Words: Jonathan Wells

The world was a different place when they made Get Carter. It was 1971, the Sixties were done swinging and the Kray Twins had just been convicted. Audiences wanted more gangster grit; more vicious violence. They wanted realism, harsh truths and stories given to them straight. And they got it. Because, fifty years ago this year — on March 10, 1971 — Get Carter was released in Britain.

From its binge drinking to its brutal killing, the Michael Caine picture punched a hole in popular culture. To the tunes of a jangling jazz trio, the British-made masterpiece follows a career-best Caine as he leaves London for Newcastle, travelling north to investigate the untimely, suspicious death of his brother. We watch as Caine’s titular Jack Carter carries out a campaign of womanising, murder and exquisite tailoring across the city. It’s harsh, lairy, crass — and one of the best British films ever made.

Half a century later, Get Carter is still influencing filmmakers. Upon its controversial release, it became a firm favourite of Stanley Kubrick; he of The Shining and A Clockwork Orange. It’s the film that inspired Quentin Tarantino to make movies. It even inspired Michael Caine himself to call his dog Carter — not as impressive an influence, admittedly, but a fun fact nonetheless.

Michael Caine and ‘Jack’s Return Home’ author Ted Lewis

Let’s start with the source material. In 1970, mere months before Caine was cast and the cameras started rolling, author Ted Lewis was typing the last letter of his latest novel; ‘Jack’s Return Home’. Audiences were clamouring for crime and Michael Klinger, a producer from London, was hunting for the seediest, most intemperate story he could find. He read ‘Jack’s Return Home’, and thought it would make the perfect window onto the British criminal underworld. So began the breakneck ten months between the film’s inception and its release.

Firstly, Klinger had to find funding. Nat Cohen, the man who had helped finance the first Carry On films ten years prior, was a producer at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. And MGM were in trouble. The film studio was shutting down its London-based Borehamwood operations — and were looking for films with slightly smaller budgets. Around £700,000 was allotted to Klinger’s Carter production, and with that he set off to find a director.

It was this decision that would impact the whole project. Rather than chasing down slick, action-proficient directors of the time, such as The Spy Who Loved Me’s Lewis Gilbert, or The Day of the Jackal’s Fred Zinnemann, Klinger turned to Mike Hodges. Hodges was a documentary filmmaker, working on current affairs series World in Action — and his only dramatic experience was with a 1968 children’s show, The Tyrant King.

Hodges was an odd choice. But he also had a way with words and a talent for screenwriting. And so, with original author Ted Lewis’ approval, Hodges signed on to both adapt and direct the film (and was paid the princely sum of £7,000 to do so). The novel didn’t specify which northern city Jack Carter returned to, so Hodges wrote his adaptation with Hull in mind. He also wrote his Carter for an actor called Ian Hendry to play. Neither choices would come to pass.

Instead, after several rewrites — the film had working titles including Bent, Here Comes Carter and Carter’s the Name — the decision was made to set the film in Newcastle. And Klinger, without telling Hodges, had already cast his lead…

Michael Caine, of course, was already hot property. Fresh off a successful run of films including The Ipcress File, The Italian Job and Battle of Britain, the London-born actor was a surprise choice for the role of the innately unlikable, brutally homicidal Jack Carter. And yet, Caine had his own, personal reasons to take on and tackle the character.

“One of the reasons I wanted to make that picture was my background,” the actor told a local Californian newspaper in 2002. “In English movies, gangsters were either stupid or funny. I wanted to show that they’re neither. Gangsters are not stupid, and they’re certainly not very funny.”

Instead, Caine pushed (he has since been credited as a co-producer) to create a more realistic, grounded screen depiction of the British underworld. He wanted more violence, more outwardly illegal behaviour — and even used his personal knowledge of criminal acquaintances to inform that stony performance.

“Carter is the dead-end product of my own environment,” Caine went on to say, “and my childhood; I know him well. He is the ghost of Michael Caine.”

