Words: Jonathan Wells

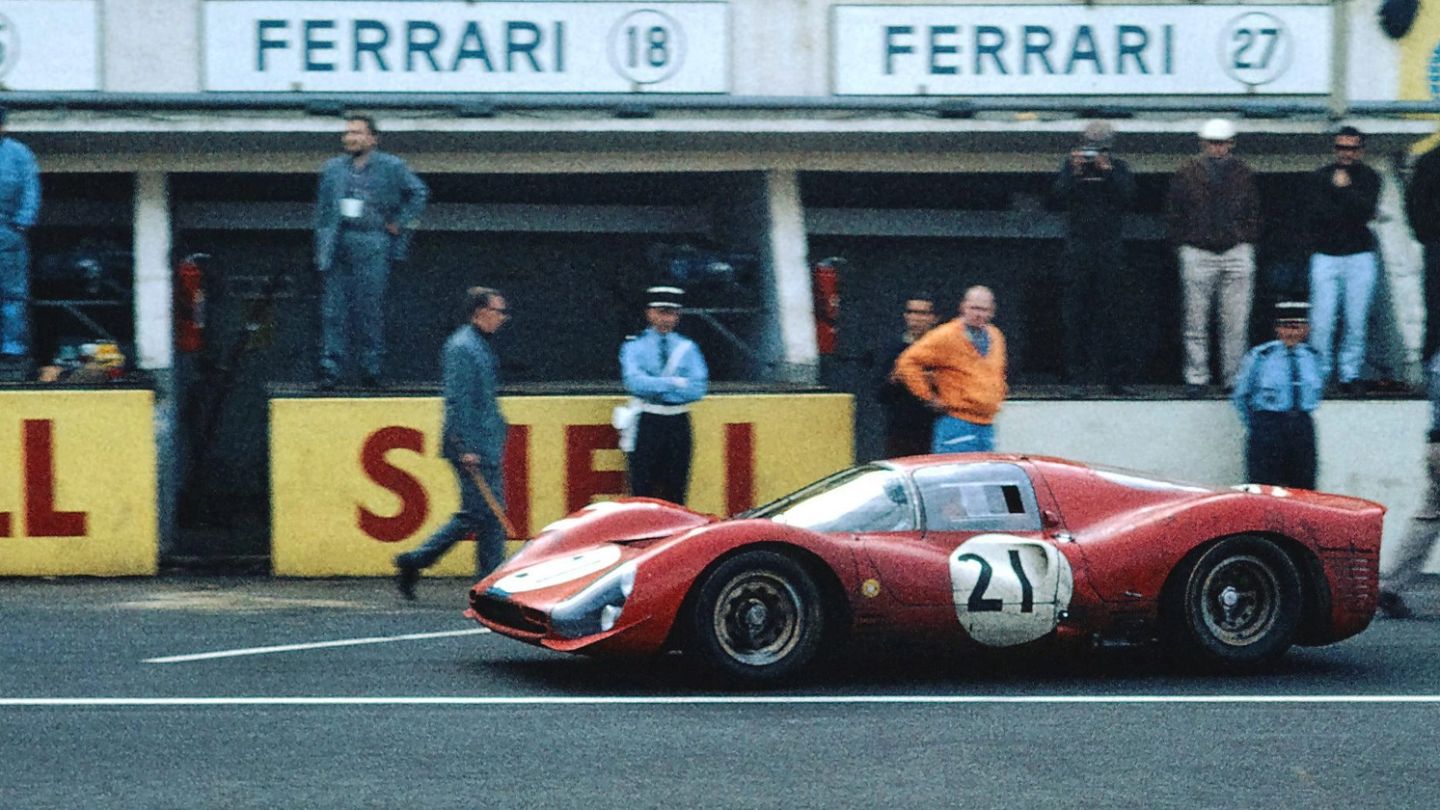

It is 1966. Tyres are screeching, the crowd is clamouring and thunderous engines are hurtling their way around the track. The night is black, the rain heavy and the world’s most powerful cars are straining at their cambelts to take the chequered flag. Some of the most celebrated drivers ever to compete are sweating through their race suits; putting their careers, reputations and lives on the finish line to come up victorious at Le Mans’ 34th Grand Prix of Endurance.

