The high-end crisis managers who fix the unfixable

Whether it’s drama in the boardroom, the bedroom, the schoolroom or the courtroom, when the reputations of those in the 0.1% are on the line, these are the people who answer the call...

- Words: Harry Shukman

- Illustrations: Claudine Derksen

They say hindsight is a wonderful thing, but it shouldn’t take a clairvoyant to realise that giving a no-holds-barred interview to trash your own customers was probably a bad idea. In the league of PR disasters, few will have messed up more in this regard than David Shepherd, the brand director of Topman, who told a magazine in 2001 that the people who purchased his designs were beer-swilling “football hooligans”. Speaking to a trade publication called Menswear, Shepherd laid into the one demographic he was not supposed to insult. Why did Topman not make smart clothes? “Very few of our customers have to wear suits to work,” he explained, citing two exceptional circumstances. “They’ll be for his first interview or court case.” Uh oh! The response from the business world was unforgiving. “Retail suicide,” said one marketing expert quoted in the press. “Corporate kamikaze,” quipped another. “This isn’t very clever,” judged a third.

In the wake of Shepherd stuffing his feet deep within his oral cavity, Topman’s PR team swung into action. Fearing a repeat of the Gerald Ratner debacle — a jewellery tycoon who ten years earlier joked that his merch was “total crap” and tanked his business — crisis managers moved to put out Shepherd’s fire. Behind the scenes, it must have looked grim. What a dunderheaded thing to say! But Arcadia Group — the high street giant that owned Topman — started briefing journalists that their brand director was a season ticket holder for Queens Park Rangers, a top lad who loved to sink pints and hit the clubs. “He uses that to monitor who the customer is,” the company optimistically said. “Topman is a brand that has a very strong laddish element and David is the embodiment of that.” Amazingly, it seemed to do the trick. The business lived to fight another day, and Shepherd kept his job. Scandal over.

Part of the one percenter’s arsenal of staff today, among the estate managers, private chefs and personal assistants, is the crisis manager who is prepared to deal with a Shepherd-grade meltdown. Sometimes they work in-house as part of a communications team, sometimes they are hired as freelancers on extremely short notice. Their job? To fix the unfixable and solve the unsolvable, to arrive at a stinking pile of corporate mess and do their best to clean it up. They are the guys who get going once the going gets tough: think The Wolf from Pulp Fiction but with a Harvard MBA. These are boardroom commandos armed with power ties and PowerPoint who parachute into disaster zones with a mission to pacify. In the TV show Succession, they are characters like the unscrupulous Karolina, the dry-wit Hugo, and Ratfucker Sam. Crisis managers are probably not the sort of people you would like to meet in a dark alley, but ones who, without question, you want on your team when a senate investigation looms, or you are about to be arrested for securities fraud.

Amber Melville-Brown

So who are these people in real life and what are they like? If you have a problem, if no one else can help, maybe you can hire Amber Melville-Brown. She is partner and global head of media law at the New York office of Withers, with a particular focus on reputation management. Melville-Brown has a supreme talent for unfucking disasters, and like the best of her peers, an Olympic tolerance for cortisol. “I operate in the concrete jungle,” she says. “But I take a leaf out of the natural world survival kit when considering how best to protect my clients. If you stumble across a mountain lion, you look it in the eye and stand your ground; should you cross the path of a bear, you keep your eye on it and keep your cool; if a crocodile approaches with you in its sights, you get the heck out of there — fast. In the case of a client crisis, knowing your enemy, understanding the landscape and acting appropriately is crucial.”

Truth can be stranger than fiction, and a lot of the crises that Melville-Brown has had to deal with would not have passed the sniff test had they appeared as plot lines on Succession. “I’ve advised numerous crisis clients over the years facing harassment by third parties,” she says. “Disgruntled former employees seeking revenge for a perceived slight; spurned lovers wanting their pound of flesh after the relationship has ended; anonymous parties with unknown motives causing havoc from afar.” One of her ultra-high net worth clients went to a bar on a business trip, picked up who he naively believed were “two lovely young ladies”, and took them back to his hotel room. Behind closed doors, they “proceeded to drug him, photograph him and attempt to blackmail him”. Poor guy, although also: poor blackmailers, because then Melville-Brown got to work. “On occasion, the big guns of law enforcement are the right choice,” she says by way of cryptic explanation.

