Words: Jonathan Wells

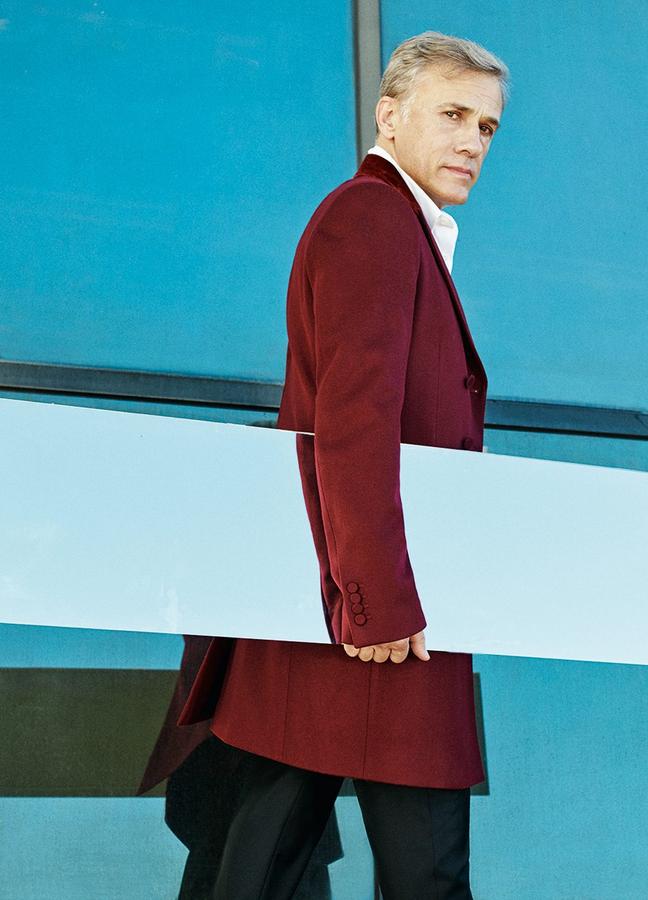

Photography: Gavin Bond

Christoph Waltz is a devil in the City of Angels. The Austrian-German’s hold over Hollywood began when Quentin Tarantino cast Waltz as Nazi SS-Standartenführer Hans Landa in 2009’s Inglourious Basterds.

Three years after this Oscar-winning turn, Waltz once again stormed Tinseltown and picked up a second Academy Award for his role as bounty hunter Dr King Schultz in Django Unchained.

And, a further three years after that, the actor finally achieved world domination when he became the latest incarnation of James Bond’s arch-enemy, Ernst Stavro Blofeld.

Two years ago, the man who redefined villainy moved to Los Angeles for good. And, today, he is sitting opposite me – coldly charming, quietly composed, and dissecting a Santa Monica salad.

“Cut-throat,” considers the actor, rolling a cranberry up the side of his bowl. He delivers the word with a whisper, and it’s almost chilling to hear it play across his lips. But Waltz isn’t describing a grisly crime or scheme – but rather the US film industry. “Filmmaking is a regular American business,” he continues, pausing to take a measured sip of water. “So of course it will be cut-throat at the top. This is America – there’s no way around that.”

And throats have been cut. From the manipulative Cardinal Richelieu in 2011’s The Three Musketeers, through campy supervillain Chudnofsky in The Green Hornet, to the corrupt Captain Léon Rom in last year’s The Legend of Tarzan, Waltz has inflicted considerable wrath on all manner of characters. The actor’s filmography reads less like a resume; more a rogue’s gallery. But, Waltz smiles, he is very good at bad.

“I think it has a lot to do with my appearance, my age, my aura, my physiognomy,” Waltz deliberates, skewering a salad leaf on his fork. “And they don’t just cast me as some random bad guy.”

He pauses, levelling the lettuce at me across the table. “In fact, there’s no such thing as a random bad guy. Very often, Hollywood deals with villains in a very one-dimensional way, which can make them seem generic and boring. But they rarely are. I’m yet to play a boring role – why would I? And that’s because I don’t focus on, or study the character before I take a role. “Instead” – whispers Waltz, narrowing his eyes – “I study the story.”

And Waltz has told many tales. From Big Eyes, the biographical story of infamous American plagiarist Walter Keane, to Horrible Bosses 2, a comedy romp in which Waltz’s greasy investor grabs money and has an actual moustache to twirl, the actor’s eye for a story is at once varied and villainous. But, although the roles always err on the wrong side of the law – and morality – Waltz isn’t worried about being forever typecast as an antagonist. Instead, he seems to almost relish the reputation, and has self-confessedly embraced his inner darkness.

“Good casting is typecasting,” elaborates Waltz. “The casting has to be right. That’s why I don’t believe in ‘schools of approach’. In the end, it’s all branding.