It’s one of the most important events in motorsport history. And, for this one night in the mid-1960s, the Circuit de la Sarthe burned with competition. It was a tyre-streaked, petrol-drenched, adrenaline-fuelled pressure cooker of a contest — and one that shifted international racing into a dangerously high gear. Over half a century later, a Hollywood film last year told the story of that race; examining the rivalry of Ford v Ferrari, and telling the fraught tale of out-engineering and one-upmanship that saw Ford’s GT40 finally snatch victory out of Ferrari’s fierce Italian jaws.

But this race was memorable for more than its outstanding title fight. 1966 was also the year the immortal Jacky Ickx took to the fabled circuit for the first time, and the first race for Frenchman Henri Pescarolo — who went on to compete in the race a record-breaking 33 times. It was an event charged with fiery collisions, dawn downpours and blown engines. It was as dangerous a motor race as you could imagine — or, in other words, just another 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Image courtesy of Klemantaski Collection

As the oldest endurance race in the world, Le Mans has been attracting the best drivers and manufacturers in the business for almost 100 years. And, unlike most motor races, where competitors push to cross the finish line first, this grand prix of endurance and efficiency sees the top title go to the car that covers the greatest distance over the course of one supercharged day. As such, the race hinges as heavily on intricate equations and tactical driving as it does on sheer, unflinching nerve.

And it’s been this way since the very first race. In 1923, after the Automobile Club de l’Ouest drew up the rules of the race, a flurry of excitement immediately whipped the event up into a phenomenon. Acetyline floodlights were borrowed from the French Army to line the corners of Arnage and Pontlieue. Gravel, dirt and tar were shipped in to seal the roads, and radios were tuned to a special broadcast of classical music — from the Eiffel Tower — to score the impending drama.

And drama there was. When the tricolour fell — the French flag waves at the start line of Le Mans, not the traditional green flag — the inaugural race set the pace for the thrills and spills of years to come. Captain John Duff and his Bentley took the brunt of the difficulties. Early on, an errant stone took out one of his two headlamps. And, as the team hadn’t brought a spare, they had to push on into the night regardless. After a close miss with an 11-horsepower Bignan Desmo Sport, Duff’s Bentley was once again struck by gravel — and his fuel tank punctured.

Racing intuition prevailed, and the Canadian — who had been gravely wounded during the First World War’s Third Battle of Ypres at Passchendaele — left his car and ran the four miles back to the pits to alert his co-driver, Frank Clement. Clement slung two cans of fuel over his shoulder, took a cork to bung the tank and commandeered the local gendarme’s bicycle. He cycled to the stricken car, effected the repair and the pair won the race. The Bentley Boys later returned the bicycle.

Just as the race secured its status as the most dangerous, exciting motorsport event in the world — and one leg of the Triple Crown of Motorsport, alongside the Indianapolis 500 and Monaco Grand Prix — World War Two imposed an unwelcome 10-year hiatus on Le Mans. Yet, when the fiery competition roared back into life, it did so with more ferocity than ever.

Bugatti and Alfa Romeo pioneered aerodynamics; sculpting their coachwork to shave off precious seconds on the Muslanne Straight. Ferrari blazed onto the scene, taking its first title in 1949. And then, in 1953, came one of the most queried, questionable and downright ridiculous stories in the race’s history.

"When the fiery competition roared back into life, it did so with more ferocity than ever..."

It was the day before the race, and Jaguar’s revolutionary C-Type — driven by Duncan Hamilton and Tony Rolt — was the out-and-out favourite to win the race. But, ‘Drunken’ Duncan Hamilton revealed — in a story that many consider to be embellished — the pair were disqualified over an incorrect racing number. The car, for all its groundbreaking engineering — among other things, it was the first to use disc brakes at Le Mans — would not race.

