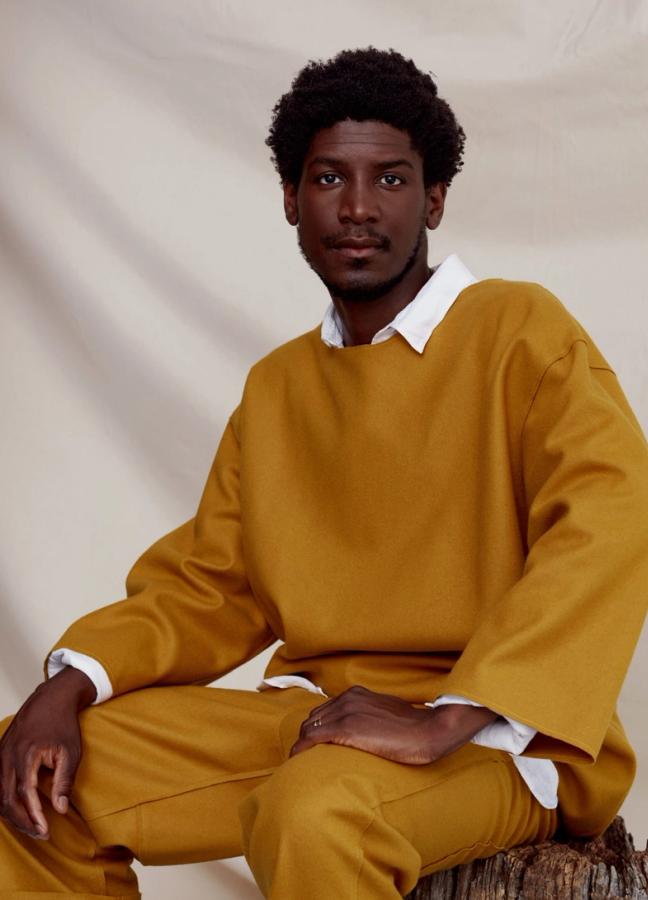

Labrinth — you have been missed

Through fame, writer's block, creative confusion and commercial temptation, Labrinth’s second album has been seven tricky years in the making. Now he’s back — and more buoyant than ever.

Words: Joseph Bullmore

I first heard the song Earthquake in the backseat of Rob Luff’s Citroen C3 outside the Durham University Library, which must have been precisely the way Labrinth always hoped it would be heard. There’s a chord sequence in the verse, and I’d sing it to you if I could, that made me turn to George Simkin (he was in charge of the aux cable at the time, you see) and say “what the hell is this?” I meant it in a good way, of course.

“What you’re hearing there is a scale called the phrygian,” Labrinth explains to me, ten years later, in a coffee shop in Kings Cross. “That bit goes from a straight up relative minor to a harmonic minor, and that’s where it gets you,” he says. “What I enjoy about it is that it feels a little bit drunk. As humans we’re so used to the major scale — that’s our status quo, that’s our mainstream. And so as soon as someone goes a little bit left, our ears go ‘woah!’”

Quite right. Actually, Going a Little Bit Left could be the name of Labrinth’s memoir. The producer emerged in the early 2010s as a precocious hit machine. You remember Pass Out, which he wrote with Tinie Tempah, or Let the Sun Shine, or Beneath Your Beautiful, which took him to number one with Emeli Sande. That was the status quo back then — the new mainstream. The sound spawned a thousand regional nightclub-level imitators, and Labrinth’s echo — harmonic and infectious — seemed to bounce across every pop subgenre. But in the years since he’s been on the march — travelling slowly and steadily a little bit left.

“You have a choice,” Labrinth says. “Do you want your label to think: that’s the fucking man, that’s the number one artist. We sold ten million records: it was shit music, but it was ten million records. Sometimes that becomes an ambition — to have that peripheral validation. And you have to also think: you have a kid now, you have a wife.

“Or do you want to be yourself?” he says. “From 27 to 30, I started to feel that something was going on. Some transition was happening, and I started to become more aware of what I actually want to say, what I want to do in the world. I don’t know where it came from, but it was like my brain got in connection with my soul and my heart at one point, and it was like: ‘okay.’”

The resulting album, this autumn’s Imagination & the Misfit Kid, is a triumph of the space to the left. At some moments it is painfully honest; at others, barnstorming and confident. Often it’s arrested with flashes of extreme prettiness. You would never guess that, in its various forms, it spent seven years in development hell.

Labrinth explains how fame, and commercial interests, began to get in the way. “It’s like being a toddler and getting all the attention I never got,” he laughs. “You’re the super toddler. You’re the number one toddler. You get used to it, and then when that dissipates you want it again. You can become very obsessed with that, and then you stop making music. Then it means you’re writing for a reaction and not for a purpose.”

“Life got fucking crazy, and with the last album, nothing was going right. My team broke down, my relationship wasn’t in a good place. It was one of those moments where life says: I’m throwing you turds, bro. And you keep going: ‘why do I keep stepping in shit? Someone come and clean this up!’

“And then I said to myself — you know what, I’m just going to go with this, and see where it takes me. And eventually there was clarity. Because I stopped fighting the stream, it took me where I was supposed to go. The constant thing was to have faith in the process, and let go. It’s the same with martial arts. Chi is flow. You can’t fight if you stiffen up your body. You have to harness energy instead of trying to control it. You’re planting the seeds but you can’t control how the flower grows.”

This flower grows in several directions at once — there are space age moments, moments humming with the deep south, moments beamed apparently from a Hanoverian prince’s chamber orchestra. A string section in the final track was recorded in an oak room to achieve the resonant warmth. Blessed is sung through Herbie Hancock’s very own vocoder. There’s a line in the The Producer where Labrinth broods: “Ozwald, Versace, Vivienne, you get the message/ I design them beats like Alexander thread them dresses.” This is song making as high fashion — textural, extravagant, showmanlike.

“There’s a link there,” Labrinth explains. “You can take the worst fabric, and with the right taste you can make it look incredible. Taste is a massive thing in music creation. It feels like designers are producers. Even the way Alexander McQueen envisaged a show…

“When I speak to Kanye West and Diplo, they remind me of someone like Alessandro Michele at Gucci — they take all these different elements and they can see everything at once. And when I saw Kanye’s set up, I could see why he’d gone into fashion. They’re both very good at getting the right developers together. They’re visionaries, and that’s what’s incredible about them.”

Labrinth, on the other hand, seems as much a cosmic satellite dish as a visionary. During our conversation he hums little stretches of uncomposed synth sequences, and taps imagined piano melodies on the table top. “I can hear it all everywhere! I have two studios set up at my house, so if I’m working on two ideas, I can work on them at the same time,” he says. “It keeps me stimulated, because I hear music everywhere. It’s like being tuned into universal pirate radio!” It is lovely, for the duration of Imagination & the Misfit Kid, to tune in with him.

Now read this: words of wisdom from another national treasure, Bill Nighy.