“L.A. was the flame — and I was the moth”: Artist Russell Young on the dark side of fame

Inside the Yorkshire-born artist's latest show with Maddox Gallery, 'Glamour Game': a beautiful skewer of the American Dream

- Words: Joseph Bullmore

When Russell Young was eight years old, on a grey, wet evening in Yorkshire, he found himself watching a television show in which someone-or-other was being interviewed at their home in California. California! What was this place? The name, the sunlight, the chest hair, the pose and poise, cheek and chic… Then and there, Young promised himself that he too would one day live in the Sunshine State, wherever it was — and that he too would have a palm tree and a swimming pool in his backyard. (Young, who now lives in Santa Barbara, made good on the promise, of course.)

But it wasn’t just the temperate climate or permanent golden hour that attracted the artist to some far flung land. It was the people that inhabited it, and the world they had created for themselves. This was the Twentieth Century at its glistening creative peak; the 1960s at its most alive and alluring — a vital, kaleidoscopic confluence of Hollywood glamour, post-war wealth, hippyish idealism, and the sexual freedom of rock’n’roll. It was a prelapsarian moment before the death of Sharon Tate or the racist murders at San Francisco’s Altamont festival — an era of titanic shifts and huge personalities that, for all its fragility and ephemerality, has echoed through Western culture ever since. And it’s an era, like those childhood palm trees and that imagined swimming pool, that Russell Young seems bound constantly to return to.

