Words: Joseph Bullmore

Reports of the death of the media industry, to steal from Mark Twain, have not been greatly exaggerated. (And Twain, while we’re at it, would be colossally screwed in the current creative marketplace.) You may think that you’re reading these words in a magazine, but, in essence, you’re not. This is not so much a publication as a scrap of a life raft (albeit a very handsome scrap, sure, and a very beautifully manned life raft), cast off from some stately old galleon, once captained by great men and women in nice hats with excellent expense accounts, but now dashed and wrecked and left to consult for LVMH.

The ship is gone and we saw the tsunami coming – it was the internet, and it was irresistible and beautiful, even as it was obliterating, and all the entities that have tried cleverly to surf its swell since have survived for a while before inevitably being pulled under – BuzzFeed and Vice, say, with their manic attempts to bail out with scale – while the rest are left to piece together new hopes from the flotsam and jetsam of the boats of before (Newsletters! Coffee table books! Dial-in conference calls! Radio!), and good luck to them, of course, and all who sail in them.

In the meantime, the rest of us must construct painful extended metaphors, like this one, perhaps, in the hopes that their sheer ambition may yet secure one more commission, and then one more – not drowning yet, but waving – and still one more, until, inevitably, with a glug and a sigh, we too go under, or at least try to start a podcast.

