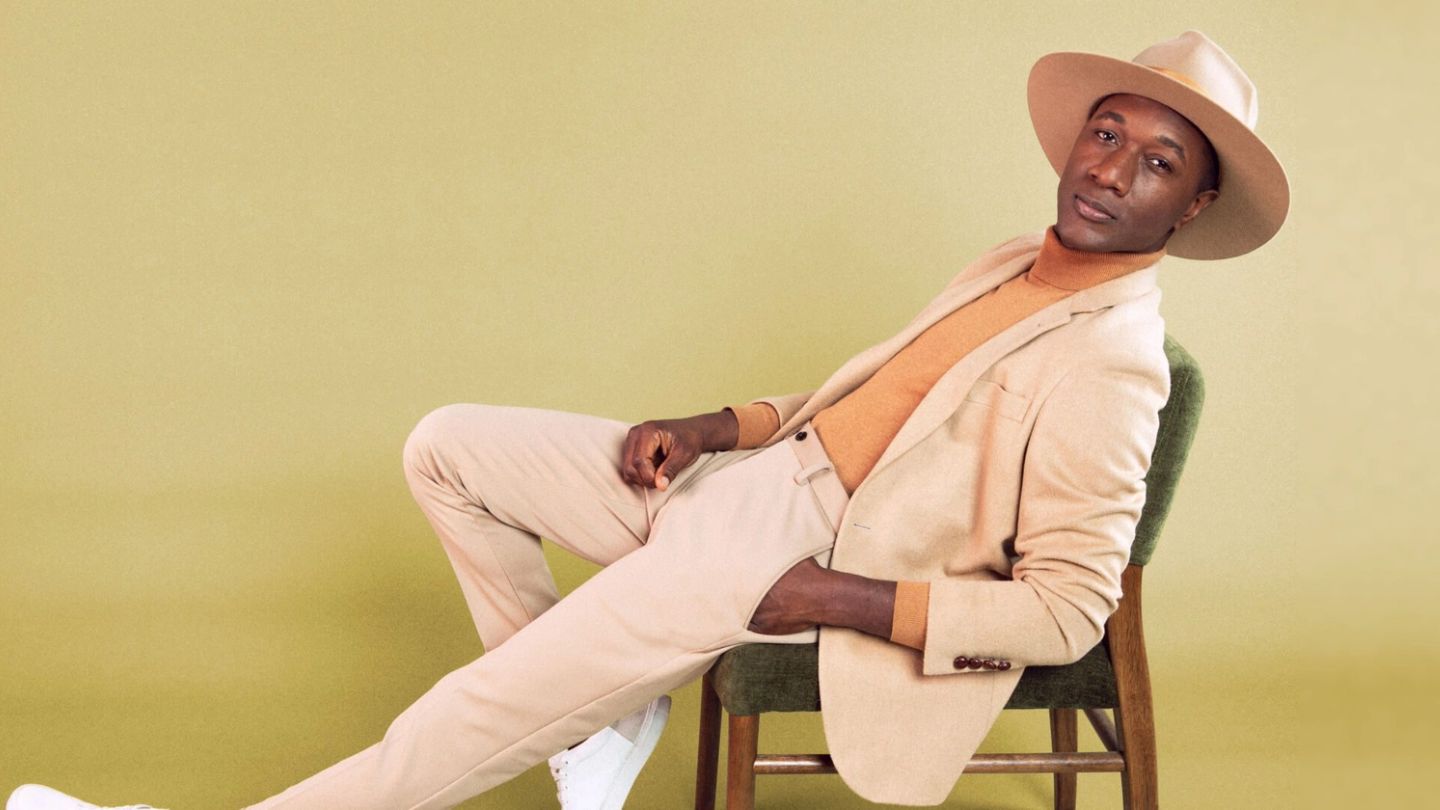

“It’s all love!”: Aloe Blacc on his accidental career

"Whatever you do without making money, that’s what you should think about doing for a job."

Words: Joseph Bullmore

“Serendipity sits on my porch,” says Aloe Blacc. “I walk outside my house and I trip on it every day.” Well, can you really blame it? If I were one of the great cosmic forces of positivity and fortune, I can think of a lot worse places to hang out than in the general vicinity of Aloe Blacc. The soul singer is a human silver lining — a naturally occurring source of optimism. (Probably has a lovely porch, too.)

When he speaks, he has the lilt and composure of a man who arrived at fame a little later in life. He was 30 when I Need A Dollar became an international hit (closely followed by the suddenly unavoidable Wake Me Up with Avicii, which soon went to number one in 109 countries). Before that, Aloe was about to go back into education and study for a PhD. He had been laid off from his job at Ernst & Young, the professional services firm, a few years earlier, and was living in a squat with four other musicians. “Music for me was a hobby. It was never meant to be a career.”