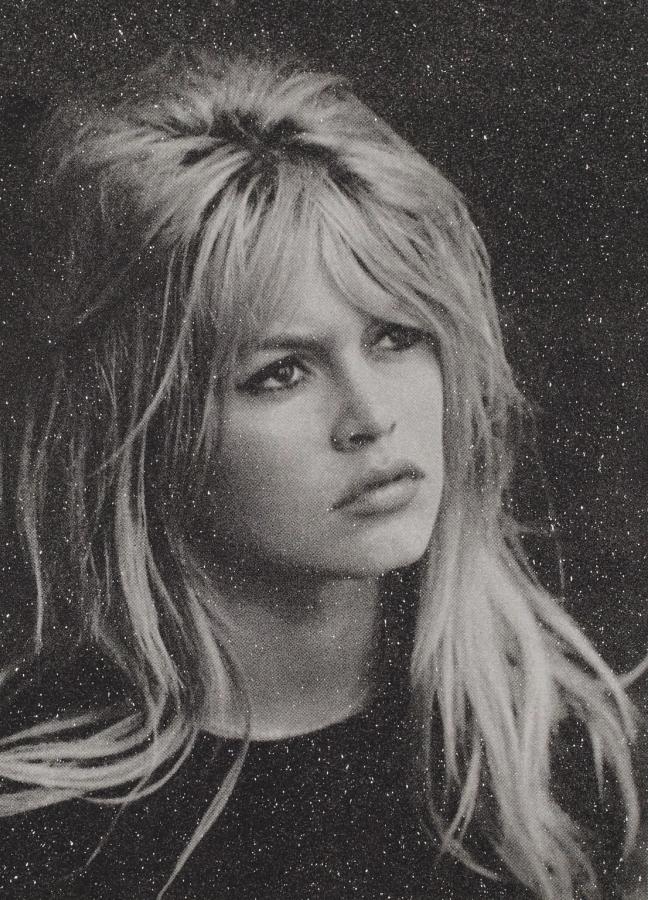

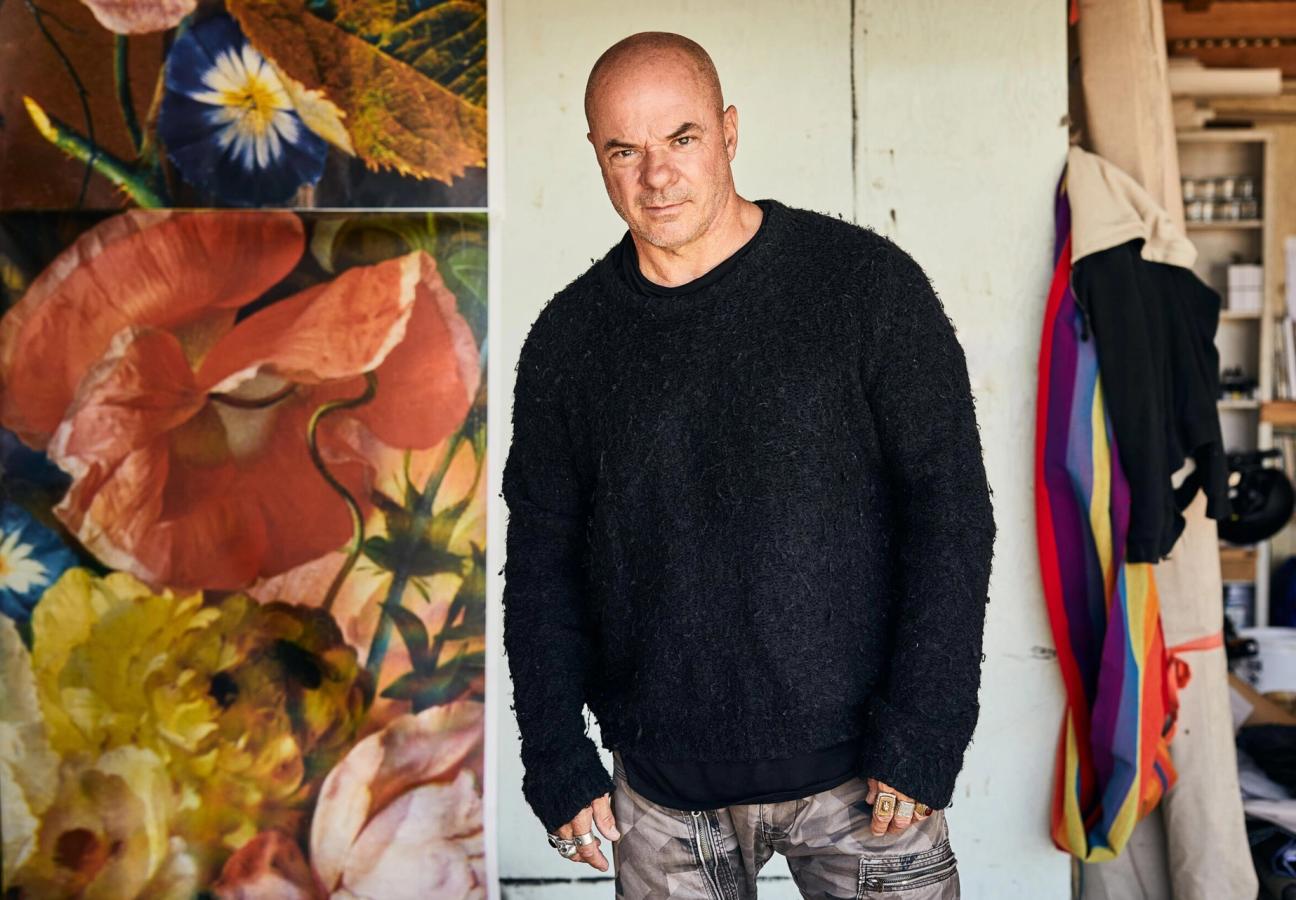

Young is an artist whose take on pop culture is adored by pop culture itself. Bold-face names as diverse as Elizabeth Taylor, Kanye West, Kate Moss, Idris Elba, Brad Pitt and Barack Obama are avid collectors — and they may see in Young’s shimmering works, perhaps, a slight reflection or distant echo of themselves. The artist is most famous for his big, bold-coloured prints of ill-fated celebrities like Sid Vicious and Marilyn Monroe — figures for whom fame and shame were intimately intertwined — which he textures with actual diamond dust. It is stardust made real, and a neat encapsulation of Young’s enduring themes: glittering and yet abrasive; perfect and yet fragmented.

