Words: Jonathan Wells

Photography: Olivier Hess

“You’re not going to see a lot of robots today,” says Jonathan O’Driscoll proudly. Neatly turned out in a Gieves & Hawkes suit, it’s already the third time Bentley’s in-house customer host has brought up the importance of hand craftsmanship to the brand — and we’re still yet to make it to the production line.

But his eagerness to hammer home this messaging is hardly surprising. O’Driscoll himself worked on the factory floor before stepping into his current role, and he has 16 years of experience and expertise up his smartly tailored sleeves.

“In fact,” he continues, “the only robot on this entire production line — which has 64 stations, by the way — is the one that applies the silicon windscreen seal. The rest is all done by hand.”

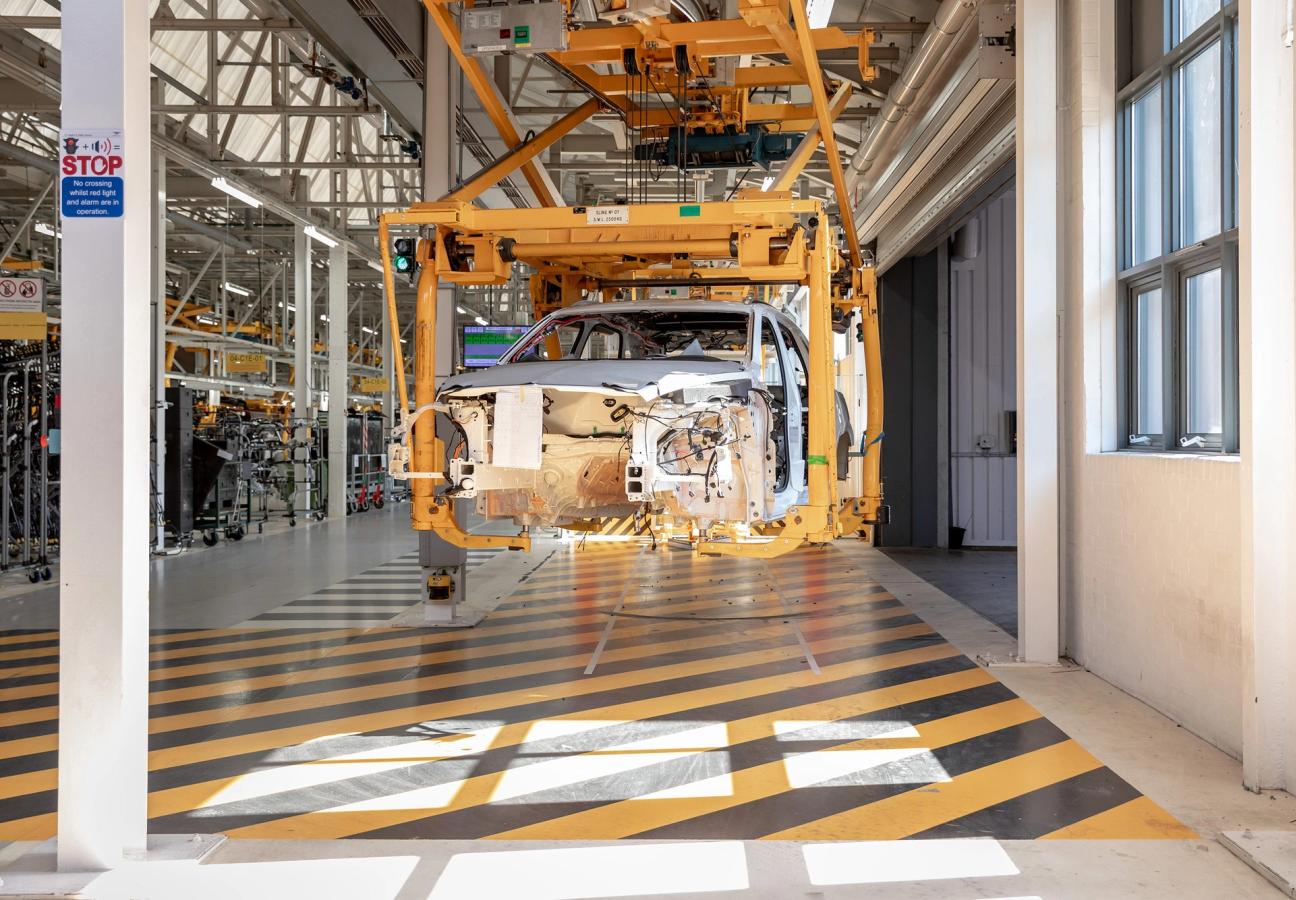

And the 64 stations are impressive. We’re standing in a huge, cavernous white hall, with Continentals at varying stages of completion stretching out in front of us. Every 9 minutes, a new car shell sails over our heads on a large rig, and begins a 2-day journey down the line. Today, O’Driscoll tells me, they hope to complete 46 vehicles before clocking off.

The noises echoing off the assembly line are loud, but not unbearable. The odd harsh squeak of new tyres does cut through you, but also heralds a new car making its way outside for the first time; embarking on its maiden cruise around Crewe — the Northwestern town where Bentley have been creating cars for almost 80 years.

And this campus, where all modern Bentleys come to life, really does feel like home for the brand. O’Driscoll calls it a big village and, thanks to a dedicated road and traffic light system, not to mention a medical centre with doctors and a dentist on the payroll, he’s not far wrong.

As a brand, the company is growing. Last year was the fifth in the company’s history during which they produced more than 10,000 cars. And, while this is an 80-acre site, Bentley owns 115 acres — ready to expand into a hybrid and electric-powered future. Part of a recent £28 million investment even installed 22,000 solar panels onto every roof; and 60% of the energy used on site is now also produced here.

