chorus of little red rectangles jutting out from the deep green ivy that coats the golden-stoned courtyard like a cashmere jumper. Every grand dame hotel should have a money shot (the broad, sloping gravel pathway of Hotel du Cap; the symmetrical grottos of Villa d’Este.) And this is the Plaza Athénée’s— the courtyard in bloom and in high contrast, the sky a vivid blue above, the clientele insouciant as ever below. You can see the Eiffel Tower from some of the chi-chi-er suits, which is a nice touch, of course. But the most pleasing views are in the lobby, or down the long, vaulted corridor-dining-room hybrid where the great and good of Paris parade, and the rest of us eat eggs benedict. If it reminds you of a catwalk, then so be it. Plaza Athéneée has always attracted a certain style-conscious crowd since it opened in 1913, and Christian Dior named landmark collections after the hotel.

Not that this is a place of tight-corseted moderation, however. Below the shiny cloche of the all those art deco features and filigreed decadence you’ll find a restaurant of generous gastronomic proportions. Jean Imbert au Plaza Athénée fizzes with energy and inventiveness thanks to its eponymous chef, a brilliant young man with perma-ruffled hair and a playful twinkle in his eye. I’m told there were hushed groans among the city’s boorish gourmands when Imbert took over from Alain Ducasse — they feared change, and distrusted youth, which may or may not be the same thing. But they need not have worried a jot. Imbert’s ingenious menu spans almost all of France’s deep, rich culinary history and pops out happily in the present. (Some recipes remain untouched from 250 years ago, while the decor itself — shorn of the statement Ducasse monochrome — is all Dauphin-esque indulgence and sumptuous silks.) Imbert was recently named one of Vanity Fair’s 50 most important french people and GQ’s Chef of the Year, and he is precisely Paris at its most dynamic — unburdened, apparently, by the past and unbowed by the future.

Then there’s Le Meurice — another fixture in the name-dropper’s canon, and a place once described by Conde Nast Traveller as “the most Parisian hotel ever”. This was the city’s first ‘palace-status hotel’, and it has absorbed two of the city’s most pressing concerns over the decades— art and celebrity. It is perhaps the more sprightly, more rebellious version of Le Crillon or the Ritz — its two stately neighbours. (There is a rather touching and telling story about the elegant greyhound logo which adorns Le Meurice’s literature: it’s based on a stray dog that the hotel workmen fell in love with and adopted in the late 19th century.) Salvador Dalí was a longtime resident here, for example — and the place is fond of a trompe l’oeil or a sudden change of tone. Strolling in off the arrow-straight Rue de Rivoli, for example, and glancing up at Le Meurice’s celestially-high ceilings, you would be forgiven for thinking you’d rolled into the palace of Versailles before things got a little, well, choppy, shall we say. But then you’d notice the clean, modernist lines of the Philippe Starck furnishings, or the clear plastic chairs in the dining room, or the vast, frozen graffiti mirror in the hallway (you can scratch your name into the ice, which slowly heals itself as it melts and re-freezes) — and you’d know you were seeing Paris at its most modern.

Le Meurice has always been a place to let off a little steam. As I listened to rapper Pusha T’s much-acclaimed new album last month — with all its gritty, keyed-up glamour and bombast — I was pleased as punch to hear him name drop the hotel. Many other rambunctious creators have preceded him, of course, and there’s still a chunky dent in a priceless canvas in the Pompadour room from where Picasso fired off a champagne cork at his wedding reception. In ‘Le Dalí’ dining room, the staff feel this spirit right down to their perfectly-polished shows, and tend to facilitate a good time with almost telepathic skill — the chablis topped up at just the right moment; an explosive, exquisite amuse bouche emerging at just the right moment. The controlled, meticulous Haussmann exteriors of Le Meurice may not scream good times and abandon. But they reveal what Paris has always known, what it has always promised, and what it has never really forgotten, despite its recent protests: that there is no pursuit more serious than having a good time.

Read next: 50 hotels every gentleman should visit before he dies