The life and legacy of Gianni Agnelli, 22 years after his death

The talismanic head of Fiat, Ferrari, Juventus FC — and a dynastic clan often labelled ‘the Kennedys of Italy’ — remains more beguiling than ever…

- Words: Joseph Bullmore

It usually starts with the watch. Which is a bit like saying: “for Jesus, it begins with the sandals” — a little reductive, perhaps sacrilegious, wilfully ignoring the halo or the thorns. But Gianni Agnelli’s watch — or, more correctly, how he wore the watch — has long been the lure that pulls us into the myth. It’s the sparkling, pretty fishing fly, bobbing gently on the surface of some calm Lombardy lake, which immediately drags you down into a whirling vortex of Italian sports cars, slicked-back silver hair, mid-century boardrooms and exquisite manners.

An alligator-strapped, pale-faced day watch, fastened sturdily to the outside of a powder-blue French cuff. You see what you want in it. A tycoon too busy even to lift his sleeve to check the time. A careful flourish of Italian sprezzatura. An innovation, an inside joke. Graydon Carter, the former Vanity Fair editor who made a documentary for HBO titled simply Agnelli, says the whole thing was purely practical: “He was one of the first people to wear these gigantic steel watches, and it was simply too large to fit under the cuff — it wasn’t a style thing.”

Another rumour maintains that Agnelli disliked the harsh feel of cold metal on his skin. Jean Pigozzi, tech investor and the world’s best-connected man, claims that it was just an old Piedmontese custom — a way to ensure you didn’t wear down your shirt cuff with your watch face; an act not of showiness but of preservation.

In reality, it was probably a bit of both. For Gianni Agnelli, style and pragmatism seem to have been one and the same. A Ferrari is not beautiful because of its flowing lines — it’s beautiful because it goes faster because of its flowing lines. The form is more lovely because of the function, and the function is finer because of the lovely form.

Once you work that out, you start to see the enduring appeal of Gianni Agnelli — L’Avvocato, the ‘Henry Ford of Europe,’ the the man who would be king. Agnelli would almost certainly have scoffed at a too-modern word like “lifestyle.” But in essence he invented the concept. Life and style — like work and play, joy and danger — not separate and distant, but pressed cosily, naturally together. So everyone copied the watch trick — “absolutely everyone”, says Pigozzi — not because they wanted to wear their watch like Agnelli, but because they wanted to live their life like him.

Gianni Agnelli was born in Villar Perosa, a small commune southwest of Turin, in 1921. His grandfather, after whom he was named, had set up the Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino (FIAT) in 1899, and brought mass-produced cars to continental Europe. The family was rich, powerful, worldly, connected. Agnelli’s mother, Donna Virgine Bourbon del Monte, was eccentric and bohemian, and kept a pet leopard on a chain. His father, Edoardo, was an aesthete and art-lover, who died, when Agnelli was fourteen, in a seaplane accident — decapitated by a propeller after the craft capsized.

In the wake of the tragedy, Agnelli, the eldest son, tempered his mischievous constitution with a new-found maturity. “The person he admired the most — the person he feared the most — was his grandfather,” says Alain Elkann, Agnelli’s son-in-law. “And when his father died, he had to convince his grandfather, who was very much his tutor, to let him go to war.”

In 1943, bound by a sense of duty — and a feeling that “an Agnelli must be brave even in a war” — Gianni joined a cavalry unit that fought in North Africa and Russia, and was wounded twice on the Eastern front. (A third injury, possibly based more in legend than in fact, occurred not on the battlefield – but in a bar, over a girl, when a German officer is said to have shot an over-amorous Agnelli in the arm.) When Italy changed its allegiance away from the Axis powers later that year, he fought gallantly with the resistance, while his fluent English made him a useful liaison for the incoming American troops.

“He distinguished himself in the war,” says Alain Elkann. “And he gave a lot of importance to the experience. He had been a soldier and then an officer, and this gave him a lifelong discipline.”

When the war ended, Agnelli’s grandfather — who had manufactured vehicles for the Italian Axis armies — was forced to retire. Gianni Snr named longtime associate Vittorio Valletta as his successor, while the young Gianni was left as the de facto head of the family. Though seen as the natural heir to his grandfather’s empire, the sense was that Agnelli would need time to grow — and blow off some steam, perhaps — before slipping into the hot seat.