And the ghost of Michael Caine made for a terrifically engaging protagonist. On set, the actor was said to exude a terrifying energy; his ultra-violent actions more abrupt, restrained and chillingly clinical than any in previous gangster films. The actor’s stand-in, the man responsible for some of the more aggressive stunts and sequences, happened to share the name of Caine’s protagonist; Jack Carter. It’s a quirk of fate, and one of many strange anecdotes from the Get Carter set.

"In movies, gangsters were stupid or funny. I wanted to show that they're neither..."

The strangest involve the actor who played enforcer Eric Paice, Ian Hendry. That’s the same Ian Hendry who Mike Hodge had written the role of Carter for. Instead, cast as consolation in a supporting role, Hendry proved a sullen, bitter presence on set — and leant genuine rivalry and tension to his scenes with Caine.

Hendry’s career had already peaked by the time of Get Carter. He had starred in the first series of The Avengers, and had even been cast as 006 in John Huston’s Casino Royale. But, by 1970, he was in bad shape physically, was drinking heavily and couldn’t conceal his envy of Caine. The night before shooting a confrontation at a racetrack, Hodges wanted the two actors to rehearse in the hotel. Hendry was allegedly so drunk and resentful they had to abandon those attempts.

The climactic chase scene (pictured above) was also affected by Hendry. A stunningly bleak, music-less affair, Hodges filmed the foot pursuit in reverse because he was worried Hendry would be too breathless to perform a convincing death scene otherwise. It was a clever impulse on behalf of the director — and, captured along the black colliery beaches of the East Durham coast, resulted in one of the most unsettling set-pieces of the film.

But Hendry wasn’t the only loose cannon in the cast. John Osborne, a playwright Hodges chose to play crime boss Cyril Kinnear, spoke his lines with such a malicious softness that the sound recordists struggled to pick up any of his audio. Bryan Mosley, a devout Catholic, Coronation Street actor and the man who beat out Bond villain Telly Savalas to the part of businessman Cliff Brumby, was so worried about the swearing and violence that he kept consulting his priest for reassurance.

And Britt Ekland, global sex symbol and the actor touted as the film’s female lead, was initially reluctant to take her third role in a row as a ‘gangster’s moll’. However, financial problems forced her to take the part — and film a mere four minutes of screen-time. But things would look up. Two years later, Ekland would go on to play a Bond girl in The Man with the Golden Gun.

It was an abnormal set — but, then again, Get Carter was always going to be an abnormal film. Director Mike Hodges and his cinematographer, Wolfgang Suschitzky, were both documentary filmmakers by trade — and they drew upon their trusted ‘real-world’ techniques when shooting. Hodges hired only documentary filmmakers for his second unit directors, and even called on local bystanders to play extras in the film.

They decided not to include car chases — so as not to draw unwanted and unfavourable comparison’s to Steve McQueen’s 1968 Bullitt (the closest Get Carter comes is a bungled getaway through some washing lines in a Ford Cortina. McQueen’s sexy flying Mustang, it is not).