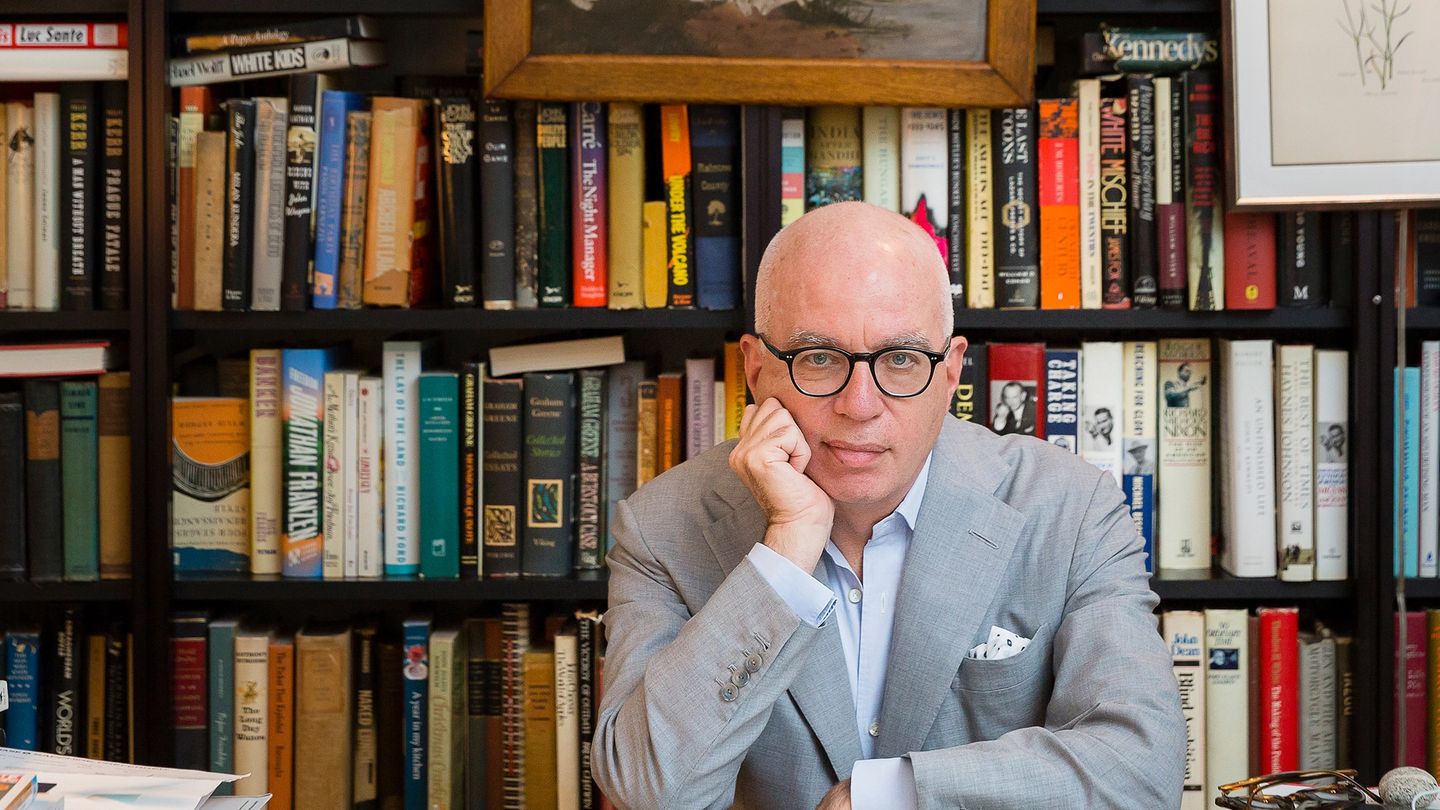

Michael Wolff is a man who has seen it all, several times over. He is a media storm chaser. He has sometimes been in the centre of the storm himself. (“There have been particular times when I became the subject of paparazzi, and that was disconcerting and instructive,” he says.) He worked for the New York Times after college, but got out while he still could, and has written for New York magazine on and off for decades. In the 1990s, he briefly flirted with media mogulery when his start up, Wolff New Media, got sucked up in the dotcom boom. At one point, he was told he was worth $100m. Just a few days later, he was told he was not. The precipitous highs and lows of this process – the general tulip mania of it all; the sense that the adults in the room had wandered out into the traffic – was brilliantly captured in his 1998 book Burn Rate, whose healthy sales helped him make back some of the money (and prestige, perhaps) he had lost when things went crashy.

His subject throughout all of this has been the media, but not in the way that media was once written about, with its academic sniffling and newspaper canteen rumours. More the media as a reflection of everything else; the media as seen through the people it creates and destroys, and the people who do the creating and destroying. Fame, really, is the uniting principle of a lot of Wolff’s writing, and money, too – the two best/worst things in the world, depending who you ask and who’s replying honestly, and also how much coke they’ve had at the time.

On each side of this bargain sit Wolff’s two biggest and most formative subjects: Rupert Murdoch (about whom he has written two books, one of which, The Fall, came out in September, 2023, to much acclaim and Succession-tinged thinkpieces) and Donald Trump (about whom he has written three books, all of which probably made Wolff both rich and famous in their own ways).

Trump, in particular, is the great orange mirror of our age, and a Wolff speciality – a Frankenstein creation of himself and of the industry, someone who seems to have been able to escape the bounds of simple media figure (or, at least, use it in ways heretofore unimaginable) to become something else entirely: that something else being a potentially twice-elected US president.

His other major subjects are collected in one of the most dog-eared books on my shelf: Too Famous, which tracks “the rich, the powerful, the wishful, the notorious, the damned” over 20 years of columns and essays. I experienced vicarious palpitations when I first read it, mainly because the portraits of the people Wolff writes so intimately about – such as Tina Brown, Michael Bloomberg, Alan Rusbridger – are so incisive, so compelling and so often pointed to the emperor’s nakedness.

This kind of candour and clarity of thought is very rare in magazine writing nowadays, and, so, that’s where I began with Wolff, as we chatted over Google Meet, me asking him whether he ever gets a moment of nerves before he hits send on his copy and launches these exquisite grenades into the world, and how he feels about the people he writes about and the way he writes about them. We discussed Succession, obviously; the last days of Jeffrey Epstein; getting rich; not getting rich; the death of Rupert Murdoch – and how Wolff suspected he might well have caused it.

JB: I vaguely interview people. I can’t imagine how it must feel to interview people and write things about them they so clearly don’t want to be written...

MW: With me, it’s a DNA issue; I can’t help myself. And, in addition, I always think I’m writing something positive. I’m always flabbergasted: you didn’t like that?! That’s you!

Do you ever feel nervous before you hit send on a piece?

Never! When I hit send, I think: they’re really gonna like this. I wait for the call saying, “Oh wow, you really captured me.”

Has anyone ever given you a glowing review of your work?

No, good point. I don’t think they ever have.

You’ve spent a lot of time in England, and, in an interview with Piers Morgan, you said you preferred English people to Americans, as English people are less “phoney baloney”...

Journalists and media people in the UK have a somewhat humble, cynical, comical view of what they do – which is the exact opposite in the US, where the view is largely religious. We’re Journalists.... They say this word...

[In the UK] there’s a kind of writing elan or respect or humour. The UK’s thing is that it’s fun to write well. And that has gone from the US view. The death of magazines in the US has meant that all journalism is now a corporate and bureaucratic enterprise, and the only future you have is to, at some point, go and work for the New York Times. So, it’s pretty dismal.

