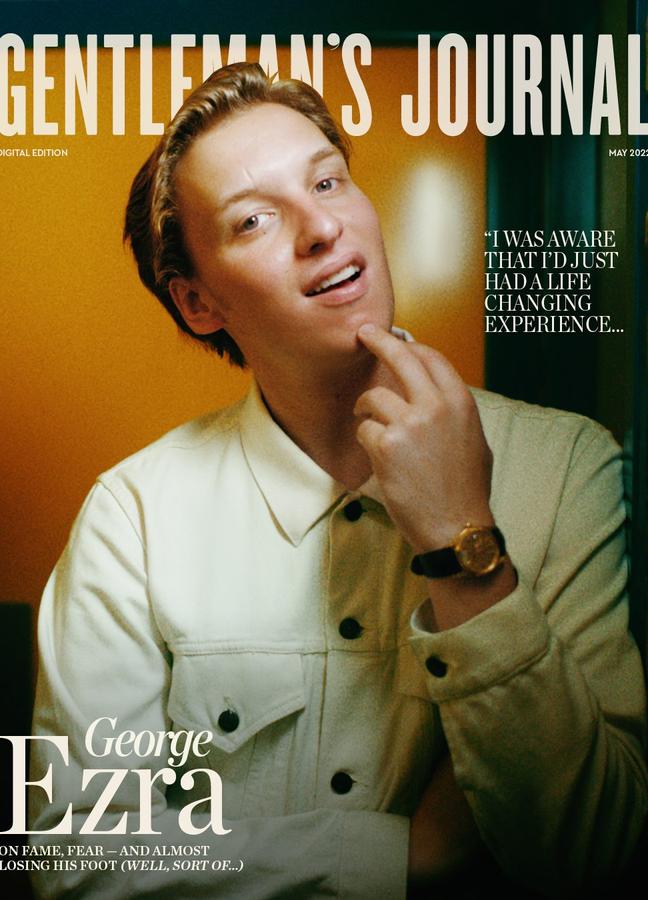

George Ezra on fame, fear — and almost losing his foot (well, sort of…)

His new album, the Gold Rush Kid, is his most personal yet. But can it replicate the life-changing, summer-soundtracking success of Shotgun et al?

I don’t know why, but I’ve been thinking about a line I once read on the back of a book. Stephen Fry, I believe it was, talking about the novels of P.G Wodehouse. “You don’t analyse such sunlit perfection,” he said: “you just bask in its warmth and splendor.” There’ll be no basking here, thanks Stephen — we’ve got an interview to write up. But the “sunlit perfection” I can get behind. George Ezra’s music is indistinguishable from the sunshine that so often accompanies it. It is warm and radiant and positive — all words that, as soon as you’ve written them down, make you realise how silly it is to try to sum it all up, like sitting in a glowing pub garden somewhere and saying “actually, sunshine’s pretty good, isn’t it?” to anyone that’ll listen. Just drink your continental lager and get on with it.

This isn’t entirely by accident, by the way — the whole summer thing. When George Ezra first heard the song ‘Shotgun’ played back to him in early 2018 — you know the one: “Homegrown alligator”; a bass line that appears to be wearing Persols — it made him “a bit nervous”, George says. “There was this excited energy around it,” he remembers, and he wanted to release it straight away. “And it was actually the head of the record label who said: ‘honestly, you need to hold off releasing that, because it’ll be much better when the sun’s out.’” George thought “that’s such rubbish.” But sure enough, the success of the single coincided with a mammoth British heatwave that summer, and it’s hard to know, at this point, which caused which. To me, the opening chords of that song bring down an involuntary cascade of balmy memories: a beach and a football somewhere; England vs Columbia, a penalty shootout; my four-year-old nephew howling along in the Zafira with little regard for lyrical accuracy or eardrums or hangovers. You will have your own associations, even if you don’t realise it now or aren’t paid by the word to think about it. But in 30 years’ time you’ll probably hear ‘Budapest’, say — George’s 2014 breakthrough — and get a glint of some dewy lawn in your early twenties, or a girlfriend’s perfume, or a barbecue not quite lighting in some shared back garden.

