Oh Brothers, where art thou? Charting the demise of Brooks Brothers

As Brooks Brothers folds after 202 years, we lament the death of an American institution

- Words: Harry Shukman

Everyone will remember where they were and what they were doing, just like all those other moments of great American tragedy, when they heard the news. Walking across the fairway, or trotting to the jetty to board the 63 Virtus for an afternoon cruise around the Hamptons — and suddenly the terrible call comes in: “Brooks Brothers has filed for bankruptcy.”

For Wall Street veterans of a certain age, the demise of America’s preppy outfitter would have landed with the force of a body blow. Managing directors and hedge fund bosses will have stood stock still at the 11th hole of the Maidstone in East Hampton, or paused over their glasses of Armand de Brignac at the Edgartown yacht club on Martha’s Vineyard, and shed a tear. And with all the solemnity of a cold parade ground bracing itself for the final notes of the Last Post, they would have spent a minute in silence remembering how Brooks Brothers came into their lives.

Back in the day, one’s relationship with Brooks would have begun with a jaunt to the flagship Madison Avenue store, perhaps on a day trip up from Princeton, to get kitted out for an internship at Goldman Sachs. The inside of a Brooks store was like a Hollywood vision of Oxbridge, a jumble of battered leather trunks, stacks of dusty volumes lining the shelves, threadbare Persian rugs and sepia photographs of turn-of-the-century hockey teams. In short, an imitation of Lord Sebastian Flyte’s undergraduate rooms; Disneyland Christ Church.

This was where generations of masters of the universe came to buy three-button black suits in a Madison fit, generously tailored around the chest and thighs to accommodate the robust American male, a solid red tie with perhaps a floral print for special occasions and a week’s worth of their famous button-down shirts. “Tremendous, just tremendous.”

With what satisfaction would these young men have looked upon their worsted shoulders in the mirror, knowing that the great and the good had once stood in the same spot, admiring the cut of their own jib. After all, Brooks was founded in 1818 by Henry Sands Brooks (placing it almost in the Stone Age by American standards), and had dressed all but four US presidents, with its signature thick overcoats appearing at the inaugurations of Abraham Lincoln and Barack Obama. Clark Gable was married in it. Charles Lindbergh, after completing the first transatlantic flight in 1927, wore one of their suits. Andy Warhol’s entire wardrobe was said to be made up entirely of Brooks. “You must go to Brooks and get some really nice suits,” Amory’s mother tells him in This Side of Paradise. Incidentally, when Brooks Brothers took legal action against Brooks Clothing, a rival operation ripping off its name, that line from F Scott Fitzgerald’s high society tale would prove instrumental. “Brooks” could only have meant “Brooks Brothers”, its lawyers argued, thus winning a civil action in 1949 in a nifty legal manoeuvre that would have surely appealed to the New York boardroom commandos wearing their clothes.

"Retailing has been changing a lot in the last four to five years. When coronavirus came, there was really no way to sustain things."

They say old soldiers never die, but simply fade away — which could account for Brooks Brothers’ unfortunate demise. The coronavirus pandemic decimated sales, with grim prospects ahead given that workers at home dialling in on Zoom are unlikely to need a regent-fit double-breasted plaid suit for £1,400. The same woes have afflicted J. Crew, which has filed for bankruptcy, and on this side of the pond, TM Lewin was reported to have fallen into administration after it shut all of its 66 shops.

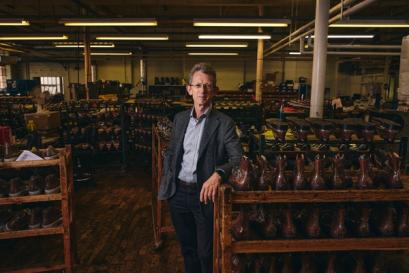

Bad tidings for Brooks, which survived 202 years that included two world wars, various recessions and 9/11. After the terror attack ruined its downtown store, Claudio Del Vecchio, the Italian businessman who owns Brooks, had vowed to reopen “as a matter of principle”, which he did a year to the day later in 2002. But the pandemic was the thread that broke the camel coat’s back.

“Through every era, we had challenges, but we were confident we would be able to manage through them,” Del Vecchio told the Wall Street Journal. “Retailing has been changing a lot in the last four to five years, and we were in the process of adapting to that new environment. When coronavirus came, there was really no way to sustain things.”

New trends in Wall Street style, according to today’s young guns, were equally problematic. The boxy suits and parachute shirts with high collars and stiff cuffs, once beloved by executives, fell out of date after the crash of 2008, in which bankers were seen as pinstriped demons with slicked-back haircuts.

“The financial community has sought to shed that image,” says the anonymous creator of Litquidity, a popular Instagram account for aspiring Manhattan big shots. “And it has also been competing for talent with Silicon Valley, a community that is known for its casual dress with t-shirts, hoodies and Birkenstocks in the workplace.

“Younger financial professionals have embraced a ‘smart’ business casual look that includes fleece vests, stretchy sweatpants that look just like suit pants, and even dress shirts made out of performance fabrics that feel like golf polos. Why feel uncomfortable in stuffy clothing while… meeting with clients that are dressed in quarter-zips and chinos?”

It would seem that today’s rising stars of finance would sooner dress like they’re heading for a gentle day of wine tasting in Napa Valley instead of storming in to snap necks and cash cheques in M&A. Despite its pedigree, Brooks Brothers, most likely worn by Gordon Gekko, couldn’t hold its own against the fashion sense of Mark Zuckerberg.

Time to pour one out then for the Milano fit sharkskin-style suit in navy blue, condemned to gather dust in the walk-in wardrobe of a Murray Hill penthouse for the rest of its days. It will hang next to a stack of multi-stripe slim-fit button-down dress shirts and a flutter of silk ties once purchased with all the possibilities of a fresh morning on Wall Street, when the sun glitters off the glass ziggurats of downtown Manhattan, promising a bonus so big it would be visible from space.

Looking for success stories? Here are the business lessons to learn from Patagonia…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.