Boris the bounder! Revisiting Johnson’s caddish days at Oxford

Everything we ever needed to know about the Prime Minister was revealed long ago. We investigate the politicians university career, looking for answers…

- Words: Simon Kuper

Like his role model Churchill, Boris Johnson spent years mastering the ancient craft of public speaking. Eton had offered unmatched opportunities to practise. Johnson ran the school’s Debating Society, and by the time he left was so well-versed in traditional speech-making that he could perform it as parody. His sister Rachel says:

“Eton Debating Society, PolSoc [Eton’s Political Society], all those places honed your oratorical abilities at a young age. They were given a huge head start, these guys. You’d get incredible heavy-hitters going to address PolSoc and talking to the boys. It’s like playing tennis – you can’t pick up a tennis racket and go and walk on Centre Court and expect to beat Roger Federer. So much of all these things are practice. You learn what lands, and you learn what doesn’t.

“And I think the problem is that women are frightened of trying and failing and being seen to try and fail”.

Johnson learned at school to defeat opponents whose arguments were better simply by ignoring their arguments. He discovered how to win elections and debates not by boring the audience with detail, but with carefully timed jokes, calculated lowerings of voice, and ad hominem jibes.

He went up to Oxford in 1983 as a vessel of focused ambition. Ironic about everything else, he was serious about himself. Within his peer group of public schoolboys, he felt like a poor man in a hurry. He started university with three aims, writes Sonia Purnell in Just Boris: to get a first-class degree, to find a wife (his own parents had met at Oxford), and to become Union president. At university he was always ‘thinking two decades ahead’, says his Oxford friend Lloyd Evans.

Whereas most students arrived in Oxford barely knowing the Union existed, Johnson possessed the savvy of his class: his father had come to Oxford in 1959 intending to become Union president. Stanley Johnson had failed, but his son was a star. Eton encourages boys to develop their individuality, or at least craft an individual brand, and nobody had done this more fully than Johnson.

Simon Veksner, who followed him from their house at Eton to the Union, recalls: “Boris’s charisma even then was off the charts, you couldn’t measure it: so funny, warm, charming, self-deprecating. You put on a funny act, based on the Beano and P. G. Wodehouse. It works, and then that is who you are”.

Johnson became the character he played. He turned self-parody into a form of self-promotion. Like many British displays of eccentricity, his shambolic hair and dress were class statements. Much like Sebastian Flyte’s teddy bear in Brideshead Revisited, they said: my privileged status is so secure that I am free to defy norms.

At Oxford, Johnson merged three archetypes from British popular culture: Brideshead, Wooster and the boarding-school bounder. The bounder is the rogue of his school, who doesn’t do his ‘prep’, smokes behind the rugger field, breaks bounds, romances girls and is always getting into ‘scrapes’. In adulthood, bounders traditionally end up hiding from their creditors in Australia.