“He had a certain group of friends that fought in the war that felt despair”, one of his old pals explains in the HBO documentary. “They felt the only thing left for them in life was to amuse themselves — to go with women, to drink, have cars, all of that.” Before the war, Agnelli had completed a law degree at the University of Turin, earning himself the lifelong nickname ‘l’Avvocato’ or ‘The Lawyer’. It was an epithet that, from the off, seemed more ambassadorial than litigious; an advocate, a campaigner, and a promoter rather than a humdrum solicitor. This, to many, was the role Agnelli played most significantly for the rest of his life: a diplomat of Italian hard and soft power; a Prince-at-Large for his country and its people; and a protector, most of all, of that most serious of institutions: fun.

“He distinguished himself in the war...”

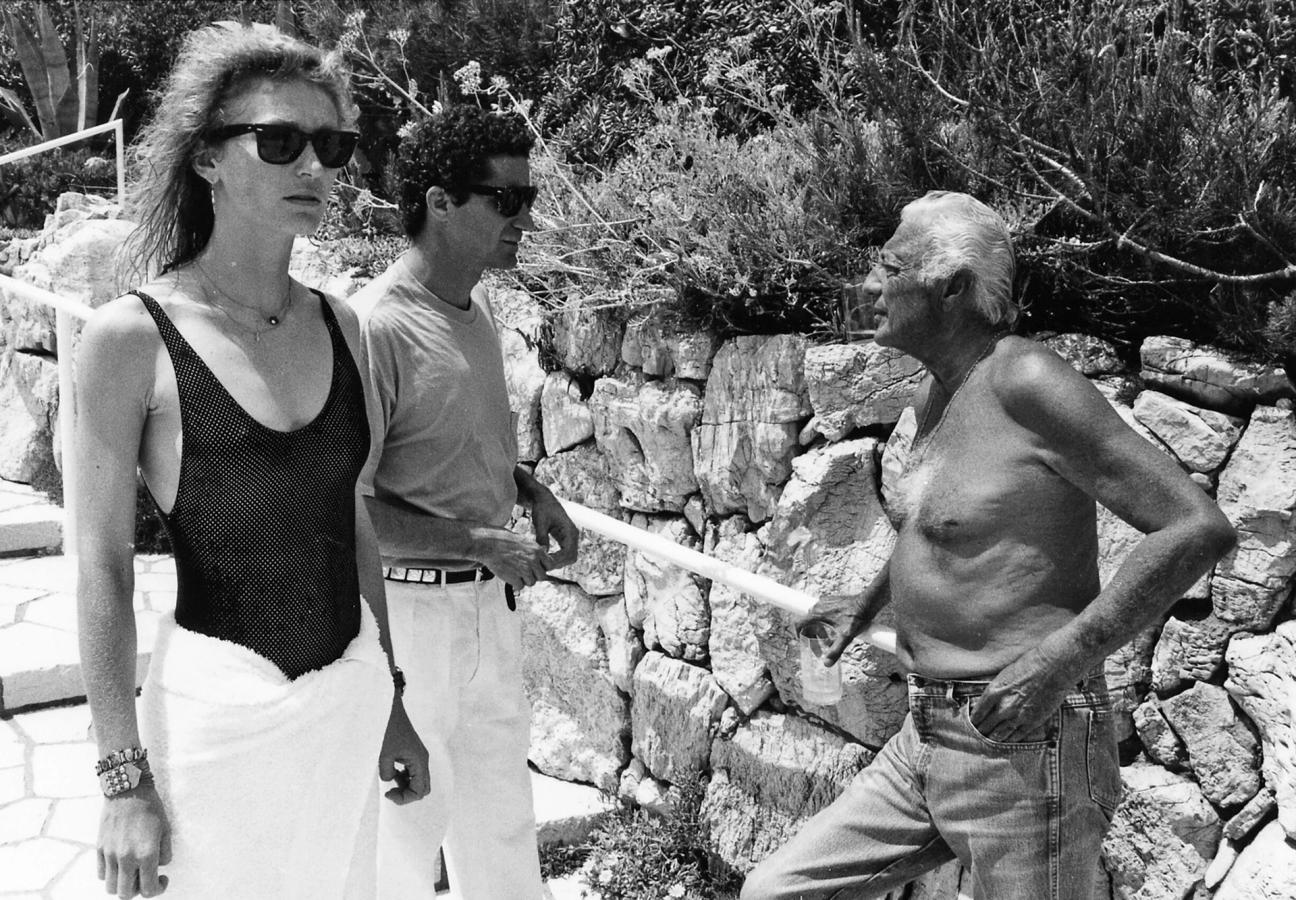

“All the stories are true,” begins Jean Pigozzi. And there are plenty of stories. The naked swandives from helicopters into the Adriatic. The drag races through the streets of Paris or Milan. The rolling, carnival house party of the 1950s French Riviera. “He was not shy.” The Agnelli lifestyle was not at all characterised by the dolce far niente, that sleepy Italian art of doing precisely as little as possible.

The man did it all, living life as if dancing in double time to those sashaying around him — a proto-playboy, and by far the jettiest of the newly-formed Jet Set. Lunch in Milan, dinner in Paris, dessert in Monaco — and a bed just about anywhere he liked. In and around Agnelli’s marriage to the formidable Marella Caracciolo dei Principi di Castagneto — an elegant, lithe aristocrat, and the most swan-like of Truman Capote’s famed society Swans — the Fiat heir entertained affairs with Anita Ekberg, Rita Hayworth and, if the rumours are to be believed, one Jacqueline Kennedy. (“You fall in love at the age of twenty,” he once said. “After that, only waitresses fall in love.”) A dalliance with Pamela Churchill Harriman — recently divorced from Randolph Churchill, Sir Winston’s son — brought Agnelli closer to London high society, but caused him trouble as soon as it ended.