“There’s no such thing as a good actor or a bad actor. There’s just right or wrong. Some actors may be more flexible, so they’ll be right for more roles than others. But you shouldn’t be cast if you’re not right. In this way, typecasting is essential.”

"There’s no such thing as a random bad guy..."

Waltz falls silent, and his face contorts slightly. It would seem as though he’s not altogether happy with the last point he made – and this irritates him.

“That doesn’t mean that you have to play the same character every time,” he continues tentatively, tapping pepper from the cellar with his forefinger. “Not at all. But you can’t be broad as an actor – because if you’re not seen as a particular type of actor, or not cast right, then you have no chance of ever getting a foot on the ground.”

For an actor, surely the greatest endorsement of their villainous skills is when Bond comes knocking. For Waltz, this came to pass in the shadowy shape of 2015’s Spectre, when he followed in the footsteps of other great actors – including Javier Bardem, Sean Bean and Christophers Walken and Lee – by going toe-to-toe with the superspy. But, despite hitting the pinnacle of evil, Waltz reveals that we won’t see him slipping back into the Nehru jacket any time soon.

“I don’t think I’ll be back,” Waltz says, with a flicker of disappointment. “Daniel [Craig]’s doing the next one, but so far I’ve been told that I’m not. I didn’t die in the last one, but I think that’s more to keep the idea of S.P.E.C.T.R.E, this big criminal organisation, alive.

“It’s more conceptual,” Waltz explains. “I didn’t die so the organisation didn’t die. I don’t know how many Bond movies there were in between where S.P.E.C.T.R.E didn’t feature, or where Blofeld did not appear in the flesh. And quite often, in a good story, you don’t know who the villain is for a long time. But, if it’s not right, then it’s time to do something else.”

Every time he takes on a role, Waltz tells me, he is determined not to fall into a cliché. In fact, avoiding clichés is so important to the actor that it took him six years to make the city he cracked back in 2009 his home.

“I was worried about that stereotypical idea of Los Angeles,” says Waltz, eyes darting outside the window to the bright sun and swaying palms. “But, I am happy to say, there was never any reason for me to be worried. My career there, my career here. The place may change, but I’m always me. The work is always mine. Of course it can be different over here, the roles may be larger, the fame bigger, but it’s still me.

“I was socialised, educated, and had my formative experiences in Europe. That’s a pretty solid core, so I’m not too worried that the American centrifugal forces will pull that out of whack. Also, this city is so dramatically different to the clichéd idea of Los Angeles we have in Europe. We think it’s still like the eighties, the nineties – kind of beachy, full of knuckle-heads and pot-smoking hippies. That’s rubbish.

“And that’s not the only thing we get wrong in Europe. We also like to think this romantic idea of Hollywood still exists.” Does it not? Waltz pauses, butters a small piece of bread, and tosses it into his mouth. He raises the napkin from his lap to cover his chewing mouth, and laments.

“It is a sad thing about the city of Los Angeles, in terms of the epicentre of film culture that it is considered as, that they no longer shoot films here. Go to the traditional movie studios, and they’re full – but of crappy, cheap TV shows.”

Lowering his napkin, Waltz waves his hand despairingly, as if in mourning for his new home. Money, he tells me, plays a crucial, defining role in cinema. But, when the investors and producers completely take over the process – people who not only have no clue about film, but also no interest, the process goes awry.

“It would be a much better bet for those money people to become day-traders, or Bitcoin-shufflers,” the actor hisses. “Movies have always been a financial endeavour, by the sheer fact that they’re so expensive, and investment is risky. But now, it’s become completely exchangeable: Is the investor for the movie, or the movie for the investor?”

"There’s no evolution happening in that unfortunate creature..."

According to Waltz, it would seem that the real villains sit not in spinning chairs, with white cats on their laps, but behind the desks of major studios. And the Hollywood fakery doesn’t end there. Mention method acting, and Waltz stops picking the cranberries from his salad and launches into another tirade.

“There’s no such thing as a method actor,’ he exclaims, arms wide. “If you have a method, that doesn’t make you a method actor. Today, ‘method’ is simply a way of dealing with an inferiority complex – something I’m sure I have, by the way – but we’re now trying to give this craft, a craft that basically hasn’t changed since the days of the Ancient Greeks, a new and exciting appeal.

“But rebels like [Elia] Kazan and [Lee] Strasberg invented method as a way to market yourself in the 40s and 50s – and that’s where so-called method actors today are stuck.” You get the feeling that Christoph Waltz is not an actor who likes to be stuck – nor is he one you’d want to corner.

Waltz has worked with many iconic directors. And, from Payne to Polanski, Tim Burton to Tarantino, the actor has a particular way to describe the techniques and talents of each. But, with his own directorial debut, real crime drama Georgetown, currently in post-production, how would Waltz describe his own capabilities behind the camera?