But serendipity, lounging on the porch, had other plans. For two or three summers — those of my university career, if I remember rightly — Aloe Blacc was everywhere. There has been a steady flow of hits ever since (I’m particularly fond of The Man from 2014), and constant splashes and echoes across culture (Aloe writes songs that can sell Japanese lager at one moment, and play out an emotional season finale the next). His new album, All Love Everything, is a tonic for our times. It wasn’t written with 2020 in mind (it would be gently insane to take such a year head on), but it has the buoyancy and light to see us home. “It’s the idea of painting love across everything that we do,” he says.

JB: Aloe — your music and your outlook are so famously positive and optimistic. It’s been one hell of a year. Can you give us some reasons to be cheerful?

AB: In any particular year there are going to be struggles and obstacles. For some people more than others — and for some people constantly. Growing up as the son of immigrants I was able to see that poverty doesn’t mean you can’t live a fulfilled and wonderful life. I use that as an analogy and expand it to other circumstances. Everything is not ideal. But you can still find a way to enjoy life. To find a silver lining in the crowds.

If you are healthy and alive, you should rejoice. And I think we can be optimistic that there will be a transformation in how our health systems work, and about how we engage in public. We are realising that we are all really responsible for each other. Some people are bucking against that. But natural selection will find them. And determine who is right and who is wrong.

How has it been for you creatively, this period?

I’ve been thinking about character — who I am as a person in public, to my fans and to the world at large — and about the relationship between music artistry to film and television artistry. What I present is an honest representation of who I am as Aloe Blacc. But because of this pandemic — with the inability to travel, and perform, and present my music — I’ve been much more online. So the idea of virtual artistry came to mind. So I’m thinking about different characters I may want to develop, who may not necessarily be Aloe Blacc. Aloe Blacc is the down home, folky, soul singer. But I might create another avatar around that.

You have a degree in psychological linguistics. Do you apply those principles in your songwriting?

I didn’t go into a formal occupation, where I could use my degrees in an academic sense. But as a performer and entertainer, there’s a lot of communication going on, and a lot of analysis into how to use language to affect people in a positive way.

Do your songs start with a word or a phrase and then develop from that?

In my daily movements I’m coming up with lyrics, phrases, words, couplets. I jot them down and keep them for later use. And when I sit down to write a song, I can refer back to these ideas. Sometimes they are disparate ideas that I’ve put together; sometimes they are one idea that I expand open. Wake Me Up was a bit like that — it was a few different couplets that had nothing to do with each other, but that felt really good when put together.

How did that song change your life and career?

Wake Me Up gave me the ability to be that much more visible to the music industry. Working with Avicii was a huge opportunity for me to engage in the dance music genre, which was the largest at the time. But also to expand my voice to a plethora of audiences. People who don’t really care about music, even — they just take it as it comes. All these kinds of people were finding my voice. And then my voice became palatable to the television and film industry, to the point that they have been constantly requesting songs for commercials and television shows. So it changed my life in a major way.

Have you ever turned down a brand who wanted to use your music in a commercial?

At one point Walmart wanted to use The Man for an insane amount of money. And the record company was really upset that I didn’t want to do it. But Walmart hasn’t modified their procedures around background checks for people who purchase weapons. In the United States we have a huge issue with mass murders, and the ease of purchasing and procuring assault rifles and other types of weapons.

What was the moment when you realised music was something you wanted to create, and be a part of?

I had already been writing rap lyrics from the age of nine. But it was just something I did for fun — my diary. When I turned 15, I met a local DJ and producer named Exile, and we started a group named Emanon — ‘No name’, backwards. It was named after a Dizzy Gillespie song, who was famous for playing the trumpet. And trumpet was the first instrument I played.

At high school I decided I was going to get into music. I wasn’t going to play sports or video games. I wasn’t going to get into drugs or drinking. I’m just going to make these songs, after school and on the weekend. And that’s what I did — every day, all the time, even through college and into the first years of my corporate life. Eventually I got my 10,000 hours in.

Are you a big believer in that principle?

I feel like it’s about passion. Whatever you do without making money, that’s what you should think about as a career. I was making music without making money. One of my big suggestions and pieces of advice for young people is, while they are in middle school, they should start engaging in something that they love so much. With one caveat: you can’t be a passive observer or a recipient of someone else’s creativity. You have to be an active participant, and you have to become the creator. Once you become complacent in receiving someone else’s creativity and accepting whatever’s on the shelf, you are a consumer, not a producer. You probably will be a good employee. But you probably won’t be a good entrepreneur, or producer, or developer. This is your chance, at this age, to develop the skill to do that.

