Words: Eleanor Halls

If you walk up Knightsbridge towards Kensington Palace and stop opposite the Bulgari store, the sweet smell of hay and horses wafts over a neighbouring wall. You aren’t imagining it – you’re near the gates of the British Army’s most unusual regiment. This is Hyde Park Barracks, home to the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment.

Even if you don’t know their name, you’ve seen the cavalry if you’ve ever walked down Whitehall. They’re the chaps sitting on horseback in the sentry boxes outside Horse Guards Parade, while tourists snap selfies in front of them. They are men of extreme patience.

HCMR is part of the Household Division, which otherwise comprises the five foot guard regiments – the Grenadier, Coldstream, Scots, Irish and Welsh Guards – and whose colours are blue-red-blue.

Within the cavalry, there are two further regiments, the Life Guards – who were originally formed in 1660 from 80 of Charles II’s supporters – and the Blues and Royals, formed in 1969 after the merging of the Royal Horse Guards (Blues) and the 1st Dragoons (Royals), who date from 1650 and 1661 respectively. They ride ‘cavalry blacks’: beautiful Irish geldings. These horses are so engrained in cavalry life that even their hooves are stamped with a regimental number.

"They are men of extreme patience..."

The cavalry is unique in the British Army. Not only do they perform a ceremonial role in London, as our monarch’s bodyguards, but also operate a reconnaissance unit from their base in Windsor. But the ceremonial job is no picnic.

If our monarch is ever on the move in London – for the State Opening of Parliament or Trooping the Colour, the cavalry are there. If there’s a state visit, the cavalry are there, and they will have been up all night, for weeks on end, tirelessly rehearsing.

This side of the job might seem mystifying to the general public. Why, in 2017, does our monarch need a herd of mounted bodyguards? “It’s all about soft power,” says Lieutenant-Colonel James Gaselee LG, Commanding Officer at Hyde Park.

“We are one of those iconic bits of Britishness, providing reassurance to other countries of the continuity of Britain, and what we stand for.” Governments may come and go, but the cavalry will always be here. “Prince Albert designed our last uniform, and we’re still wearing it,” Colonel Gaselee smiles. “Our traditions can seem archaic, but they are an essential part of who we are.”

One of these is the cavalry’s daily job, the King’s Life Guard, for which 12 men and their horses move from barracks to Horse Guards Parade, via the Mall, to perform their protectorate role outside what was once the official entrance to Buckingham Palace.

Tourists gather around to watch the changing of the mounted guard, and the men, keeping a straight face, move on foot and horseback to a new position on guard every two hours.

Every afternoon is the 4 o’clock Parade, in which the duty officer from Hyde Park rides down the Mall, kitted out with his knee-length frock coat and sword to inspect the guards. This routine dates back to 1894, when Queen Victoria discovered her entire guard drinking and gambling on duty, afterwards ordering that an officer carries out an inspection every day at 4pm for the next 100 years, a tradition that King Charles III will continue.

For all the pomp and ceremony – of which there is a great deal: before lunch, Captain Albany Mulholland of the Life Guards remarks that he is already on his fourth uniform change of the day – it is worth remembering that these soldiers are real soldiers, who can, and do, drive tanks. “Everyone should see us as soldiers first,” Colonel Gaselee says. “There are people here with a huge number of campaign medals.”

Hyde Park is seen as the regiment’s tougher barracks. After passing through training, troopers – the cavalry’s name for what other regiments call privates – generally spend two years in London on ceremonial duty.

It’s the equine element that makes the mounted regiment such hard work, explains Corporal Major George Sampson, a four-time Afghanistan veteran, who joined the army in 1998. He may have spent most of his career at Windsor, leaving Hyde Park in 2002 and returning in 2015, but he grew up at Hyde Park.

“You’re made of steel, but this is the crucible in which that steel is forged,” he says. “This is where you learn to deal with anything. You cannot replicate it anywhere else.” ,

"The cavalry is unique in the British Army, but the job is no picnic...."