“One summer, I was in Rome with Gianni,” says Taki Theodoracopoulos, the society writer and almost certainly the last of the true playboys. “And suddenly this man attacked him. Gianni just brushed him off. The guy was drunk — and I realised it was Randolph Churchill, screaming: ‘you ruined my wife, and now you’re trying to ruin my son!’” Taki says. “All Gianni had done was given a little boat to young Winston Churchill. It was a tiny boat that you could take to the sea and drive, but it was for a 12 year old. Not such a big deal.

“But he was very brave physically. Not a tough guy — didn’t know how to fight. But very brave,” Taki says.

“He was very seductive, mainly because he was so much fun and so good looking,” explains Pigozzi. Diane Von Furstenberg once described him as “irresistible,” adding: “it was not possible not to be seduced by him.” In 1962, Jackie Kennedy took her children, Caroline and John-John, to the Amalfi Coast, where they met and spent time with Agnelli and his coterie. John F Kennedy, then the Leader of the Free World, became so wary of l’Avocatto’s charms that he sent an immortal telegram to his wife. “More Caroline; less Gianni.” Was Jackie seduced? “With those meteors crossing the sky,” says Carter, “it strikes me that it was only a matter of time before they passed very close to one another…”

Naturally, the king needed a court, and Agnelli soon attracted a particularly colourful set. Jean Pigozzi was taken under l’Avocatto’s wing as a young man in the 1960s. “And I was very impressed by him. Immensely charming, fun, with nice boats and helicopters and planes: all the toys you could dream about.” Taki met him at 19. “He befriended me when I first arrived on the Riviera playing tennis. And it just simplified my life completely,” he says. “It was a very tight, closed society. But he took me around that first year, and I met everyone. Suddenly I was welcome everywhere.”

Agnelli was a friend and spirit guide to the likes of Porfirio Rubirosa, Aly Kahn and Gunter Sachs, leading by example in the playboy art. “You picked up a lot from him,” says Taki. “There’s the old thing that you can tell a man by his boat and by his woman, which was very, very good advice.”

Pigozzi remembers his manners, most of all. “The one thing you learned from him was to be nice to everybody. From the fishmonger to the president of a car company to a big politician to a pretty girl — he spoke to absolutely everybody in the same, very pleasant tone.” Taki remembers his “impeccable, old-fashioned manners”, and how “everyone around him started to speak the way he did, to dress the way he did” — an imitation that was not always taken as flattery.