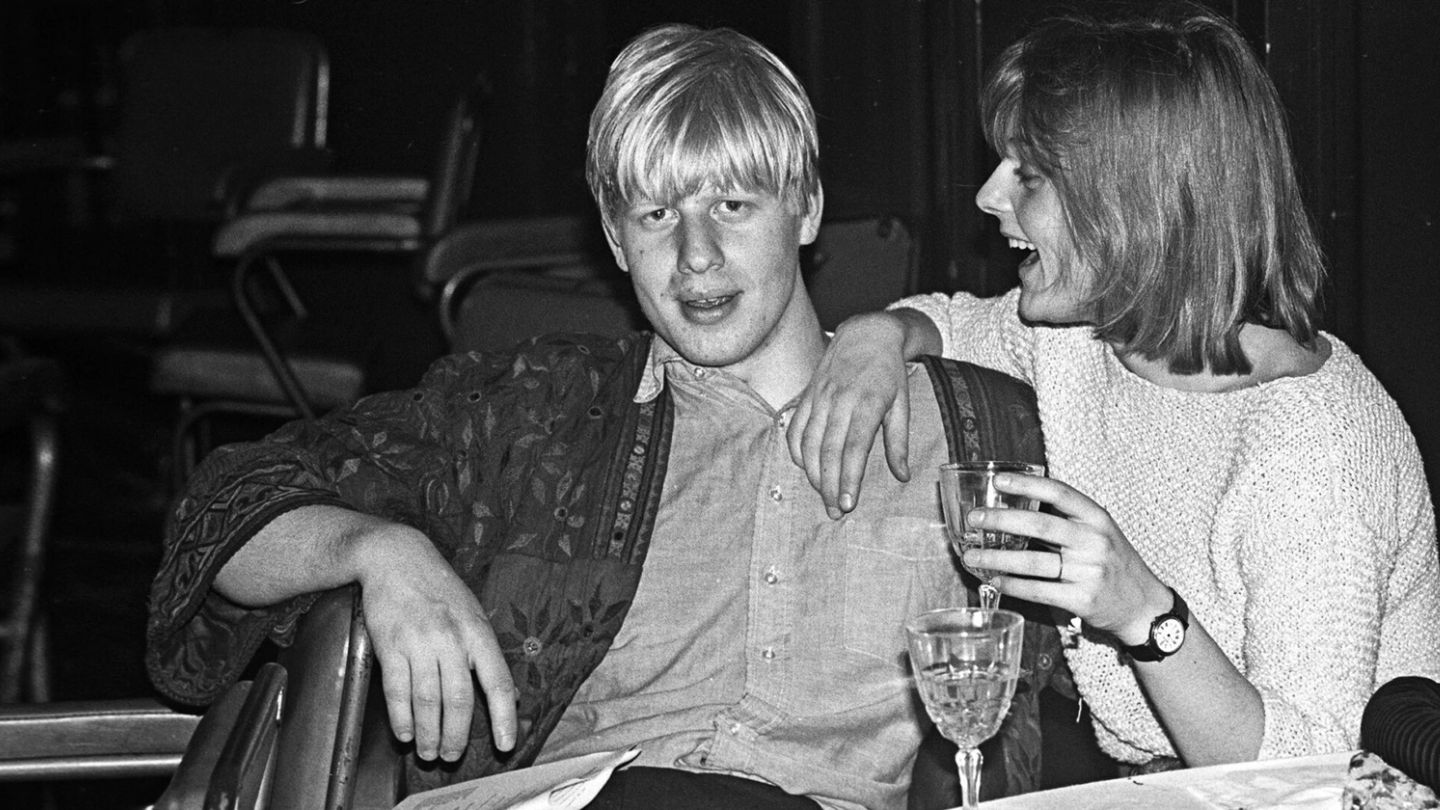

Johnson got off to the perfect start with his marriage ambitions: he acquired as his university girlfriend the posh and beautiful Allegra Mostyn-Owen, the Alpha female of their cohort. Cherwell, in an impressive scoop, managed to announce their engagement two and a half years before they actually married. Good-looking himself and regularly covered in student newspapers, Johnson became an ‘Oxford character’, one of the few undergraduates known beyond his immediate circle. Already, then, he possessed the political asset of being all too easy to write about.

Mostyn-Owen’s elite entrées supplemented Johnson’s own. She introduced him to the journalist Tina Brown, who was visiting Oxford to write about the death from a heroin overdose of the upper-class socialite Olivia Channon. Brown reports being traduced by Johnson, who supposedly ghosted an inaccurate attack on her in the Telegraph, under Mostyn-Owen’s byline. Brown claims to have recorded in her contemporaneous diary: “Boris Johnson is an epic shit. I hope he ends badly.”

“Boris Johnson is an epic shit. I hope he ends badly…”

Toby Young remembers the first time he saw Johnson speak at the Union, in October 1983:

“The motion was deadly serious – ‘This House Would Reintroduce Capital Punishment’ – yet almost everything that came out of his mouth provoked gales of laughter. This was no ordinary undergraduate proposing a motion, but a Music Hall veteran performing a well-rehearsed comic routine. His lack of preparedness seemed less like evidence of his own shortcomings as a debater and more a way of sending up all the other speakers, as well as the pomposity of the proceedings”.

To Young, another who had come up to Oxford with his head full of Brideshead Revisited (the TV version), Johnson represented “the ‘real’ Oxford, the Platonic ideal”. He admits, “I was completely swept up by the Boris cult”. Johnson, he said, “was the Biggest Man on Campus. He was the silverback gorilla, the alpha male”.

One young debating hopeful of the day was Frank Luntz, the future American pollster who has become known as a master of political language. A self-proclaimed ‘word guy’, Luntz invented the phrase ‘climate change’ for the George W. Bush administration so as to make ‘global warming’ seem innocuous (something he now says he regrets). He recalls:

“Boris was brilliant. He bumbles through the details but God does he know the substance. I had never met anyone like him, and I still haven’t. Boris gave a speech on the Middle east – it’s the best Middle east speech to this day I’ve ever heard, because he talked about it in terms of a playground, and kids attacking the little kid on the playground. Boris created a brilliant metaphor and then made the argument around that”.

Johnson also benefited from the quality of debating competition, says Luntz: “I’ve never seen a class of more talented people than that class of 1984–86 at the Oxford Union. I was twenty-two when I got there and I looked up to people who were eighteen or nineteen years old, because of their talent”. Luntz singles out Nick Robinson, Simon Stevens and Michael Gove. He told me:

“Any one of those three, when they rose [in a debate] to intervene, the entire chamber shut up, there wasn’t a sound, because everyone knew that when they were recognised, the [previous speaker] was dead, because they were so incisive. Just bring in the ambulance and take out the body, because the three of them could cut you up and show you your heart before you collapsed. We can’t do that in America, nobody can.