And so it was that the men took their stiff upper lips to the bar for a nightful of stiff drinks. But, as their blood alcohol levels rose, so did the resolve of steely Jaguar team manager, Lofty England. England persuaded the powers that be to allow the Jaguar to race — giving him the unenviable task of reviving his drivers. Hamilton was to start the race, and was offered coffee to sober himself up. But, according to the boisterous Irishman, coffee made his arms twitch — so he opted for brandy instead.

Fortunately, the Jaguar team managed to fend off their competition as well as they did their hangovers. And, despite topping up with cognac during pitstops, and Hamilton having a pigeon smash into his face at 150mph, spectacularly breaking his nose, the two went on to win the race.

Admittedly, luck doesn’t always come to Le Mans. Just two years after Hamilton took the trophy, a disastrous crash claimed the lives of almost 100 spectators. It was 1955, and the race began drenched in optimism. The odds were split three ways between Ferrari, Jaguar and Mercedes-Benz and the racers and spectators alike were poised for a true spectacle.

Unfortunately, when Mike Hawthorn pulled in front of Lance Macklin’s Austin Healey, and Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes-Benz careened into Macklin’s back, Levegh was launched into the air, soared over a protective ridge and smashed to a standstill in the pool of packed spectators. It exploded, hurled flames and debris in all directions and killed 83 spectators. 120 more were left injured. Hawthorn, rather distastefully, carried on racing, claimed victory — and was even pictured swigging Champagne on the winner’s podium.

On a side note, the first televised instance of Champagne being sprayed from the winner’s podium also took place at Le Mans. In 1967, Ford’s Dan Gurney was so elated by his win that he shook his magnum of Moet all over the assembled crowd. Life Magazine photographer Flip Schulke caught the moment on film, and Gurney gifted him the empty, autographed bottle as a thank you. Schulke turned it into a lamp, used it for many years — and returned it to Gurney decades later.

But, in the years that followed Hawthorn’s misjudged Champagne celebration, the shadow of the 1955 disaster loomed large. And, although safety measures were extensively revised, one dangerous tradition remained. The Le Mans-style start, where racers would line on the opposite side of the track, wait for the flag — and then race to their cars, jump in and tear away as quickly as possible, had long been a signature of the endurance race.

However, in 1969, Jacky Ickx staged a one-man protest against the practice. Ford’s golden boy had recently lost his teammate, Willy Mairesse, and was mindful of the dangers of the tradition. Rather than running, he walked slowly to his car — almost being hit in the process — and took his time to strap on every one of his safety harnesses. Seconds later, before Ickx had even got going on a race he would eventually win, British gentleman-driver John Woolfe lost control of his twitchy Porsche 917. He hadn’t strapped in, was thrown from his exploding car and killed immediately.

Death and petrol have always gone hand in hand at Le Mans. And, despite Ickx’s appeal for safety, the years that followed saw many lose their lives on the fabled track. In 1972, Swede Jo Bonnier launched his Lola Cosworth into the trees by the Indianapolis bend and died on impact. Andre Haller skidded his Datsun at the Mulsanne Kink in 1976, incurring fatal chest injuries. And, in 1981, Jean-Louis Lafosse killed himself and two marshals when his Rondeau veered into a barrier on the main straight and was thrown across the raceway.

John Sheldon, a British racing driver, almost joined this list in 1984 when his Aston Martin flew into the undergrowth off the Mulsanne Straight, crashing at almost 200mph and starting a forest fire. A marshal was killed, but Sheldon — who never remembered the accident — scrambled free with mere burns. And his miraculous escape kicked off a spate of near-misses.

The following year, Dudley Wood destroyed his Porsche 962 in practice — crashing so hard that he cracked its engine block. He survived. As did John Nielsen, who flipped his Sauber-Mercedes at 220mph over the Mulsanne hump, landing it upside down on the asphalt. And Price Cobb, who managed to escape the wreckage of his crashed Porsche in 1987, did so seconds before the fuel tank exploded.

