“I’ve been furious at all the people having fun, drinking in the streets. And I’ve been literally in the heart of it all, locked in a dungeon!” says Harry Hadden-Paton. It’s fair frustration. The actor is currently engrossed in a freshly launched West End run of My Fair Lady — the illustrious production’s first London showing in 21 years, and one in which Hadden-Paton plays the lead role, Henry Higgins, the phonetics professor whose role is underpinned by his flutter on a Cockney flower-seller.

We speak in the groggy hangover days that follow the Jubilee weekend, early in June, with the Downton Abbey star seemingly hoping for a little respite from work, aching to have had the chance to join the general-public’s four-day long, Lizzy-celebrating bender.

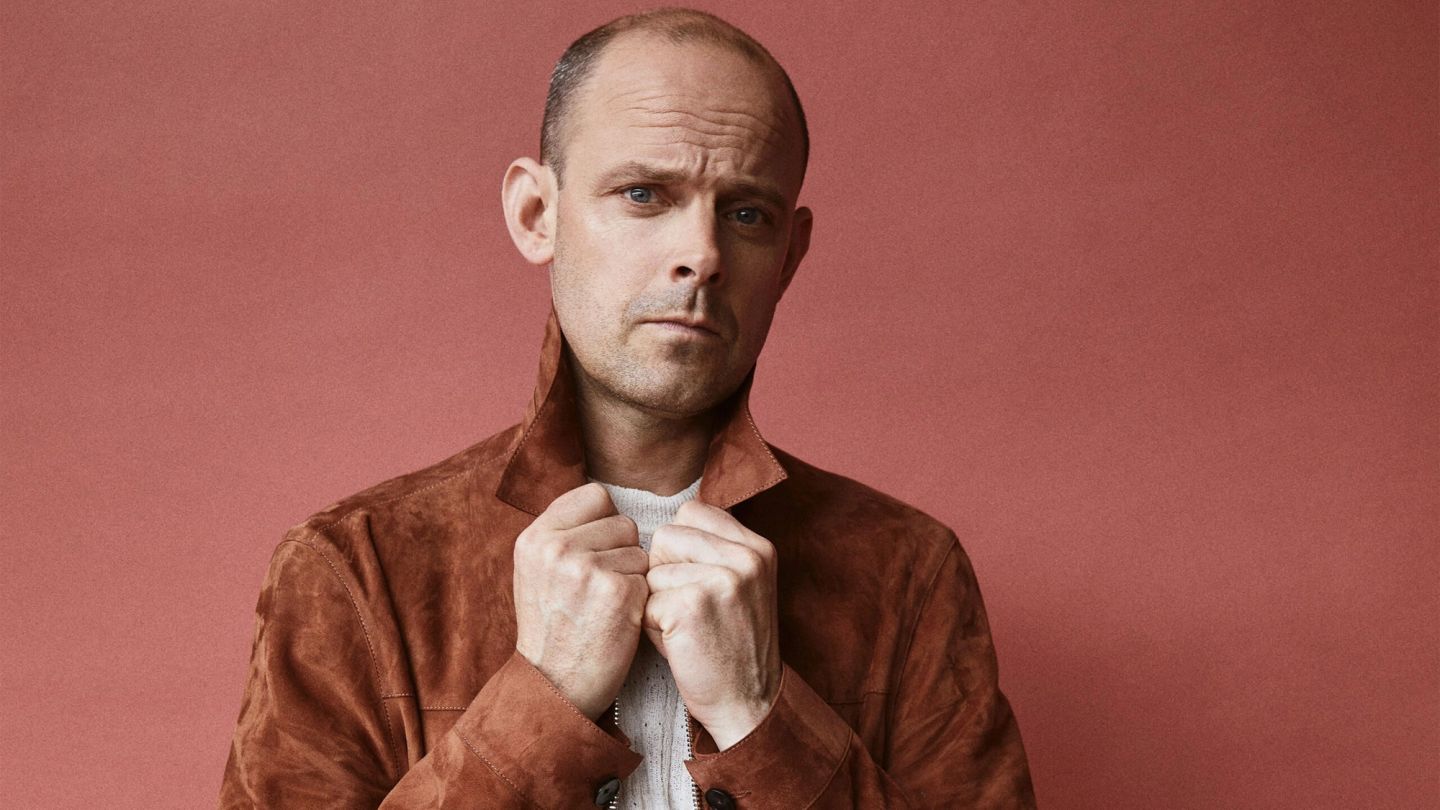

Jacket, Giorgio Armani; Polo shirt, BOSS.

There’s a slight touch of irony to this, it seems, given that some of the most famed roles undertaken by Hadden-Paton, 41, are deeply interwoven into various regal narratives. There was Bertie Pelham, the 7th Marquess of Hexham who was responsible for giving the perpetually down-of-luck Lady Edith her joyous ending in the television series Downton Abbey, a global juggernaut that beamed Hadden-Paton’s star stateside; Martin Charteris, the amiable private secretary to Claire Foy’s Princess Elizabeth in The Crown; and King George VI in The King’s Speech, the Chicago Shakespeare Theater’s production of the Oscar-winning film about the young head of state fighting to control an incapacitating stutter.