“If you made a good argument but you didn’t have the backing for it, you were so embarrassed that you couldn’t show yourself at the bar after the debate. If you didn’t have the facts, if you didn’t know the counterarguments, they would figure it out and destroy you. You had to know everything because you had no idea what was going to come at you – and it came at you during your speech.

“It’s the most wonderful [speaking] style ever. It’s like a mental massage. Oxford was the perfect training ground. It trained them because they were surrounded by people who were just as talented as they were, just as career-driven as they were, they were surrounded by thousands of them“.

Anthony Gardner, another American contemporary of Johnson’s, later US ambassador to the EU, was less impressed:

“Boris was an accomplished performer in the Oxford Union where a premium was placed on rapier wit rather than any fidelity to the facts. It was a perfect training ground for those planning to be professional amateurs. I recall how many poor American students were skewered during debates when they rather ploddingly read out statistics; albeit accurate and often relevant in their argumentation, they would be jeered by the crowds with cries of ‘boring’ or ‘facts’!”

Politically, Johnson shared with most Oxford Tories of his generation a generalised faith in Thatcherism. The prime minister in her 1982–87 heyday, their formative political years, was a role model. She instinctively chose the uncompromising solution. She steamrollered all opponents, from Tory ‘Wets’ to Argentinian conscripts. She stood for unabashed material advancement for the winners, and a world in which Britain could still make the rules through willpower alone.

After her death in 2013, Johnson would call on Oxford to endow a new Thatcher College. “Why not have a college in honour of their greatest post-war benefactress as they rake in the doubloons from international student fees?” he asked.

The undergraduate Johnson quickly became king of all he surveyed. In 1984, a sixth-former named Damian Furniss came to Johnson’s college Balliol for his entrance interview. “I was a rural working-class kid with a stammer from a state school which hadn’t prepared me for the experience,” Furniss would recall in 2019.

“My session with the dons was scheduled for first thing after breakfast, meaning I was staying the night and had an evening to kill in the college bar. Johnson was propping up with his coterie of acolytes whose only apparent role in life was to laugh at his jokes. Three years older than me… you’d have expected him to play the ambassador role, welcoming an aspiring member of his college…

“Instead, his piss-taking was brutal. In the course of the pint I felt obliged to finish he mocked my speech impediment, my accent, my school, my dress sense, my haircut, my background, my father’s work as farm worker and garage proprietor, and my prospects in the scholarship interview I was there for. His only motivation was to amuse his posh boy mates”.

At around the time of this encounter, Johnson was running for Union president against the grammar-school boy Neil Sherlock. The election dramatised Oxford’s class struggle: toff versus ‘stain’. Sherlock, later a partner at KPMG and PwC, and briefly a special adviser to the Liberal deputy prime minister Nick Clegg, was the first in his family to attend university. He says that when he arrived at Oxford, “I’d never seen a debate in my life. I’d never seen anyone in black tie, let alone in white tie”.

He recalls: “Boris Mark I was a very conventional Tory, clearly on the right, and had what I would term an Old Etonian entitlement view: ‘I should get the top job because I’m standing for the top job’. He didn’t have a good sense of what he was going to do with it”.

Allegra invited Sherlock to tea and asked him not to stand against ‘my Boris’. Undeterred, Sherlock campaigned on a platform of “meritocrat versus toff, competence versus incompetence”. Johnson mobilised his public-school networks (he seemed short of close friends) but even the 150 or so Etonians up at Oxford at the time proved too small a political base in the new mass Union.

Johnson’s candidacy also suffered from his Toryism. Conservatives may have been the largest faction within the Union, but they were a minority in the university as a whole. Most Oxford dons of the time were anti-Thatcher, too. Denying her an honorary degree in 1985 to protest her cuts to education and research was the university’s seminal political statement of the decade. “Why should we feed the hand that bites us?” asked one don. Luntz recalls that Oxford considered Thatcher “the most evil living person on the face of the earth”. He himself felt he was socially excluded for speaking for her.

In the Union election, Sherlock beat Johnson, and came away underwhelmed by his opponent: “The rhetoric, the personality, the wit were rather randomly deployed, beyond getting a laugh”. Sherlock expected OUCA’s president Nick Robinson to become the political star, and Johnson to become a ‘rather good journalist’. Instead, Robinson went on to present the Today programme (where in October 2021 he told a verbose Johnson, “Prime minister, stop talking”).