Even though few robots are used throughout the factory, the assembly line feels like a well-oiled machine. The new shells, already painted in colours ranging from the popular Sequin Blue to the deep red, playfully named Cricket Ball, buzz down onto the slowly advancing floor — where they are immediately set upon by scores of single-minded workers.

By the side of the main assembly line, other annexes and production areas are also ticking over. Industrial ovens sit hot, baking wiring looms to soften the wires and make them easier to thread eight miles of electricals through the cars. Airbags are also carefully transported in bright yellow cages, given wide berths by the workers to ensure no-one accidentally sets them off.

To our right, the dashboard assembly line is hidden behind a wall of exhaust systems. Here, each dash takes 79 minutes to be built, with 10 stations adding components and veneered finishes to an aluminium frame.

"You’re not going to see a lot of robots today..."

These woods, O’Driscoll explains, are one of the luxury touches that make Bentley the brand they are. Earlier, we visited the woodshop, where master craftsmen work 24 hours a day, five days a week.

“Walnut is the most popular wood,” reveals O’Driscoll, “But all go through the same process.”

That process, he goes on to explain, begins with the root or ‘burr’ of the tree. Woods from all over the world are boiled for four days in a facility in Valencia, before being sharpened like a pencil into 0.6mm sheets. These sheets are then stored in a high-shelved, cold room at the Crewe facility — which allegedly holds £700,000 worth of wood at any one time.

From Smoked Fiddleback Eucalyptus and Hawaiian Koa, to Japanese Tamo Ash or Sequoia from the great Redwood Forests of California (three trees are planted for every one felled), these woods are then layered and pressed into veneers, before being lacquered by a machine and taken to be polished.

Jake is on polishing duty today, applying beeswax and a slight abrasive agent to a belt or wheel before buffing the matt wood to a high shine. It’s an impressive transformation, and one that will soon be installed into the car on the production line.

Back at the main assembly point, the latest Continental is lifted over a walkway. Then, before being lowered back down, fuel and air lines are channeled in and batteries fitted from underneath. These parts, O’Driscoll explains, are sourced from over 1,700 suppliers worldwide — each one the very best at what they do.

Eased back to the floor, the car sails through wheel alignment, calibration and set-up, while the red protection covers are removed and the car, as the wood was, is rubbed to a shine by a team of girls in high-vis jackets. The polishing here is approached with the same dedication and delicacy as the veneers — with it taking nine hours to hand-polish just one wheel.

The interiors, too, begin to take shape. Each Continental is upholstered in 10 Scandinavian bull hides; male leather being stronger, and the altitude and remoteness protecting against insect bites and barbed wire fence scars.

Despite these precautions, a team of dedicated workers still pore over the imported hides with chalk — poised to circle scars, imperfections and growth lines before cutting the leather into the patterns stitched together by the upholsterers.

Primed behind banks of custom-engineered sewing machines, trained seamstresses keep their eyes on overhead LCD screens reporting numbers of completed headrests and seat backs. Rachel, sitting stitching, explains that each seat is like a jigsaw — and more pieces of leather are joined together as the covers are passed back through the rows of workers.

Once assembled, Ange inspects colour and stitching to ensure the seat leather is ready to be upholstered onto the seats. It’s a meticulous job; you can find 712 stitches in each diamond of quilting — and 4,760 in every headrest’s Bentley logo.

But, once Ange approves, these covers join the rest of the components to be fixed into and onto the seats. Transported across the hall in large green metal boxes, the wires, fixtures and fittings are built together on their very own production line — with 32 cars’ worth of seats being built every day.

“The last GT was very basic in comparison to these seats,” laughs Tom, his fingers flitting over a mass of multi-coloured wires. “There’s sports mode, space sensors, a lot more to think about. And we move very quickly.”

Each worker on the seat production line has just five minutes to complete his task before the seat must move on. And the final step, before the seats are fitted into the car, is to give the leather a good iron.

“We bought posh irons to do this with,” says Tom, “before we realised that normal irons do the job just as well.”

Once the seats make their way over to the main assembly line, and are fitted into the shells, the cars become close to completion. But first comes the testing — and an extensive testing process it is.

“The cars are subjected to 505 checks during this last section of assembly,” explains O’Driscoll. “And, if they fail just one of these examinations, they roll back up the assembly line for fixing. Not that many do. Workers have to sign every part of the car they touch during the production process, so they’re always extra careful. You don’t want to be identified as the person who’s messed up!”

"Workers have to sign every part of the car they touch during the production process..."

Of these 505 checks, an extensive electrical testing station sits to our left, with the excitingly named ‘Monsoon’ testing station sitting to our right. Here, the cars are subjected to jets of high-pressure water to ensure no errant drips of drops make their way into the lush leather interior.

The paint inspection test is also an important part of the examination process. Exceptionally bright to look at, 25 rigs of high-powered lights beat down on the cars’ bodywork, their high-wattage scrutiny exposing any nicks, dents or flaws in these newborn Bentleys.

And, by the door, a rolling road provides one the last test. Here, the cars are “thrashed” at maximum revs for an scarcely credible 7 hours. That’s the equivalent of driving over 1,000 kilometres.

With that, the cars go squeaking out of the door, primed for their first foray onto the roads. And, given they’ve passed so many stringent tests to make it out of the factory, they rarely return. For, as O’Driscoll emphasised at the start of the assembly line, almost every part of the production process is completed by the skilled hands of the company’s 4,000 workers.

And, as he’s also keen to remind me: “Bentley has the best”.

Want more Bentley? Read our review of the new Continental GT Convertible…