It is a low-hanging fruit to typecast Hadden-Paton as a period-drama specialist, all buttons firmly done up, every shirt starched – the type of characters that “come in and cry for a little bit,” he said, in 2018 – but he is, with no doubt, an actor with broad range, having also brought his own takes to the live stage, with characters such as Aldous Huxley, the Brave New World writer who, in the fictional Broadway musical Flying Over Sunset, explores the deepest parts of himself when dropping LSD with Clare Booth Luce and Cary Grant; and more recently as My Fair Lady’s bullying Higgins, which shows at the London Coliseum until the end of August.

Below, we go Zoom to Zoom with Hadden-Paton to talk about accuracy when portraying historical characters, why he craves a villainous role in the future, Rubik’s cubes in lockdown, quarantining in the south of France while making his most recent film, Downton Abbey: A New Era, and what comes next…

Jacket, jumper and trousers, Mr. Porter; Trainers, John Lobb.

GJ: You’ve played the King of England, Bertie Pelham, Henry Higgins and Aldous Huxley, to name a few characters. But what is it about playing such a wide range of roles that appeals to you? Is it, I assume, a holistic thing?

HH-P: Yeah, and it’s also what I happen to be good at – I have a facility with language and the text, which is maybe denser than contemporary text, and I really enjoy the puzzle of unlocking it and making it feel fresh and spontaneous. I also get a lot from doing things that are period – the costumes and all that adds so much. Everyone was so restrained in waistcoats, that it kind of adds to the barriers, the things you aren’t allowed to say, the things you’re fighting against to get your feelings and thoughts across. Having said that, I’m looking forward to diversifying a bit as well [laughs].

When you say you want to diversify, what would appeal to you?

Anything – I haven’t worked with different accents for ages. I can heighten my own accent or lower it. But I definitely want to be working more in America – we had a ball out there. And I want to crack open that nut and see what’s going on over there. But it’s equally really fun to be back in England.

Is there any type of role, or specific role, that you’re keen to play, whether in America or the UK?

I’m quite up for villains at the moment – monsters, essentially. I’m not going to be jumping into anything after this [My Fair Lady], I’m going to take a moment. But I want to really get under the skin of someone different, which I guess is always the case, but I want to push myself – I’ve been doing this job for a while. And the greatest challenge at the moment is just the physical, doing it over and over again and keeping it fresh every night.

You’ve once said there’s a sort responsibility to getting historical characters right, for both their memory and for the audiences’ expectations. So, are you of the opinion that accuracy and authenticity are non-negotiable when portraying non-fictional roles?

No, not at all. I guess it depends who it is. You don’t have to necessarily like [your character], but you have to empathise with them, you have to know what’s driving them and understand that. It’s useful for the audience, so they can hook in and know who you are, but then, of course, you tend to be dealing with dialogue that wasn’t their dialogue. I played Bertie [George VI’s family nickname] in The King’s Speech, in America, recently. And then some of it was his speeches, verbatim – the play ends with him reading the speech that I think is at the end of the movie. And so you can break down, frame by frame, what he did, there is footage of him doing that speech.

But it loses some spontaneity, you’re also onstage anyway, you’re reacting to what’s in the room with the audience. And every night, something’s going to tickle them in a different way, and it’s my job – and this is why I love theatre – to manipulate them and play off their energy and work out how it needs to be different tonight to how it needed to be different last night. If they’re listening particularly well, I can heighten the tension in the room. If someone’s coughing, they’re clearly distracted, so I need to crack on until we get to the next bit.

So I think audiences come to something like that with the expectation [of accuracy], and you don’t want to disappoint them by just not doing that – you tend to not want to disappoint them anyway [laughs]. You want to give them an element of that, but you also want to make it fresh and relevant for today. That’s the point of doing revivals, and why I love doing this show – My Fair Lady hasn’t been done for twenty years, and look how much has changed since then.

Suit, Richard James; T-shirt, Peregrine.

How do you feel about embodying a flawed character such as Henry Higgins, especially given today’s climate? Is it kind of daunting but enjoyable to update that?

It’s a bit sadomasochistic, isn’t it? What I love about this is that it is a play. I never intended to get into musicals, but it is a play with songs. And what George Bernard Shaw [the playwright whose Pygmalion was the basis for My Fair Lady] created was a character who… there’s enough there that I completely believe him and his humanity. I was obviously worried about it. He is a flawed man – yet I have to empathise with him, and that’s tricky at times.

I guess, he’s a genius – he’s one of these sort of archetypal Sherlock or Doctor Who characters that if they were around today, they might find themselves on the spectrum somewhere. And so I’ve really kind of leant into that. And so it’s actually a lot of his cruelty comes from a kind of innocence and a misreading of social cues and a misunderstanding of how to communicate better. So it is a three-hour struggle of a man trying to communicate. Now I’m talking about it, it’s a bit like the stuttering [from The King’s Speech].