“There was this one rich guy who always copied him, and would go into the same tailors and ask them what Mr Agnelli had just ordered,” remembers Pigozzi. “They’d say: he ordered two blue suits, a grey suit, and a striped suit. And every time he and Agnelli saw each other, the guy would say: ‘it’s strange, you have the same suit as me — I don’t know why!’

“So one day, Gianni went in and ordered a horrible pink suit. Really horrible. Then three months later in the summer he saw the same guy with the same horrible pink suit. Gianni said: ha! I’ve got you now!”

“He had a sense of humour,” Pigozzi continues. “He was not a pompous bore. You wanted to be with him because he always had such a good time. He would move, move, move, the helicopter, the sailing boat — dropping into a gallery, spending three minutes in a museum, on, on, on; faster, faster — never staying put for five hours in the same place.”

The cars helped. Agnelli drove like a getaway driver on a freshly slicked Autobahn. “Of the many ways to die, I don’t think an accident is the worst,” he once said in an interview. “There are infinite duller and more unpleasant ways…” Red lights? Speed limits? One-way streets? Forget about it! You half expected to see Agnelli crash through a stack of watermelons in his Ferrari 365 Berlinetta, or narrowly dodge two workmen with a plate glass window.

“He drove like a maniac,” says Taki. “But he was a very good driver. We once had dinner with Nikki Lauda. Gianni was late, and I asked Nikki how good he thought Gianni was as a driver. He said: ‘he’s nothing like me, but he’s very, very good for an amateur.’” When the police would catch Agnelli speeding — in Milan or Manhattan or Mayfair — they would pull him over, but only to catch a glimpse inside his one-of-a-kind sports cars, resplendent in bespoke leatherwork and hand-turned woods. L’Avocatto seemed utterly immune from mortal concerns or pedestrian fears (a symptom, perhaps, of the bravery and boldness he had shown at war.) Until, suddenly, sprawled out beneath a heap of twisted metal and a cloud of hissing smoke on a road above Monte Carlo, he wasn’t.

Fleeing from a lover’s tiff — and having engaged in what Taki calls “les grands nuits blanches” in reference to his penchant for cocaine — Agnelli drove his Ferrari into the back of a meat truck at 125 miles an hour on the winding Corniche. He broke his leg in seven places, and skied with a metal brace for the rest of his life. No-one ever heard him complain about the pain, but the jolt of the crash — the signal from on high to slow down — seems to have stuck with him. Either way, far away from the froth and fun of the Riviera, Italy was slowly descending into a chaos that would prove a much graver threat than any playboy collision.

They called it the Days of Lead: heavy, dull and grey, riddled with bullets. By the mid-1970s, spurred on by economic downturn and constant political turmoil, a communist paramilitary organisation known as the Red Brigades had begun picking off dozens of high-profile businessmen and politicians — often in grisly, broad-daylight executions designed to send fear through the ruling classes. Aldo Moro, the prime minister, was kidnapped and murdered after 55 days in captivivty. (Shot ten times, his body was left, covered in a blanket, in the back of a Renault 4 on a backstreet in Rome.)

"He drove like a maniac, but he was a very good driver..."