In a case reminiscent of Fatal Attraction — although without the bunny boiling — one of her clients was hounded by a former lover who threatened to expose their affair to his wife, family and colleagues. Big mistake. “Three months of careful research — into her jurisdictional whereabouts, her professional status, her state of mental health — preceded a carefully planned salvo to our antagonist,” Melville-Brown says of her response. She sent what she describes as a “sensitively drafted cease and desist letter”, which was presumably comparable to one of those leaflets the American air force used to drop on towns before bombing them to smithereens in World War Two. It worked. Three hours later, the harassment ended when the client’s ex-mistress agreed to break off contact for good.

No two crises are alike, Melville-Brown says, and the circumstances that lead to her hiring can vary enormously. However, they tend to involve “dramas of the boardroom, the bedroom, the schoolroom and the courtroom, with sex, commerce, children and litigation issues fertile ground for a crisis”. She adds: “A crisis can happen to the best, and the worst of us, from stars of the silver screen, stage and stadium to private persons and regular Joes, from multi-million-pound international organisations to start-ups and family businesses.”

Each mess may have its own unique smell, but according to Erik Bernstein of Bernstein Crisis Management, who is based in Los Angeles and operates across the US, solving crises is extremely hard work. If a company is ablaze, there is typically more than one fire that needs putting out. “It won’t be unusual to have two or three crises on the same day,” Bernstein says. Another difficulty — as if there weren’t enough — is that the route out of a mess is rarely straightforward. Crises have a funny knack of taking two steps forward and an unwanted one backwards due to company gaffes. “It is tremendously common for there to be a loose cannon in any organisation,” Bernstein explains, referring to senior executives saying or doing something they shouldn’t to inflame the crisis further and give it another round in the news cycle.

There is a long and forever expanding list of loose cannons who, in a second, have undone the hard work that Bernstein and his peers pull all-nighters to avoid. The textbook example familiar to all crisis managers features the hapless Tony Hayward. Back in 2010, when BP caused one of the largest environmental disasters in the history of the planet — the Gulf of Mexico oil spill — Hayward, the company CEO, took a weekend off to go sailing in the uncontaminated waters of the Isle of Wight. It was not a good look, compounded by a disastrous interview that he had given a few days earlier, seemingly oblivious to the coastal communities the oil had ruined and rig workers who died. “I’d like my life back,” Hayward complained. Academics have since published papers in prestigious research journals that study just how much these five-and-a-half words ruined the reputation of Hayward and his company.