Although the 1980s clearly provided more than its fair share of incident, including Roger Dorchy clocking the fastest ever speed of 253mph during the 1988 race, little can eclipse the glamour of the 1970s, when movie stars were drawn to the high octane excitement of the Circuit de la Sarthe and the Le Mans legend shifted into overdrive.

In the months leading up to the 1970 race, Hollywood actor Steve McQueen had been lobbying Warner Bros to produce a film titled Day of the Champion — the story of an endurance racer at Le Mans. The studio passed, sold the picture to Cinema Centre Films, and production began on the newly retitled Le Mans. Unfortunately, the new studio was uncertain about casting McQueen as the lead of his own passion project, and even tried to halt production to coerce Robert Redford into the main role. McQueen found out, and eventually forewent a salary and any percentage of the profits to get the film made.

"In the 1970s, movie stars were drawn to the high octane excitement of the Circuit de la Sarthe — and the Le Mans legend shifted into overdrive..."

Production was no smoother. Fresh off a second-place ranking at the 12 Hours of Sebring, McQueen wanted to drive a Porsche 917 in the race with Jackie Stewart as his co-driver. Much to his chagrin, McQueen’s insurance providers blocked this proposal. And, although rumour has it that McQueen concealed his identity to drive in the race — finishing ninth in his own Porsche 908 — the likelihood is that any race sequences shot on the day were of German Herbert Linge at the wheel.

Not that McQueen escaped any scandal. Production continued around the Circuit de la Sarthe for weeks after the race and, one stormy night, the actor crashed and rolled his own car in the rain — carrying his personal assistant and the film’s female lead as passengers. So as not to cause a stir, McQueen didn’t call an ambulance, and instead decided to steal a car from a nearby French farmhouse. The farmer spotted him, threatened him with a shotgun and left the actor with one more unsavoury on-set story. In fact, McQueen was allegedly so disenchanted after production wrapped that he didn’t even attend the film’s premiere; and never raced a car again.

Despite the ‘bloodbath’ — McQueen’s own description — of Le Mans, other actors found themselves drawn to the track. Like McQueen, James Garner and James Coburn, Paul Newman was a keen racing driver — and he took his rain-soaked swing at the endurance race in 1979. Ironically, given the turbulent weather, the Porsche 935 entered by Newman and his driving partner, Rolf Stommelen, was liveried up with exotically coloured Hawaiian Tropic decals. But, through the rain and a 23-minute-long pit stop caused by a stuck wheel nut, Newman stormed to an impressive fourth place ranking — in a field of 55.

In the years since, no celebrity driver — from Patrick Dempsey to Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason — has managed to come close to Newman’s accomplishment. The Jackie Chan DC Racing Team, yes that Jackie Chan, cleaned up second and third places in 2017, but the actor was nowhere near the driving seat. Even more minor celebrities, such as Mark Thatcher, son of Margaret, have had unsuccessful cracks at the race — Thatcher achieved a DNF in 1980, two years before he was to go missing during an attempt at the Paris-Dakar Rally. But that’s a story for another time.

This story, of Le Mans, is rather one of superstars and socialites; of unplanned pitstops and pre-race Champagne. It has evolved from an event of pluck, derring do and petrol-powered peril, to one of science and calculation. Indeed, this year, Toyota clocked 385 laps to claim victory — 257 more than Captain John Duff and the Bentley team completed to seize victory in 1923.

Countless innovations — from turbocharging and biofuel to aerodynamic styling cues — have filtered down from Le Mans cars to production vehicles, the enduring tales and achievements of entrants past still inspire modern racers, and the 24 Hours of Le Mans still spends one rip-roaring day a year earning its place in the Triple Crown of Motorsport. With a century of competition on the horizon, there is only one certainty for this nerve-testing, blood-tingling, death-defying race: it will endure.

Looking for more 1960s motoring icons? The McLaren Elva is a retro racer reborn…

Join the Gentleman’s Journal Clubhouse here.