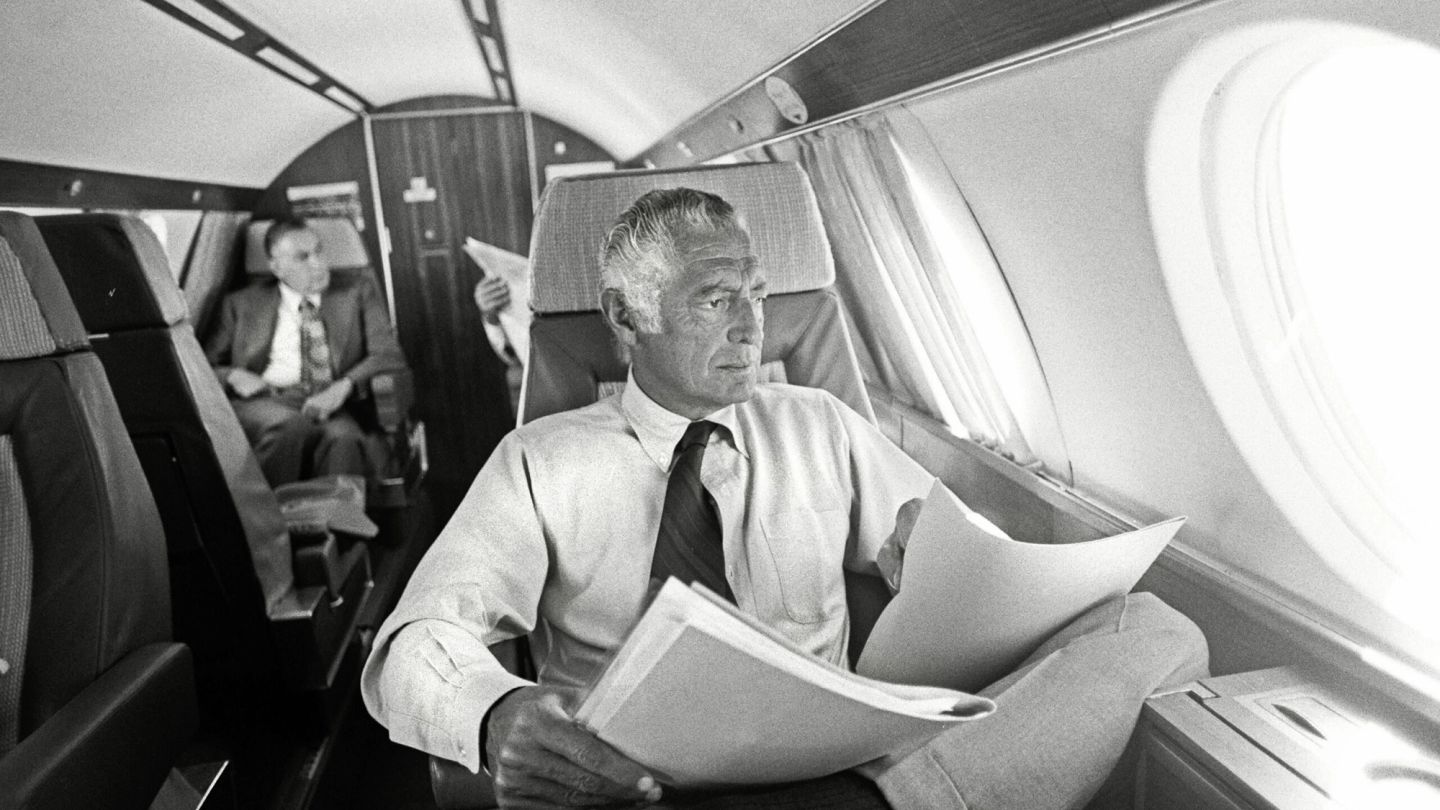

Agnelli, who had ascended to the Fiat chairman role in 1966 and had a celebrity sheen like few others, may as well have had a target painted on the back of his Caraceni suits. The chairman could easily have ruled from afar, secure in any one of his houses and offices from Paris to New York. But the people of Turin viewed him as something of a Prince-General to the city, that ancient military fort town — and Agnelli was determined to stay on the front line with them.

Every day, without fail, l’Avocatto would drive his own car (a mid-range Fiat, modified with a powerful Ferrari engine) from his home to the vast Fiat offices — a flag-bearer of immense calm and confidence for a fractious, cowed nation.

“He had an attachment to Italy, and a notion of service,” explains Alain Elkann — and an aura of permanence, perhaps. (The old story goes that Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev once took him aside, during a meeting of Italian cabinet ministers, and said: “I want to talk to you because you will always be in power. That lot will never do more than just come and go.”) Nick Hooker, director of the documentary about his life, says simply that “he thought that a day when someone tries to assassinate you and fails is a more interesting day than when they don’t.”

“Yes — he drove in every day, very fast around Turin,” remembers Taki. Back in London, and writing for the Daily Express, the society columnist invented a rumour that lingers to this day, but which was originally designed simply to protect his great mentor from the Red Brigades. “I made up that he had a pill in his mouth, and all he had to do was bite down hard enough and he would be dead,” says Taki. “My thinking was that he couldn’t be caught if people thought that — because why catch a dead man? Gianni didn’t mind. Marella was furious.”