Maddox Gallery Artistic Director Maeve Doyle

Born in York in 1959, Young’s first creative breakthroughs came as a photographer. He shot iconic album cover art and portraiture for the likes of George Michael, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen and and Morrissey — pictures that held an intimacy and fragility even while they put their subjects on some impossible pedestal. Decades later, it’s that intimacy and sense of proximity that still enthrals Young’s acolytes and collectors. Maeve Doyle, the Artistic Director at Maddox Gallery — whose new exhibition with Young at Maddox Gstaad runs from now until February 7th — remembers the first time she saw the work ‘Marilyn Crying’. “It made me wonder when the image was taken and question the context to her life story at the time,” Doyle says. “It goes back to how she was hounded by the press, and really when we think about it, we are still hounding her. And as I look at ‘Marilyn Crying’ today, I want to know why and what was happening to her at the time. It really struck a chord with me.”

Just as powerful, however, is the sense of critique inherent in the works — what Young has called a “a reaction to my former career, where I got paid money to make people seem better than they were.” In 2003, Young produced Pig Portraits, his first series of what he deemed ‘anti-celebrity headshots’ — famous mug-shots and moments of public disgrace, recast and reimagined in bright, primary colours and chiaroscuro moodiness. But even these developed an odd power and sheen of their own — fame still shining through among the infamy, or perhaps even because of it. (“I think they look better than they do in some of the sessions,” Young says, comparing his mugshots with his studio works.)

"The spark was watching movies with my father..."

Now those various tensions — attraction and repulsion; glitz and gore; fame and shame — are brought to life in The Glamour Game, Young’s newest exhibition on his eternal themes. In some ways, they put Young himself closer to the centre of things, and dwell on his own seduction by fame and by Los Angeles, its spiritual playground. (“L.A. was the flame and I was the moth,” Young says of his own story arc.)

In many ways, it is a nostalgic collection; a series of indelible, definitive portraits of the religious icons of the twentieth century, rendered with love. They’re figures who now seem all the more richer, clearer and purer when viewed from the skittering, fragmented, rushed lifestyle of the Instagram age. “The spark,” Young says, “was watching movies with my father, and falling in love with Marilyn, with Steve McQueen — whoever it was in this idealised version of America.”

Doyle finds a similar wistful nostalgia in an earlier print of Jackie Kennedy. “My family are Irish immigrants who moved to Canada,” says Doyle. “And for the longest time I thought I remembered where I was when John F Kennedy died — but in fact I wasn’t even born! It was such a huge moment in my culture and upbringing, I just felt like I was there.”

“We don’t know, but the image might have been taken minutes before the assassination of JFK, and you have to remember that it was the Camelot years when everything seemed perfect.” Until, in a bang and a whimper, everything changed.

Nostalgia, of course, can be overripe to the point of rot. It’s not just JFK. Grace Kelly, Elvis Presley, and Marilyn Monroe: once sirens of the American Dream, each died trying to service or escape it. The diamond dust lends texture in every sense. Young’s silk-screen prints, with their glittering, star-like depths, dare us to look not just at them but into them — at “the surface, and the stuff underneath,” Young says.

Though the pieces are heavily retrospective, they unmistakably call to mind today’s very own ‘Glamour Game’ — a celebrity class that has been superficially democratised but largely cheapened; an America that refutes the American Dream even as it tries desperately to re-enact it. “A lot of people who were around in Russell’s oeuvre believed that if you worked hard, you could build a better life for yourself: Muhammed Ali, Marlon Brando, Elvis, for example,” says Doyle. “I think the American Dream is sadly a nightmare now, and Russell knows it.”

This puts Young firmly in the tradition of Andy Warhol, of course: commodifying and appropriating famous faces as tools of social critique. The Glamour Game is a beguiling collection — pretty, beautiful, richly coloured and dazzling; but at the same time sad, wistful, uncertain of both the future and the past. The pieces are perfection layered on perfection — beautiful portraits rendered beautifully, not least thanks to their liberal sprinkling of diamond dust. But in their perfect unrealness they remind us of the fickleness of fame and fortune — and that dreams are simply the cousins of nightmares.

RUSSELL YOUNG: THE GLAMOUR GAME runs at Maddox Gallery Gstaad, 17th December ’22 — 7th February ‘23

Read next: Chaumeton the Chameleon: Maddox Gallery’s latest star wants you to question your artistic taste