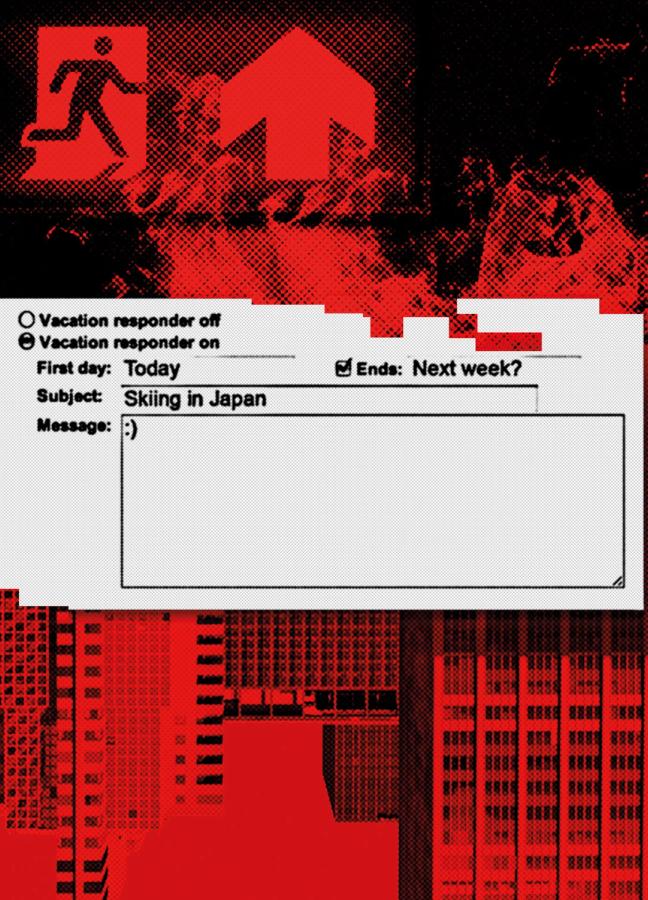

There are plenty of other villains who now form part of crisis management history, and a lot of them stem from the bad old days of the financial crash. Like in 2008, when Jimmy Cayne, the chief exec of Bear Stearns, went to Nashville to enter a bridge tournament while his bank was going down the toilet. Or in 2009, when Tim Wheeler, the ex-boss of the commercial property group Brixton, went on a skiing holiday to Japan as his firm was staring down the barrel of insolvency. Ditto the CEOs of General Motors, Chrysler and Ford who arrived in Washington, D.C. to beg for a $25 billion bailout in 2008 having swanned in by private jet.

Crises are often hardest to manage when clients face criminal proceedings. Frazer Rice, president of Wealth Actually LLC, a New York company that specialises in crisis management, has had to deal with his client’s impending drink driving conviction. Other clients have been done for assault and even more serious crimes, he says. In these cases, a crisis manager has to prepare for the worst, including getting clients ready for a prison stint.

In those instances, when passions are lying high, does Rice ever have to put up with bad behaviour typical of the Roy family in Succession? “The personalities can get prickly,” he says, diplomatically. “Money as a general rule amplifies who people are down at the core. Add onto that stress and the threat of loss, people’s emotions can get the better of them and they can snap.” Most crisis managers tend to agree that they must expect — and accept — a certain degree of yelling and hostility from their most beleaguered clients. “I have a deep reservoir of patience and empathy,” explains Rice. “I can problem absorb a lot of arrows when clients are in tough spots. But if someone is being unreasonable, you shouldn’t put up for it forever just because someone has a ten-figure balance next to their name.”

Client outbursts tend to be rarer and much less funny than in Succession (“They call him meth-head Santa because he rarely delivers”). Melville-Brown says in the private client world, there are fewer “vocal hand grenades” than on TV, although most crisis consultants will have had to brush off some shrapnel in the course of their careers. She recounts a client who learned that the discovery procedure in English courts meant the disclosure of private information: “I reeled under the punches of a Shark Tank-like ‘you’re &#$$^& fired!’ several times during the litigation — each time retracted, if not recanted — while managing to uphold my dignity and comply with my professional obligations. It is never acceptable to shoot the messenger, let alone to do so in machine-gun utterings of four-letter words, but that is not to say that it doesn’t happen.”

That may be because ultra-high net worth individuals and C-suite goons depend on crisis managers for survival. They might kick and scream, but they also need people like Meville-Brown, Bernstein and Rice to yank them out of the corporate quicksand they fell or willingly jumped into. Referring to himself as “the outside guy with the briefcase”, Bernstein is the gentleman who shows up in the darkest hour and gets to work. His recent jobs include assisting a famous food producer whose secret recipe was stolen and held for ransom by hackers, and a major contractor accused of swindling government money that faced criminal proceedings. He often meets his clients when they are in a state of high anxiety and knows they want to see a smooth operator to deliver them from evil. “If I’m going into a boardroom I need to be in a fairly sharp suit, hair done, looking professional,” Bernstein says. “Body language and tone is big, given we do media training and prep. I have to walk my talk. I can’t sell someone on my ability to deal with the media if I look like a mess.”