As soon as you become kind of louche and at ease with the insults, then it doesn’t work nowadays, it has to be something that he’s struggling to get right. She’s got the battle [Eliza Doolittle, the Cockney flower girl who receives elocution lessons from Higgins, and who is subject to much of his misogyny], she’s got the journey of trying to better her place. I could talk about it for hours, but the whole play is about people trying to change, but ultimately not being able to change at all, and not needing to change. It’s not the accent and the bearing that turned Eliza Doolittle into a princess – it’s the fire that’s inside her that we see right at the beginning.

With it being the first major West End revival of the show in two decades, is the task charged with a sense of occasion? Or is it daunting or exciting? Both? Or have you not really given it any sort of thought?

It is really exciting. I was excited at doing it on Broadway [in 2018], because it felt like an occasion. But coming back and doing it in a theatre that’s 100 metres from where it’s set… I go and have my sandwich next to the columns of where the first scene takes place. And having this debate about language and class, and in this occasion, race, play out in London, where these conversations are happening and more on the nose than they were in America… You know, there’s a lot of the language, a lot of the texts, that went over their heads, a lot of references.

Jacket and trousers, BOSS; Jumper, Begg & Co; Boots, Harry’s of London.

So it feels right being done here?

It does feel right, yeah. And we’re really lucky to have an excellent cast doing it. It feels alive, and doing it in the Coliseum feels like an event. It is beautiful. Just coming here and doing it on this stage, in this sort of splendour, is very special. It’s value for money is what I would say, because, as far as I know, it’s about the biggest orchestra that’s done a musical in London. We’ve got 170 orchestra players revolving because of Covid. And there are 30-something in there every night. It’s extraordinary. And you don’t get that every day. It is a real event.

You briefly touched on it before, with the American audience and some texts that went over their head – when the play was shown in New York, did you find there was a noticeable, or even subtle, difference between British and American audiences and fans?

There is a bit, then there’s bound to be [in relation to] what sort of cultural references they pick up on at that particular moment in time. The standing ovation is just slightly… I was really excited. I remember the first preview, when they’re all on their feet, I was in tears going, “Oh my god, we’re a hit!” And then everyone said, “No, they just do that.” [Laughs].

So it was with trepidation that I came back here. But I’m relieved that we’re getting them every night here as well. Maybe people have just caught on to the American way. But I hope not – it’s nice to feel like we’ve earned it. After three hours, you do feel like you’ve earned a little pat on the back.

Jacket, BOSS; Jumper, Begg & Co.

Briefly, just going into the latest Downton film; can you tell me a bit about that period when you were all in your bubble, filming in the south of France?

It was an extraordinary privilege. Firstly that we knew it was coming, so there was a light at the end of the tunnel of all those months of making sourdough and planting vegetables and learning the Rubik’s Cube. I ticked all them off. But having that at the end of the tunnel was amazing. And jumping into a show where we all know each other and love each other and know how it works was amazing.

They obviously – with Covid – took it so seriously. And we were testing every day, and when we went to the south of France, we had to quarantine for a week before we could start filming because then we were working with a French crew. I mean, you can fill in the blanks of what quarantine in a hotel in the south of France was like, but it was fine… my wife was furious because I was FaceTiming from the pool!

On that note, I was told that you have a few projects in the pipeline, with your wife, that you can briefly mention, but probably not get into too much detail about. Would you be able to share anything at all?

You don’t want anyone to nick your ideas, but we’ve been busy writing and developing things all through lockdown, to keep the brain going. But also, we both feel like it’s time to tell stories ourselves.

Were these planned pre-lockdown? Or did they just happen?

Well I’ve always done it a bit. I’ve got a few screenplays up my sleeve that I’ve done over the years, and I’ve collaborated with other people. And it turns out, we work quite well together, which is nice. In-between raising three kids, we managed to find time to spitball, and so we’ve got a few things we’re working on that actually cover quite a wide range of subjects and media. So I’m going to really pin down what they are, because it’ll all be about timing and what’s most relevant at the right moment.

Suit, Giorgio Armani; Jumper, Mr. Porter; Loafers, John Lobb.

So there are no set dates?

Not yet. Once we get some things tightened, it’ll be going out to people that we want to be in it. And when you get names involved, then you can start the funding. But it’s fun to use other parts of your brains.

This was done throughout the whole two years of the pandemic, I assume?

We were in New York for quite a lot of lockdown because I was doing another show over there, and they didn’t know how long Broadway was going to be shut down for. So we waited for a week. And then they said, “Well, let’s wait another couple of weeks… and then wait, maybe a month.” And then four months later, we were still in the eye of the storm, which was pretty scary, really. And then we came back and made our base in the country, in Dorset, which we love. I mean, it’s heaven.

* This interview has been lightly edited for clarification. My Fair Lady runs at the London Coliseum until 27 August.

Want more great British actors? Read our latest cover interview with Tom Hiddleston…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.