“It was probably one of the most problematic experiences of my entire career,” the actor sighs into his salad. “Because people, whose place it really isn’t, put themselves in a position to influence and shape a process that should happen completely differently. The wound is still open. And I’m not even near the end.

“Yes, it’s easy to overthink things, of course it is. But that also depends on your inclination and predisposition, in a way. So, yes I may overthink – but you can overthink overthinking as well. I mean, it’s fine. Overthink a little, but then get on with it.”

"If you have a method, that doesn’t make you a method actor..."

It’s easy to see when Waltz has confused himself – not that it happens often. Fluently trilingual – he dubs his own voice in many foreign versions of his films – Waltz is arguably one of the cleverest men in Hollywood. Still, his brow is furrowed, and he is clearly trying to figure out a better way to vocalise his point. Is intelligence a burden, I ask the actor?

“It never is. Or it always is. I don’t know,” he laughs. “I’m not saying you should switch your brain off. On the contrary, I wish I was surrounded by more switched-on brains. I have no time for switched-off brains. And that’s the worst thing – when the switched-off brains get in control.”

So we come to Trump. And, as soon as the larger-than-life President’s name has passed my lips, Waltz forces down his forkful of rocket and goat cheese to make way for a rising diatribe. But, before he swallows, I swoop in: how does Waltz think he’d fare as a politician?

“Terribly!” he barks, grin wide. “I don’t think I would have the hypocrisy that seems to be one of the basic requirements for that job. Well, maybe I would have it, but I wouldn’t want to nurture it within myself. And I don’t think I’d have the knowledge, either. You really have to know what you’re doing, otherwise you’ll end up like the clowns we already have.”

Before lunch, on a helipad in West Hollywood, we presented Waltz with a series of mirrors – all arranged under the masterful eye of photographer Gavin Bond. And, while the meeting played out considerably more amicably than Waltz’s last encounter with a Bond, it’s a concept that’s clearly been playing on the actor’s mind.

“The U.S have a President who is obsessed with his mirror image,” says Waltz. “Maybe not literally, but most certainly metaphorically. And he cannot properly handle it, because he thinks that that is what this world is about – his image of himself. He doesn’t have a clear view of anything, anything at all, because he doesn’t have a clear view of himself – or even an unobstructed view of himself.

“I would, however, grant him with…um. Um. Ah, I don’t grant him anything. Nothing. Forget it. He’s just never learned to deal with his own mirror image, with the image of himself. He’s completely underdeveloped as a human being. There’s no evolution happening in that unfortunate creature.”

Waltz, whose maternal grandfather was famed psychologist Rudolf von Urban, stretches back in his chair. “I personally think that mirror images, or the image of the self, can be a very destructive thing,” he theorises. “Especially in the business that we work in. Everyone loves talking about themselves, and anybody who says they don’t is lying. If we could, we’d just talk about ourselves all the time.”

It’s a bold and cerebral claim, especially from an actor whose two Oscar acceptance speeches simply listed people more important to his career’s success than himself. For, if there is one thing that would let Waltz down as a real-world villain – he’s got the curt manner, the craftiness, even the clipped European accent – it would be his humility.

“On account of the years I’ve spent working, I’ve just come to realise more thoroughly and more often what’s involved in making films work.” He pauses. “And it’s certainly not my talent.”

Even his Oscar statuettes are hidden away. “I don’t need to see them. I don’t have them out. But not because I’m so virtuous or modest or shy – I just don’t want, or need, to see them all the time.”

Awards-talk is not a favourite conversation topic of the actor. And, although it didn’t come easy, or fast, for Christoph Waltz, neither is fame. Does he attribute this disinterest to age? Or is there another dynamic at play?

“Perhaps age,” Waltz nods, pushing his cutlery together. “I’m sure I wouldn’t have dealt as well with the pressure earlier in life. I’m convinced I wouldn’t have. For the mere fact that it would have been the wrong thing at age 21. Because, at age 21, you’re meant to be thrown up and down and around and back and forth, because there is no other way to learn.

“It is pretty much the duty of a young man to abuse his career. I’ve dealt with that duty, of course, when I was 21 – but just not over here, or with so many eyes on me.”

Do you not enjoy stardom? “I’ve never thought about these things,” the actor shrugs, wryly. You must. “I don’t. I deal with them. Sometimes it’s enjoyable – other times it isn’t. Sometimes you meet wonderful people – other times it’s annoying. I meet certain individuals, and it’s lovely,” says Waltz, standing and tossing his napkin over the discarded cranberries.

And other times, I ask? Waltz leans in with a wolfish grin. “Torture.”

This interview is taken from the Nov/Dec 2017 issue of Gentleman’s Journal. For more cover stories from the archives, read why James Norton also wants to play a Bond villain…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.