Having arrived and made his first impression, Bernstein will then deliver one of his killer lines that lets his clients know they are in good hands. “Something I tell people all the time is, ‘I know this is unusual for you, but I do this every single day,’” says Bernstein. “The roof being on fire is my bread and butter.” Crisis managers fulfil an unusual, nebulous role. It’s partly being a spin doctor, partly a fixer who tries to make problems disappear. But a key part of the job is also pastoral: a crisis manager needs a good pair of ears and a reassuring shoulder to cry on. “It’s not unusual for a client to call in tears,” says Bernstein, “particularly if they’re very emotionally attached to what has occurred. We have to recenter people very often so we can focus on what is happening. A hundred people tweeting something awful at you feels bad but it’s not necessarily a crisis.”

So after looking the part and listening to his clients pour their hearts out, what does Bernstein actually do? Like some Soviet physicist with a Geiger counter, he has to find out just how compromised his client’s nuclear reactor is, so the damage can be contained. “Everyone is on the edge of their seat when things first break,” Bernstein says, speaking about a hypothetical company facing a weapons-grade crisis. “There is a lot of uncertainty. Part of our role is coming in and accurately predicting the next couple of things that will happen and describing the curve of a crisis and what we do to keep that flat.”

Crisis managers are in some ways reminiscent of characters in a Christopher Nolan movie: they have creative, strategic brains plus the willingness to get their hands dirty, although to the extent of stabbing an enemy in the eye with an HB pencil. Devon Blaine, head of The Blaine Group veteran crisis management firm in Beverly Hills, says she has to master both high and low in her line of work. Back in 2007, she was hired by a company called ChemNutra that was in the firing line for supplying contaminated wheat gluten from China to pet food manufacturers in the US, leading to a slew of dog deaths. Blaine’s involvement may have saved the owners from prison.

Amid the all-night discussions with lawyers about crafting a game plan out of this fiasco, Blaine also had to worry about much more granular details. One evening, she took a call from her client in Las Vegas who was frantically telling her: “There’s a camera crew outside my building! How am I going to get out of here?” He was bleary-eyed, dressed down in shorts and a t-shirt — in no condition to appear on TV. Blaine sprang into action. “We strategised how to get him out of the building without getting ambushed,” she remembers, dispatching the CEO’s wife to bring him a suit in case he was ambushed by the press pack. Next, she enlisted a junior employee of the business to step outside and embroil the camera crew in a long and tedious background briefing. While the reporters were distracted, the CEO sneaked away. “I always look at that — an escape route out of the office,” says Blaine.

David Shepherd

Resilience is everything in this business, particularly as crises come in — as Melville-Brown puts it — with the unexpectedness of “morning fog ”. Accepting the loss of evenings and weekends is a prerequisite for success in crisis management. “It’s very difficult to take time off in this field,” Bernstein says, adding that “crises have a funny way of breaking on a Friday evening”. His wife has a habit of taking a photo of his empty chair at restaurants each time he has to duck out to take a call. “Luckily she has a good sense of humour about it.” The same goes for Melville-Brown. “I’ve missed more dinner parties than most people have had hot dinners,” she jokes. “On one occasion I spent an entire Saturday evening outside in the restaurant lobby while my friends tucked into starters, entrees, dessert and after-dinner coffee, while I was wrapped up in conversations with a tabloid newspaper lawyer seeking to explain some misunderstandings and misinformation, and thus to avoid a crisis the following day of horriffic headlines and erroneous accusations.”

The money certainly helps. A typical hourly fee for a freelance crisis consultant is $500. Agencies can bill twice as much, even up to $1,200 per hour. When your client is howling and tearing their hair out as the feds confiscate their private jet and freeze their assets, when the FBI are issuing a search warrant for their offices and when you’ve got every journalist in the country ringing you up, demanding your principal’s head on a spike, the thought of the paycheque is probably one way to keep cool. Each of them deal with the stress in different ways: Bernstein pumps iron and does breathing exercises. But a veteran like Blaine says she has no problem with keeping her head. “I’ve never had an issue staying composed while other people are losing it,” she explains, echoing Rudyard Kipling ’s famous lines from If. “That’s to my advantage.”

This feature was taken from Gentleman’s Journal’s Summer 2023 issue. Read more about it here…

Want more long-reads? We go inside the many lives (and lovely office) of film producer Charles Finch…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.