Much more interesting, though, is what these songs do to Ezra when he hears them now. “I love Shotgun,” he says. But the single is also wrapped up in several confusing, contradictory feelings. “I think it’s worth highlighting the fact that, on the last record in particular, I was extremely unhappy, actually. And I think it was self-inflicted.” Unhappy in what way?

“I felt very scared,” he says. “‘Shotgun’ is a song that did something that you can’t control. It got real mainstream commercial success, but there’s no real training for that. And this is why I say it’s self-inflicted. Because I was also a driven 24-year-old dude that was like, ‘yeah, let’s see how far we can push this,’” he says. “But then I think I got it into my head that it was going to change my life or change interactions.” George worried that he had to say yes to every opportunity, he explains; to chase every opening, and ride that bewildering train — even though he knew he would probably just be much happier at home, in Hertford, with his family and old friends, where he’d grown up, and where he still lives now. “But I just didn’t want to be that guy in the corner of a pub saying “I could have…’” he tells me. “Because I don’t know how interesting ‘I could have’ is…”

“So the unhappiness was that I just felt very stressed. And I think we rely on our twenties to try and figure out who we are in relation to the world around us. I was doing a very good job of convincing myself and then an audience that I kind of had an idea of who that was. And I didn’t,” he says. “But then, as these things go, the revelation isn’t actually that huge. You take one kind of side shuffle, and you go: ‘oh — you’re fine.”

George has a habit of addressing himself in the second person like this. I suspect he’s in constant conversation with himself in the way that we all are on some dim level — but in a way that must be turbocharged by the hydroponic light of fame; a steroid for maturity and introspection. He says that this new album, as it happens, sounds much more like him than the previous two. Not just lyrically or thematically — but vocally, too. When he first broke through, George’s voice preceded him. I don’t quite have the vocabulary here, but I’m told it’s a sort of bass-baritone, which feels about right: rich, round, mature. You want to spread it on toast. It first came about in George’s bedroom, he thinks — messing around, aping LeadBelly and Caleb Followill of Kings of Leon. But it seemed to fit. And it was a point of difference. “I’d moved to Bristol, and you couldn’t move for a kind of floppy-haired singer songwriter,” he says. “And I was aware of that. I was like, ‘oh, you’re one of these people’. And so, what can you do?” It is sometimes described as nostalgic; a voice from another time and place. Ezra’s new album is called the Gold Rush Kid, and it has nods to the wild frontier of the mid 19th Century. Does George ever feel as though he was born in the wrong era?

"It's worth highlighting the fact that I was extremely unhappy..."

“That’s the kind of thing that you’d say on a date to seem deeper than you are,” he laughs. “But do I? I don’t know. I find the modern world really fucking weird. I find it really, really odd…” he reaches for a specific example, but stops himself just short. “I just find social media really bizarre. I find that my relationship with it… I’m this adult that has to delete it from my phone. And what’s that? That’s something that’s more powerful than your will. And then I kind of pride myself on going through phases of turning my phone off at 9 PM. Dude — that’s not impressive…” he says. “But anytime I do it, I’m far more creative and engaged. I think more.”

There was plenty of time to think last summer, in fact, when George decided to go on a particularly long walk. “Yes. Me and two friends walked from Lands End to John O’Groats,” he says. “It was full on.” George brought the wrong kind of boots — leather, old school — because he liked the idea of passing them down to someone one day. He instantly regretted it. “Two weeks in, I had to go to hospital with a blister that was infected. They said it was showing signs of what would become sepsis — and there was this black medieval goo…” he says. (“We’re almost talking amputation,” I say. He laughs. “Sure. Let’s print the legend.”)

The trio walked for 95 days in the end, often up to 30 miles a day — camping for the majority of the time, pitching up in gardens and near-empty campsites, before drinking around the fire. (“And, honestly, we’d eat a family sized shepherd’s pie each…”) What did they talk about on the way? Were there some good conversational rabbit holes? “The best,” he says. “Like: If you had to put all of your chips on one conspiracy theory, which way are you going?” he laughs “And that could honestly last two days…” (George, if he had to, would put his money on something fishy going on with the pyramids, by the way.)