There’s no magazine business. There’s no advertising for magazines, and, functionally, there are no magazines. Whatever the digital landscape is, it exists in a different form. It’s a shadow life.

New York magazine still has a certain glamour, at least on this side of the pond...

It used to be that on Monday morning, anybody who was anybody in the city got the magazine. And I used to be in every issue. So, it was that moment, and you felt it, and it felt great. It was bigger than television. It’s not that incredible sense of everyone reading it at the same moment anymore.

In a broader sense, I’m grateful to the book industry and grateful to Donald Trump for helping me to make this jump. I’m basically writing a book every year, and they all sell rather well. But, because I am the way I am, I always assume this will end tomorrow.

Would you get into the media business now, if you were 40 years younger, say?

My older children are all in the media business in some way, and I think that’s a complicated thing. They’re in the media business probably because I’m in it, and I feel a little guilty about that. On the other hand, what else would you do? I mean – plastics?!

In your [2011 GQ] interview with Piers Morgan, he says you must be obsessed with the Murdochs because you wrote one book about them [2008’s The Man Who Owns the News]. You’ve now written two books about them...

It’s a great story – the story of our time. Seventy years of Murdoch creating the media business all of us are living in. It’s Murdoch’s world, and we’re all just living in it. Or, at least, it has been. Now, for it to come to an end in this, kind of, near-tragic way, you know – in the end, he doesn’t get anything that he wanted, except the money. So, it’s pretty hollow, pretty sad, pretty human. It’s an irresistible story, and if you write about the media business, as I have done for many years, he is the whale.

“I suppose I’m grateful for Donald Trump, who is a media figure, but has now transcended to some greater stage”

What do you think he wants?

He’s after his happy place: the newspaper business, which, practically speaking, does not exist any more, or is just a shadow of its great and powerful self. And, he wants a dynasty, which he’s never going to get because his children can barely speak to each other. And, he wanted to elect the US president, and the president that he ended up electing was Donald Trump, whom he detests.

Illustration: REUTERS/Jane Rosenberg. A court sketch from the fraud trial of Donald Trump, subject of three Wolff books.

Do you get the sense he still thinks he might defy the odds and live to 110, 120?

I don’t. He’s 92 years old – 92 is 92, even for Rupert Murdoch.

Does he ever talk about death to you?

Well, he doesn’t talk to me any more. But, I know many of the people he does talk to, and you have to be pretty courageous to bring up that subject. He’s pretty fragile.

How will you feel when he does die?

One of the last conversations I had with him, in which he was yelling to me about my biography – incredibly angry, and unreasonably so, I felt – I said to him, “Remember that I am going to be the first person that’s called when you depart this vale of tears.” And that stopped him for a second. But only a second.

Do you think those were the last words you’ll say to him?

I appear to have said my last words to him. Although, when I was finishing The Fall, I texted him and said, “I would love to sit down with you.” He replied immediately: “No thank you.”

Will it be a poignant moment for you when he dies?

I suppose it’ll be one of those moments that I’ll go: woah. A couple of weeks ago [late 2023], Andrew Neil called me and said, “I’m hearing that Rupert’s dead.” And, I thought: woah. I said, “Let’s see.” Within five minutes, we go back to each other and realise that had not come to pass. But, I thought: I’ve killed him! I knew it would eventually happen, and I’ve done it!

It’s kind of ludicrous that this 92-year-old man can run two public companies. He’s allowed to do that because he’s Rupert Murdoch and he upholds all his voting shares. But, even with a halfway closer look, you go: wait a minute, this really doesn’t work.

Did you like Succession?

I did like Succession very much. The moments it came alive were the moments when they went as close as they could to actual events, which were events that I wrote about. Having said that, they took that material and made this other story, which, in its own terms, succeeds, in terms of its own internal integrity.

I heard from Jeremy Strong a number of times, and he, in fact, blurbed The Fall, so he appears to have closely read the books.

[Later on, Wolff says: “Succession is interesting because Murdoch is not like that character at all. He is the exact opposite: shy, reticent, inarticulate, conflict-adverse in his real-life person. And, it’s almost like, to compensate for that, he has to create this powerful, aggressive, media empire.”]

One of the most powerful scenes is the death of Logan Roy in the final season. How do you think the Murdoch children might have felt, watching that?