A typical day starts at 6am with the Watering Order, an hour-long exercise through the streets of London for horses and riders not on the King’s Life Guard that day. At 10am, after breakfast, those on the King’s Life Guard line up to be inspected, before moving off at precisely 10.28am to Horse Guards, passing under Wellington Arch en route, in full ceremonial kit.

There’s a lot of it: a tunic – navy for the Blues and Royals, and red for the Life Guards; a solid metal helmet, with a red plume for the Blues and Royals, and a white plume for the Life Guards; black jackboots dating from 1812; and a sword which clatters pleasingly when the horses trot.

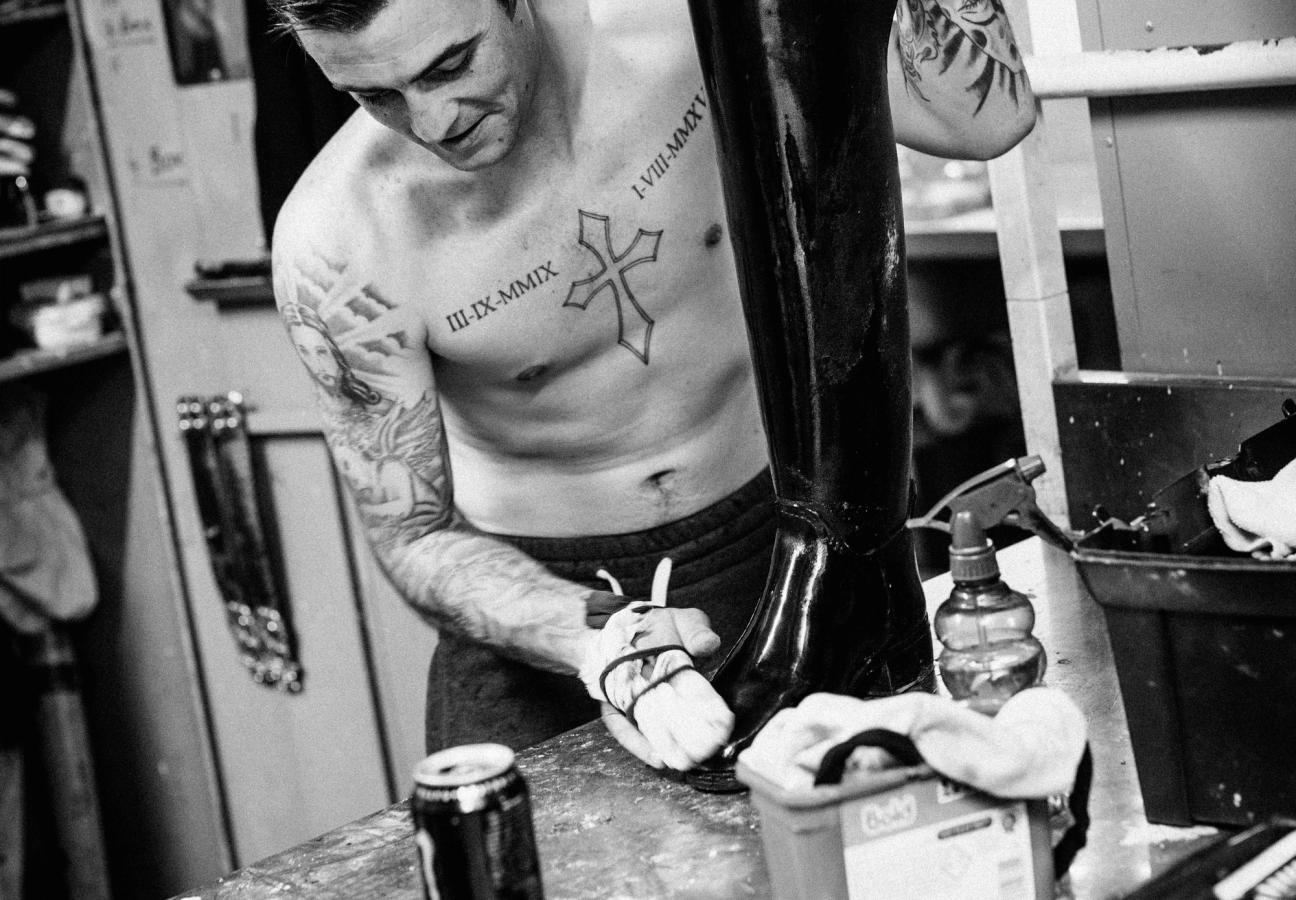

The majority of life at Hyde Park is spent cleaning – horses, stables, tack – or thinking about cleaning, for everything must look immaculate. There is even a competition for best turned-out trooper, the prestigious Richmond Cup, which, for the winner, is a serious achievement.

Time off from this, and all other work, is measured in hours, not days. Thirty-six hours a fortnight is pretty good going. “When I was trooping here, the record was six weeks without any time off,” Cpl Maj. Sampson says. But he wouldn’t change it for the world.

“The thought of doing anything other than this fills me with dread and terror.” Colonel Gaselee tries to put this hard work into perspective for his men. “I say to them, the Queen isn’t going to last forever. You will be on parade, and you will see her, and you may even talk to her, so you need to appreciate what’s been given to you.”

Like any army regiment, the men on site are split into officers and soldiers. As in the rest of the armed forces, officers are addressed as ‘sir’, and their boss is Colonel Gaselee. The son of a racehorse trainer, unlike most of his men he had prior riding experience.

This relates to one myth that the regiment would like to dispel – that they are, in fact, a gaggle of ‘Ruperts’, as one journalist put it, who could all play polo before they could walk. “Everyone has to prove that they can be an army officer before they come here,” Colonel Gaselee says. “But I suspect there was a time when it was more about who you knew.”