Were there more heartfelt, personal conversations, too? “Yeah, man, a lot,” he says. “I heard once that a lot of good chats happen between people — and blokes in particular — when driving, because you’re unable to make eye contact. And for the most part, we spent three months staring at the back of each other’s heels, marching along. And sometimes you’d almost catch yourself truly just thinking out loud — and it wasn’t even like you needed a response,” he says. “By the end, I was aware that I had experienced a life changing experience. And I think we’ve carried it with us. I certainly have.”

This leads us to George’s other lockdown project, a podcast he did with his best friend Oli called ‘Phone a Friend’. It was the two-blokes-in-a-car scenario, but in broadcast form — recording the pair’s candid conversations about exactly the sort of things best friends would talk about, but always underpinned by discussions of mental health. Even as I ask George about it, the phrases come out all wrong — “when we’re assessing the relationship around mental health…”, I start to say, like a bewildered government minister on a breakfast talk show. George, however, is much more natural at this stuff, and has become a genuine touch point for this confusing umbrella of topics — especially in lockdown, and especially for men. What’s that like? And what does he think of it all?

"It was showing signs of sepsis: there was this black medieval goo..."

“It’s unavoidable to acknowledge the fact that [talking about mental health] became, I think, somewhat in vogue,” he says. “There are, however, many ills and wrongs that don’t get spoken about. But something happened where collectively, we said: ‘this is something worth talking about and pursuing’. There was almost this mushroom cloud effect of people feeling empowered enough — liberated, inspired enough — to talk about these things somewhat publicly, to the point where I think we were desensitized to this thing,” he says. “The upshot of that, though, is that even the conversations I have with friends now — and separate to the fact that I’ve kind of actively pursued these conversations — are different to how they were before. And I don’t think there’s any bad that can come from that.”

I think about a moment on the title track of the new album, where George delivers a line — ostensibly from a doctor, but surely just from himself — that says: “You’re not alone, although you feel alone — you’re just like everyone, you’re holding on.” It is the essence of ‘Phone a Friend’ and so much else. But it’s slipped in via a bassline that’s utterly buoyant and beaming, like a dose of medicine in fresh lemonade. That song, by the way, is a natural successor to ‘Shotgun’, and forms the first half of the album, which bounces like a hot trampoline. This is the sunlit perfection. It is freshly cut grass. But then things take an elegant swing into more soulful, poignant territory, in a succession of songs filled with simple truths and self-reflection. They are often sadly sweet, and you want to cry during the final part of ‘I Went Hunting’ — more balmy lilting twilight, probably, than bright sunshine.

He is clearly in a different place than he was four years ago. “On the last record — with me finding that experience particularly difficult — that became the thing that kickstarted me having a lot of conversations with myself, with my family, with my friends, and sitting and thinking a lot,” he says, before speaking about the walk again. “We ended this journey, and it all felt very serendipitous. Getting to John O’Groats… somehow, it kind of felt like the right thing had happened. I don’t know.” he says. “But it definitely played a part in how I approached this record.” The previous two albums were characterised by jaunts abroad — diverting travel, hazy holidays; Australia, Budapest, Barcelona. It’s no mistake that this one feels much closer to home.

Earlier, when we were talking about social media, I told George that I had tried his trick the night before our conversation — turning my phone off at 9pm to sleep and think better (only to switch it back on a few minutes later, almost unthinking, before scrolling mindlessly into the small hours.) But it seemed like it was worth a try, at least. He laughs at that idea.“What would George do!” he says. But it’s really not such a silly mantra. George Ezra is very good at talking to himself. It is lovely, on this album and elsewhere, to be able to listen in.

To listen to The Gold Rush Kid, click here.

Read next: ‘At that moment, I set my younger self free’: All aboard the wild ride that is Francis Bourgeois