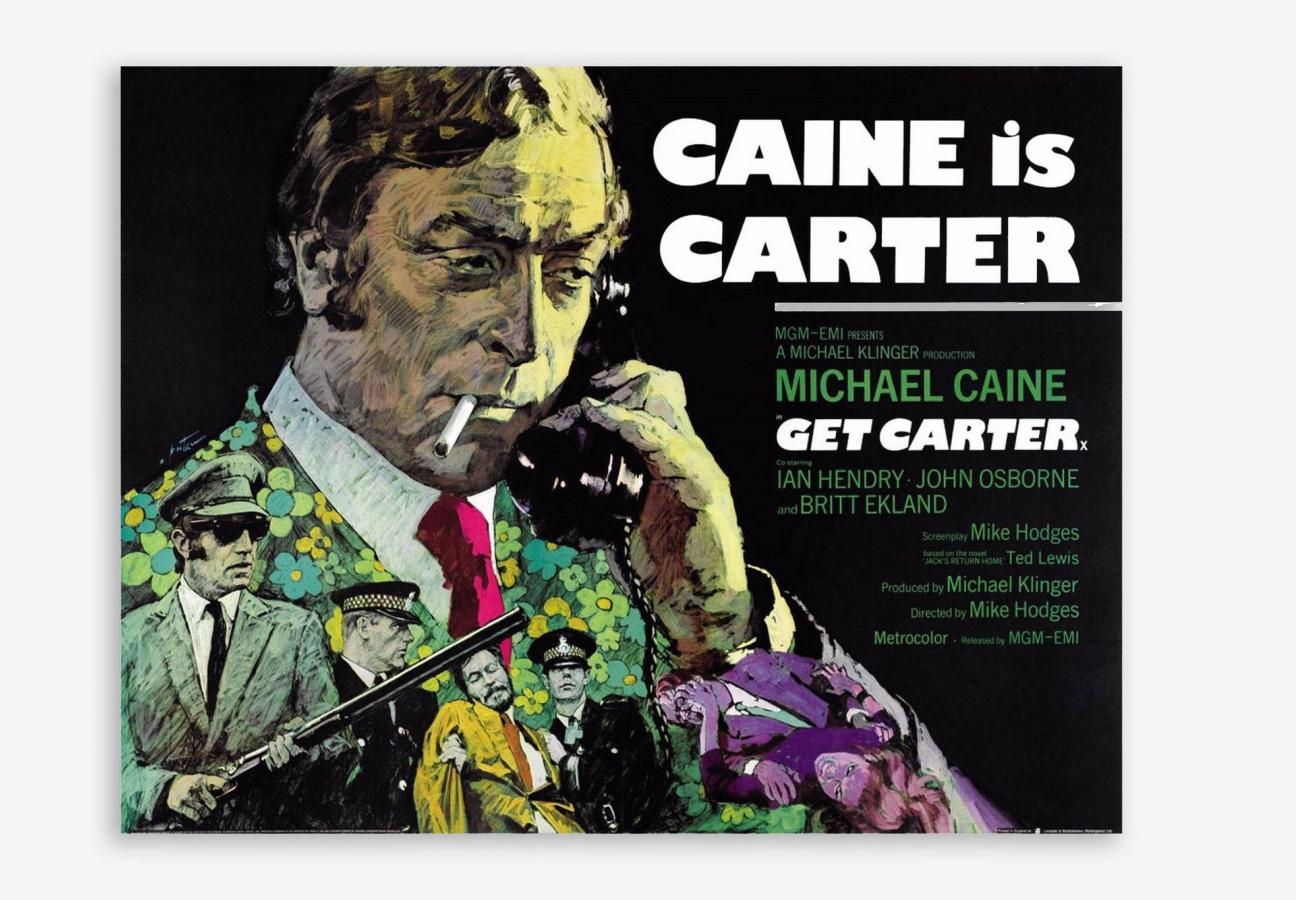

But this all added to the realism of the film. On 10 March 1971, when Get Carter was released, London bus advertisements proclaimed ‘CAINE is CARTER’, and the paying public — although shocked by the levels of violence, nudity and profanity — got their first realistic look at the grubby British underworld.

Critical response was mixed. But, over time — and thanks to the endorsement of Tarantino, Guy Ritchie and other directors — Get Carter has established itself as one of Britain’s most formidable, important films. It wasn’t until 1993 that the film was finally released on home video; over two decades after it premiered in cinemas. This upswell of public interest even led to Ted Lewis’ original book being reprinted (and a disastrous 2000 remake starring Sylvester Stallone, which we won’t further sully this celebration by delving into).

By 2004, Total Film magazine had named the original Get Carter the greatest British film of all time.

And so, to finish, a final anecdote. The enduring image of Get Carter is of Michael Caine, dressed to the nines in his three-piece suit and toting a pump-action shotgun. But this gun never actually appears in the film — and was only used for promotional photographs. In fact, even the weapon that appears in Get Carter, a double-barrelled shotgun, is never actually fired. Instead, it’s only ever used as a blunt instrument. And, as grisly as that is, it’s also befitting of the film — because, hard-nosed, powerful and deservedly enduring, Get Carter is something of a blunt instrument itself.

Want more to watch this year? Here are the films we’re looking out for in 2021…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.