There’s no issue with being an employee. That’s fine. Even I was an employee at one point. But what I’m getting at is this: if you have the time, and you have the passion, focus on creating whatever you want to create. It could be coding. It could be music. It could be basket weaving. But you should develop, you should create, you should be the producer.

What were you like as an employee? You worked at Ernst & Young…

I had high endurance. I was focused. I had high contribution. But it just wasn’t a passion. I found early in life that I could probably perform well on most things, and I could trick myself into thinking I like them. But you have to make that differentiation, and realise: just because I’m good at this, doesn’t mean I should be doing this.

There are people who can sing better than me. Probably people who can write better songs than me. And there are people who can perform better than me. But when I put together my aptitude in each of these verticals, it’s a special and unique thing. It just ends up working. I don’t want to take it for granted, and I recognise that there’s a value in what I do now. I realised I wasn’t going to be the best employee. And I didn’t very much like being subordinate to anyone. In short, I’m lucky that I got laid off, and that I was able to pursue my childhood passion.

Would it have mattered to you if you had never had mainstream success and recognition?

At a young age, I never equated fame and celebrity with success in music. Before I came up with I Need a Dollar, and released that album, I was already planning on going back into education and getting a PhD. Music for me was a hobby. It was never meant to be a career.

And you wrote I Need a Dollar when you were living in a squat…

It was a house rented by five musicians. In that sense it was a squat. But it was a very artistic environment. Very vibrant. Always music. Always visual art. It was just a good place to be, to be creative.

Do you get your inspiration from others around you in that way?

It may not be direct. But it’s about sitting in the same water. Being in the same airspace as creative people — it just gives you license. There’s no judgement.

You had a five year plan to become a millionaire when you were younger…

Yes — it took longer! But I had a plan. And though it didn’t work out the way I expected it to, the dream made the most sense. The dream of becoming a millionaire was the goal. I thought I could reverse engineer it, and work out how much I’d need to make each year to get there. But it was just an idea. I thought, “Let me see what I can do.” But I wasn’t thinking that it was music that would get me there. I thought it would be some other entrepreneurial endeavour; some hustle.

Are you a great planner in that way?

I’ve only ever gone with the flow. And somehow the flow goes with me. This ride’s going to end soon. And the gig will be up. But serendipity sits on my porch — I walk outside my house and I trip on it every day. So because of that, I feel like I have to pay things forward, and I’m always trying to add something positive to the world.

Do you have impostor syndrome ever?

I’ve had impostor syndrome. I feel it. You feel it when you text a celebrity in your phone, and then they don’t text you back. And you think: “maybe I’m not one of them!” But so be it. It’s a charmed life that I lead. And it feels like it will be self-perpetuating. I’m at a status where I know the minimum amount of work I have to do in order to maintain this. And if I want to do anything more, it’s the icing on the cake.

But the one thing I’d love to do is give more — making more of a difference in the charity and activist space. A lot of that has to do with making more money, and I don’t think music is going to get me there. So I think I need another five-year-plan for a billion dollars. And whether or not that plan works, maybe I’ll trip on serendipity again.

Your new album is called All Love Everything. What’s the origin of the title?

It’s sort of a play on words. In my circles, when we say everything’s cool, we can say “it’s all love.” Or when we say that we have an affinity for someone, we say “it’s all love.” And then the concept of making dramatic, positive transformation comes with compassion. Finding a way to love everything. Humanity, the animal kingdom, nature, what you do. So it’s a combination of two phrases.

So All Love Everything sounds awkward. But it’s the idea of painting love across everything that we do.

Is music more important than ever in a year like 2020 which is so politically-charged? And are the charts as political as they were in, say, the 1960s?

Oh no. Definitely not. The music industry has completely co-opted the message. And in order for them to be any kind of activism message, we’re going to need a revolution within the music industry itself.

What have been the most interesting reactions to the album?

There’s a song called Harvard, and I was writing it with Sam Hollander. There is a lyric where I mention a character I’m speaking to, who has a child with special needs. And that’s when, in the middle of the song-writing session, Sam confided that he had a child that had special needs. Maybe the atmosphere in the room fed that information to me, if we want to get metaphysical about it. It was a deep moment that resonated with me. There are real lives that these stories reflect and will impact.

Aloe Blacc’s new album, All Love Everything, is out on October 2nd.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.