Admittedly, it does attract a certain type of officer: both Princes William and Harry served in the Blues and Royals. Exploring the kit stores, Lieutenant Piers Flay discovers a tunic that once belonged to W. Wales.

But most recently, the cavalry has been linked to the royal family for a very important reason. In July 2017, Major Nana Kofi Twumasi-Ankrah was named the Queen’s equerry. This is a seriously good advertisement for the regiment, Lt Flay grins. “And bloody well deserved.”

There is something extraordinarily intimate about Hyde Park, full of men with smart haircuts and shaven faces who, throughout the day, go from looking like stable hands to huntsmen to ceremonial soldiers. Colonel Gaselee describes his role as the “dream job”.

During the 4 o’clock inspection, as Lt Flay and I watch Captain Mulholland inspect the guards, we compare notes on who has the best job here. Me, for being lucky enough to hang out with them all day, or him, wearing his uniform. He reckons he’s got the better end of the stick. “I cannot tell you how much I love this job.”

But it is not the smell of horse manure that lures men to join up. “It’s that notion of adventure and a slightly higher purpose,” says 32-year-old Alex Owen, who retired this summer after 10 years in the army. “When you’re a child, you don’t play doctors and lawyers, you play soldiers, and that runs through most young men’s youth. The army was an itch I needed to scratch.”

Jim Eyre, who left the cavalry in 2015 after 25 years, having been Commanding Officer at Windsor, joined up inspired by the idea of “doing interesting things, travelling and working with great people”. Now commercial operations director at Harlequins Rugby Club in Twickenham, Eyre misses elements of service life – “the action and the camaraderie”.

Joining the Household Cavalry is more than just a job, or even a way of life. It’s becoming part of a giant family. Your choice of regiment, at selection, is “probably the single most defining decision of your life,” Owen says. “As a Household Cavalryman, the blood in my veins runs blue-red-blue, and it will until I die.”

Want more royal articles? Here’s how to brunch like a royal…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.