Members -- 10 days ago

Words: Harry Shukman

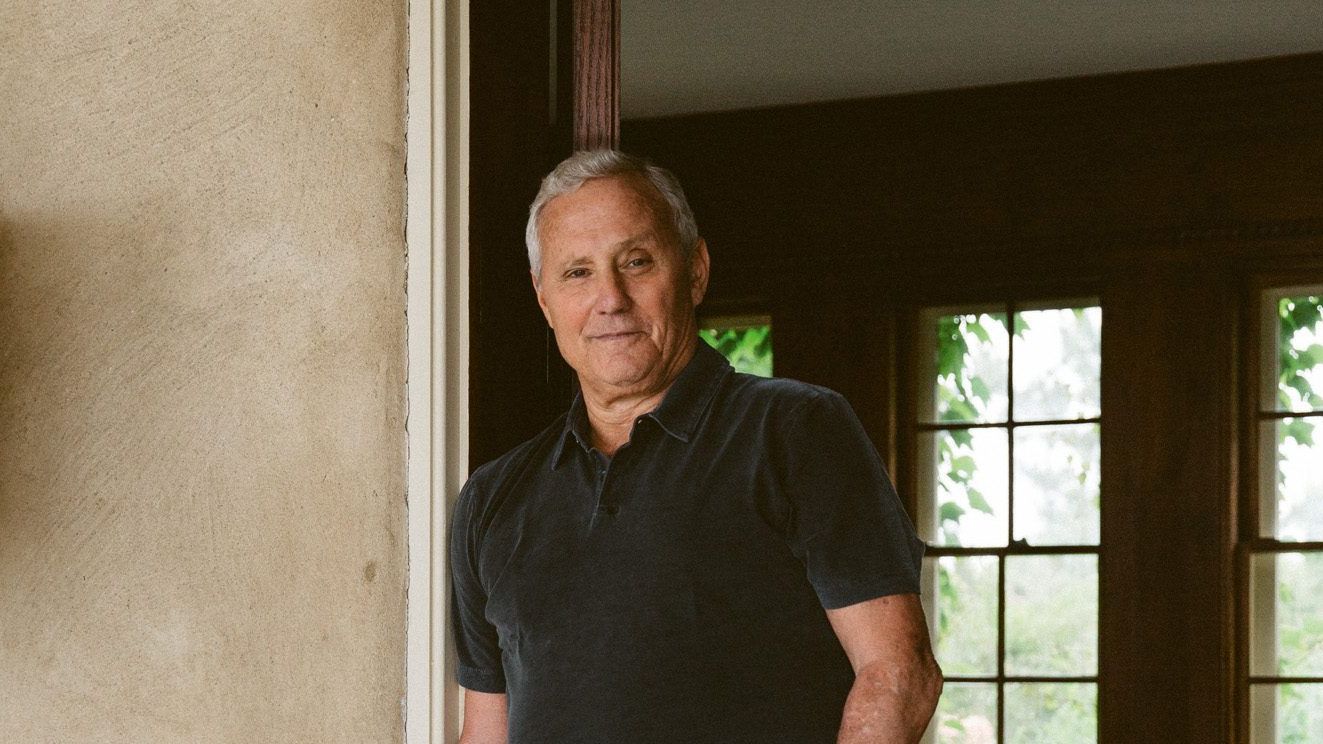

Photography: Fred Castleberry

Ian Schrager was the genius behind Studio 54 — the greatest nightclub ever to have lived or died. 42 years on from its peak, the PUBLIC hotelier and serial entrepreneur shows little sign of slowing down. At his beach house in the Hamptons, the King of Clubs talks to Harry Shukman about long nights, dark days and bright ideas.

To receive the latest in style, watches, cars and luxury news, plus receive great offers from the world’s greatest brands every Friday.