I don’t know. I’m sure they have rationalised that this is not about them, and is far from their experience. On the other hand, they live with this all the time, and Rupert is 92 and this figure in their lives at a level of weight that I can only imagine. It’s pretty daunting and probably oppressive.

In Too Famous you write about some of the big beasts of media. There aren’t that many of them left. Are you running out of people to write about?

I’m grateful that I don’t have to write about the media business any more. I suppose I’m grateful for Donald Trump, who is a media figure but has now transcended to some greater stage. I think the media business is a business that I rode up and rode down. People are unpacking this business and trying to work out if there’s anything that grows up in its stead.

Did any of your subjects really dislike your characterisation of them?

I used to run into Harry Evans, and Harry would always engage me in discussions about Murdoch, and was always very complimentary about my work on Murdoch. And then, he would always add: “You know, my wife [Tina Brown] really hates you.”

I’ve [just] heard that she wrote a review of The Fall, which I have not read because I don’t read reviews, and I’m especially not going to read this one. Apparently it’s a revenge review. And, I thought, when I heard about it: well, I deserve it.

Do you ever regret the things you have written?

I wouldn’t say I ever feel guilty about what I’ve written. When I write something, I write it because I feel it’s good. And, I would hope I don’t write something I’m not really pleased with. But, having said that, I have met people later on and thought: OK, I could write this differently now.

I’m surprised to hear you say you don’t read reviews...

I’m writing close to a book a year, and they’re all kind of newsworthy books, on subjects that people are incredibly passionate about, and it interferes. I could spend too much time thinking about what people said, and it becomes significantly more important to me than it does to anybody else. So, the question in my mind is how to regulate that sense of disproportion.

I had asked Woody Allen about some issue, and someone had said something about him – God knows what, many people have said things about Woody – and he said, “The only way I find out about this kind of stuff is when one of my relatives tells me.” And, I thought: that’s a good answer. Why should this be important to me? If you start to worry about the social-media stuff as well, you just go crazy. So, I’ve extended it now. It doesn’t even occur to me to want to read something [about myself]. It becomes very central to your own thinking. When it’s not central, nobody else cares.

“I wouldn’t say I ever feel guilty about what I’ve written. When I write something, I write it because I feel it’s good”

What interests you about the media business now?

I’m vaguely interested in the discussion about what comes next, and what comes out of this. I see it as intellectually interesting, but not dramatically interesting. I’m not that interested in the technology business. So, again, I’m grateful for Donald Trump. He keeps giving! I think that this is gonna be a year of years.

It strikes me that many of the people you talk to, talk to you because they see you as one of them in some way. I live in the community that they live in, basically. I think we tend to know the same people, and we’re relatively the same age, so I think that there is something familiar. I came out of an age of journalism when the value was to be inside. Now, I think the value is to be nose pressed to the window, and not be a part of what you’re writing about. To me, the other way is more interesting...

Is there anything you have learned from these people – the Michael Bloombergs of the world, say – that has been useful in your own career, perhaps; in making your own fortune?

No, since I have not made a fortune! All of these people are totally interesting people, which is why I’ve stood there and interviewed them.

You’ve said before that you’ve tried, on several occasions, to “get rich beyond your wildest dreams”, but never succeeded. How important is that to you?

Apparently being rich is not that important to me. I think you get rich if it is important to you, and that’s your obsession. I was always interested in how you make money, and who makes money, and what makes success. But, I’ve come to the suspicion that I may well be lazy.

You came very close to being rich with your media startup...

I did. I had all these bankers, and we went out to the west coast to do this deal. It was all apparently coming together. I remember we were coming back, and we were on a redeye, and I had paid for every single seat in first class. I was sitting with my primary banker – we had gone to college together – and he tried to say, “You should give a building to the school we went to. You’re about to be worth $100m” – I should point out that was when $100m was a lot of money. And, I didn’t question this at all.

I got home at probably 6am. I woke my wife up and said, “We’re going to probably take $100m out of this deal.” And I could still remember the look on her face. It was not even incredulity. It was: this is what you’re going to wake me for?

She thought you were deluded?

Yes, clearly. And, it turned out that I was completely deluded. Within the course of a few weeks, whatever the elements were that had to come together and seemed to have aligned – they seemed, now, to have come unaligned, as so often happens. Then, I remember saying to this banker, “Well, how much am I worth now?” I remember the silence, the absolute silence. And that was about it.

What does something like that do to your ego, to your psyche?