The myth, like all great myths, has a ring of truth about it even when — or perhaps especially because — it sounds patently, screamingly fictitious. If anyone would rocket around their city in a secretly modified family saloon, bating terrorists with a cyanide capsule clasped under his molars — wouldn’t it be Gianni Agnelli?

The turmoil continued — strikes, protests, bankruptcies and murders — with increasing scrutiny and pressure placed on Agnelli, the ultimate captain of industry. In October, 1980, a trade union action blockaded the Fiat factories, stopping workers from entering. Frustrated, they decided to walk en masse to the Turin offices — numbering a momentous 40,000 — and soon broke the picket lines to re-enter their workplace. Agnelli knew then that the storm had been quelled — and many saw him as the calm, formidable hand on the tiller that guided the city through its most turbulent period.

Throughout it all, Agnelli never lost sight of the good life. Not much point staying alive if you can’t live, after all. One of his greatest indulgences, right up until his final days, was gossip. Who was where, who said what, who danced with whom — who’s in, who’s out; who’s been caught, who got away with it. “He loved gossip, and would call me up early in the morning and say ‘what’s new, what’s new!’” remembers Pigozzi. “And if you had no good gossip he would hang up on you. He had no patience — you better have some good stories to tell him that morning…”

Taki recalls how “you’d answer and he would say immediately: “dimmi tutto — tell me everything.” And you had to tell him something interesting. I started making stuff up…” Agnelli woke early — around 5.30 am — and the calls would start at once: to Lee Radziwill, to the Duke of Beaufort, to Henry Kissinger, to Jean Pigozzi; “to that ghastly Jacob Rothschild, and to David Somerset, and to me”, remembers Taki. “In all my houses, I now have a button that says ‘Do Not Disturb’ on every phone,” says Jean Pigozzi. “That’s because of him, because he used to wake me up very early.”

This love of gossip, worthy of a Milanese parrucchiera, stemmed, ultimately, from one of Agnelli’s most marked traits: his omnivorous curiosity. “He was very interested in the things he was interested in,” says Alain Elkann. “And he had a great eye. He was as interested in an impressionist painting or in a football player as in an automobile engineer or a foreign policy.”

Pigozzi remembers how “he would go to the Ferrari factory, and they’d show him all the new models. And he’d say: I want to speak to the guy who does the mufflers. And he’d meet this old guy, and they’d spend hours working on the sound of the new Ferrari muffler. He was interested in amazing details like that. I don’t think the president of Ford would have been spending time on those details.” For Agnelli, it seems, knowledge and understanding were simply the first half of good taste. The second part, however, was something impossible to learn or study — personality, individuality; sprezzatura or je ne sais quoi, perhaps. Taste, in the language of the modern titan, was his superpower.

“Yes — he had unbelievable taste,” says Pigozzi. “Really. How he dressed, how he looked and the boats he had.” Taki recalls how “he was simply the best-dressed man. He used to take his time. Caraceni [the great Milanese tailor] came to him. And his great fear was not to appear stylistically perfect. I don’t just mean sartorially — but everything. The remarks had to be good. What you read had to be good. I would say his weakness was that everything had to be perfect…”

Perfect, yes — “but not conventional,” says Pigozzi. “Always slightly weird and amusing.” Aside from the watch trick, Agnelli was known for other quirks. The wide blade of his tie was always shorter, much shorter, than the tail — like a startled schoolboy. He wore heavy hiking boots with his beautifully tailored suits (a nod, perhaps, to the hills of Piedmont and to his military service.) And he always unfastened the collar buttons on his Oxford-style shirts, so that their points might be free to gallivant on their own.

“He had very elegant double-breasted suits, but if he had a sweater underneath he would put his tie on top of the sweater, which was kind of weird,” says Pigozzi. “And that’s really something I learned from him. The nouveau riche, and all young successful Silicon Valley people who make a lot of money — they either build a house that looks like Versailles, or they build a house that looks like an English country home, or they stay at the Four Seasons at Hawaii and pay $6,000 a night in the presidential suite, and think that’s a good thing. But Gianni was completely different. He had his own style.”