You just have to figure out how you’re going to make a living. I’ve got children to support. It wasn’t that long after that until it literally all came tumbling down and I was thrown out of the country. I had the experience in full, and it was over. And I thought: there’s only one thing I can do now. And that was to write about it. As it turns out, I made more money writing about it than I ever made in the technology business.

What do you think you would have done had the deal gone through?

I don’t know what I would have done. I never knew what I was doing anyway, so I can’t predict what I would have done. I really knew nothing about this. It was just finding yourself in this situation.

Would you want to be as rich as a Murdoch heir? [The Murdoch children each got a $2bn windfall following the sale of 21st Century Fox to Disney, in 2018.]

It’s almost impossible to imagine what that would be like and what it might do to you. The only thing you can say is that it would do something profound to you. You would not be you if you had $2bn in your pocket – $2bn is an interesting amount of money. It’s not $100m, it’s $2bn. You could never dispose of it, spend it; not have it being the thing that is most alive in your life. Without doing anything, it’s making you $200m a year. You cannot rationalise this. But, I’ve aged out of this. I can no longer become a rich man, I think – too old to be rich. The rich are different from you or I...

One of the most remarkable bits in Too Famous is the final essay on Jeffrey Epstein. A question you’re asked a lot is how that access was gained. You don’t talk about that, or make it clear how you got what you got. Are there any particular reasons?

It’s a very difficult subject. It’s not a subject that’s very easily explained. Why one is writing about the subject is not very easily explained. I wrote that some time ago and I thought: this is good. This is seeing something that nobody else has seen and expressed. From a writerly point of view, I think I was doing something noteworthy. From a point of view of understanding this character and these events, this was pretty extraordinary. And I thought: I don’t want to publish this. I don’t want to be in the middle of this.

New York magazine really wanted this and wanted to do a whole issue about it. I debated it and debated it. My wife said, “No, do not do this.” My agent said, “You don’t want to do this.”

I was preparing this book, which was a collection of a lot of old things, and thought: I’ll put this in the book, and it’ll be safe here in a way that it won’t be if it was online. And, the truth about books is, for better or worse, that no one reads them. I have no doubt this is the most insightful and most potentially inflammatory thing written about Jeffrey Epstein, and no one has read it except you. And I am grateful for that. Usually, as a writer, you want as many people to have read it as possible, but not in this case.

In truth, it really presents this in a more complicated way than anyone else was prepared to write about. But, then, the fact that it is not available online and not linkable – that’s a structural aspect of this which makes me think: this is safe here. I got to do what I wanted to do, without the downside.

In terms of writing, what are you most proud of?

I think the Trump stuff is important. Nobody knew exactly how to think about Donald Trump until I proposed this way to think about him. And, I think, that has become the standard way.

We spoke about what Rupert Murdoch really wants. What do you really want?

I just want to be able to keep writing the paragraphs. It’s literally the only thing. Every time anyone pays me enough money to keep going, I think: that’s wonderful.

It feels like you’re going to have a lot more to write about in 2024...

I feel that this story [Trump’s election] turns out to be bigger, more profound, more complicated, more terrifying, more indecipherable than anyone ever thought. From the beginning, one always felt this is going to end badly; this is going to be a trainwreck that hits the wall. And one still feels that, except the wall seems to recede ever further. He could become the president of the US again. This is not pie in the sky. This is not if everything goes wrong. This is a very, very real possibility.

Michael Wolff on…

The Guardian

I’ve always been fond of the Guardian, but I think it is tragically full of shit. The [Edward] Snowden thing was crazy and I don’t think it’s ever recovered. It became this target marketing confection – we know who we’re writing for and we’re going to give you that – which I regret.

Piers Morgan

I think Piers is incredibly talented. I prefer Piers in print rather than on television, but he’s awfully good at this, so I’m very interested to see what he becomes.

Buzzfeed

The whole technology journalism world has, so far, just been about: are you clear-eyed enough to understand your moment, because your moment will pass. Politico understood it. Axios understood. Those guys made money on this. BuzzFeed didn’t understand, and BuzzFeed failed to make money.

Boris Johnson

I can’t believe that there isn’t a ‘next’ for him. I know that everyone in the UK has intense – and often negative – feelings about Boris, and I still have positive feelings. Because I’m outside of it, I have little interest in the politics, per se, and a great deal of interest in the personality.

This feature was taken from Gentleman’s Journal’s Winter 2023 issue. Read more about it here.

Want more long-reads? We examine Miami's development into one of the most important cities in the Americas…