This, perhaps, is why Agnelli seems to glow so brightly now, like a green light at the end of some distant dock, even 20 years after his death. The last two decades have not always been good to the good life. Paparazzi killed discretion and Twitter, now X, killed manners. Emails killed normal business hours. Algorithms outsourced personal style, warped taste, muffled individuality. And rich people nowadays are almost always entirely ghastly.

“Billionaires think it’s all about the boats and the planes and new expensive muscles, and it’s not,” says Graydon Carter. “This is where the Italians have it right. They’ve had a chaotic government over the last 75 years. But most of us, if we had a second life, we’d come back as Italians. They just seem to do life better than we do, with the French not far behind them. [Agnelli] was Italian, and he had a style and a charisma after the war which most billionaires these days don’t have. None of them have it, in fact.”

By the late 1990s, the world was already beginning to move away from Agnelli. Fiat’s profitability was tanking in the face of cheaper Japanese competitors, while a massive investigation into official corruption forced l’Avocatto to admit to paying out some $35 million in political bribes over a 10-year period. Far worse, however, was a double tragedy that struck the family — who began to be dubbed, for their mixture of the tragic and the beautiful, the ‘Kennedys of Italy.’

Agnelli’s only son, Edoardo, committed suicide in 2000 by jumping headfirst in his pyjamas from an overpass outside Turin. The pair had always had a fractious relationship — “Agnelli wouldn’t exactly win father of the year”, says Carter — and Edoardo was often undermined and overlooked by the patriarch. (Some people close to the family maintain Edoardo jumped in order to show his father, finally, that he had real courage.) Three years earlier, Agnelli’s nephew, also called Giovanni, and the most likely heir to the Fiat throne, had died suddenly of cancer.

"But Gianni was completely different. He had his own style..."

The double blow was almost too much for Agnelli, whose health began to deteriorate rapidly. “I want to die like an old soldier, on his horse,” he once said. But the end came far more quietly. Agnelli died of cancer in his bed at home in Turin, on 24 January, 2003. The funeral service in the city was like that of a great head of state, marked most solemnly by a sole piper playing “Silenzio,” an honorific melody to departed officers. The family shook so many hands — of workers, local citizens, dignitaries and friends — that their palms were bruised by the evening. “He was ultimately loved by the Italians, and he loved them back,” says Alain Elkann.

“I spoke to him two days before he died, because our great friend Count Roffredo was staying with me in Gstaad and had fallen out of a window trying to get to a girl’s room,” Taki says. “And Gianni called — he was blind by then, he couldn’t see much — and he asked me what happened. I said ‘‘l’Avocatto, he had taken schnuff-schnuff and he walked out of a window.’ And we laughed.” Then he stops. “But I don’t want to talk about those days now.”

Pigozzi remembers one morning in particular on the Riviera. “One day he knocked on my door very early and said: be ready in three minutes. And we went to a place that was selling lobster in St Tropez. There was this huge one. And the guy said: that one’s over 100 years old. And so Gianni bought the lobster — it was still alive — and he brought it onto the boat. And he said: okay lobster, I’m putting you back to sea — and he put it back into the ocean,” Pigozzi says. “I always liked that story.”

What is Agnelli’s legacy now, if such a thing matters, 20 years after his death? “It wasn’t just about style,” says Carter. “He was very much about substance. He left his company in reasonably good shape, and built it into an Italian colossus.”

But l’Avocatto’s real endowment feels almost more spiritual than industrial. “We’re going through a very difficult hair-shirt era right now, and Agnelli’s greatest time happened after a World War,” says Carter. “And whatever we’re going through now, when we come out of it, the world will be different. I have no idea what it’ll be like — but I think there’s a high possibility that fun might be back on the menu.”

Perhaps even that might be too meditative or weighty for Agnelli, who roared ever onwards, ever faster, fuelled by his tastes (which is to say his appetites) as much as by the events that shaped him. “I don’t much like taking stock, and especially I don’t like the past except inasmuch as it fixes our identity,” he once said. “I love the future and I’m fond of young people. My whole life has consisted of betting on the future.”

“Yes — he was always running after something,” says Alain Elkann. “He was always running after the sunshine.”

Want more from l’Avocatto? Here’s a short history of Gianni Agnelli’s incredible car and yacht collection…