The emotional intensity of a Union election is extraordinary: betrayals abound, participants are at their most sensitive phase of adult life, and nobody is getting much sleep. The candidates are running for the most prestigious post any of them will have ever held at that point in their lives – and quite likely the most prestigious the winner will ever hold. Losers often burst into tears. They feel that their very essence has been rejected, not just whatever political views they might (or might not) hold. Johnson’s defeat to Sherlock wounded him, and he learned from it. “It was, quite likely, the making of him as a politician,” writes Purnell. “It taught him the unassailable truth that no one can truly succeed in politics if he relies entirely on his own cadre”.

But Etonians tend to get second chances, and a year after his humiliation, he ran for president again. He had absorbed another truth: that personality could trump politics. The second time around, he disguised his Toryism by presenting himself as an unthreatening funny man – “centrist, social democrat, warm and cuddly”, sums up Sherlock.

He even managed to forge an alliance with a Union hack from Ruskin College, and rallied its student body of mostly adult working-class trade unionists behind his slate. Cherwell’s diarist John Evelyn mock-praised ‘Balliol’s blond bombshell’ as “the unstoppable force for Socialist in the Palace of the People debating society (the Union to you) … Who can stop our Old Etonian Leninist from stamping his personal hammer and sickle all over the Union?” Thrown in among leftists and liberals, Johnson learned to flourish by spoofing himself. “He got away with being a Tory by being funny,” says his sister Rachel.

And why not? Since the Union president couldn’t make policy even about students’ lives, and Johnson wasn’t very interested in policy anyway, it was all just a power game. Johnson’s second presidential campaign was more competent. Luntz – earning his first-ever consulting fee, of £18,019 – conducted a poll for Johnson in which, as Luntz recalls, almost all the questions were about students’ sexual habits. He says now: “My mother was so embarrassed because it made The New York Times. She said, ‘How dare you ask people those questions?'”

But in fact, the sex was just a cover, says Luntz: “I knew it would be so controversial that no one would think, ‘Actually this was a poll done for a political campaign'”. He slipped in two questions about the Union that were intended to identify which candidate Johnson should strike a deal with about trading second-preference votes.

In this second campaign, Johnson also worked his charm beyond his base. Gove, a fresher in 1985, told Johnson’s biographer, Andrew Gimson: “The first time I saw him was in the Union bar … He seemed like a kindly, Oxford character, but he was really there like a great basking shark waiting for freshers to swim towards him”. Gove, who campaigned for him, admits: “I was Boris’s stooge”. And then, using the same phrase as Toby Young: “I became a votary of the Boris cult”.

Johnson’s persona was the perfect vehicle for a slate. In the English context, it seemed right and just that the highest political office should go to the most charismatic Etonian of his day. With the votaries assuming their natural places around him, he won the presidency. Johnson’s defeated opponent Mark Carnegie later reflected: “Sure he’s engaging, but this guy is an absolute fucking killer”.

That was what it took. As Toby Young wrote in the Union’s house magazine in 1985: “It doesn’t matter how unpopular you are with the establishment, how stupid you are, how small your College is or how pretentious your old school: if only you’ve got the sheer will you can succeed”. The types who succeeded in the Union, Young explained, were people who “when confronted with any social environment… perceive only the hierarchical conditions which determine people’s status within it; and they have no means of relating to other individuals other than as tools and enemies”.

Young wrote that it was lucky that that Union existed – “that in an environment as full of ruthless, sociopathic people as Oxford, there should be an institution that sucks them all in, contains all their wilful energy and grants them power only over each other”. He concluded his article: “Let us hope with all our hearts that today’s Union Presidents will become tomorrow’s MPs, Cabinet members and Prime Ministers for then, like today, we will at least know where they are”.

“Sure he’s engaging, but this guy is an absolute fucking killer…”

Johnson’s gift turned out to be for winning office, not doing anything with it. He didn’t make much of his presidency, recalls Tim Hames, a Union politician of the time: “The thing was a shambles. He couldn’t organise a term card to save his life. He didn’t have the sort of support mechanism that he realised in later life that he required”.

Once elected, Johnson also dropped his centrist disguise. When Balliol’s Master Anthony Kenny was contacted by a Social Democratic Party MP who needed an intern, Kenny replied: “I’ve just the man for you. Bright and witty and with suitable political views. He’s just finished being president of the Union, and his name is Boris Johnson”. But when Kenny told Johnson about the job, he laughed: “Master, don’t you know I am a dyed-in-the-wool Tory?”

After graduation, Johnson wrote a telling essay on Oxford politics for his sister’s The Oxford Myth. He starts, characteristically, by stating the case against the Union:

“Nothing but a massage-parlour for the egos of the assorted twits, twerps, toffs and misfits that inhabit it… To many undergraduates, the Union niffs of the purest, most naked politics, stripped of all issues except personality and ambition… Ordinary punters are frequently discouraged from voting by this thought: are they doing anything else but fattening the CVs of those who get elected?”

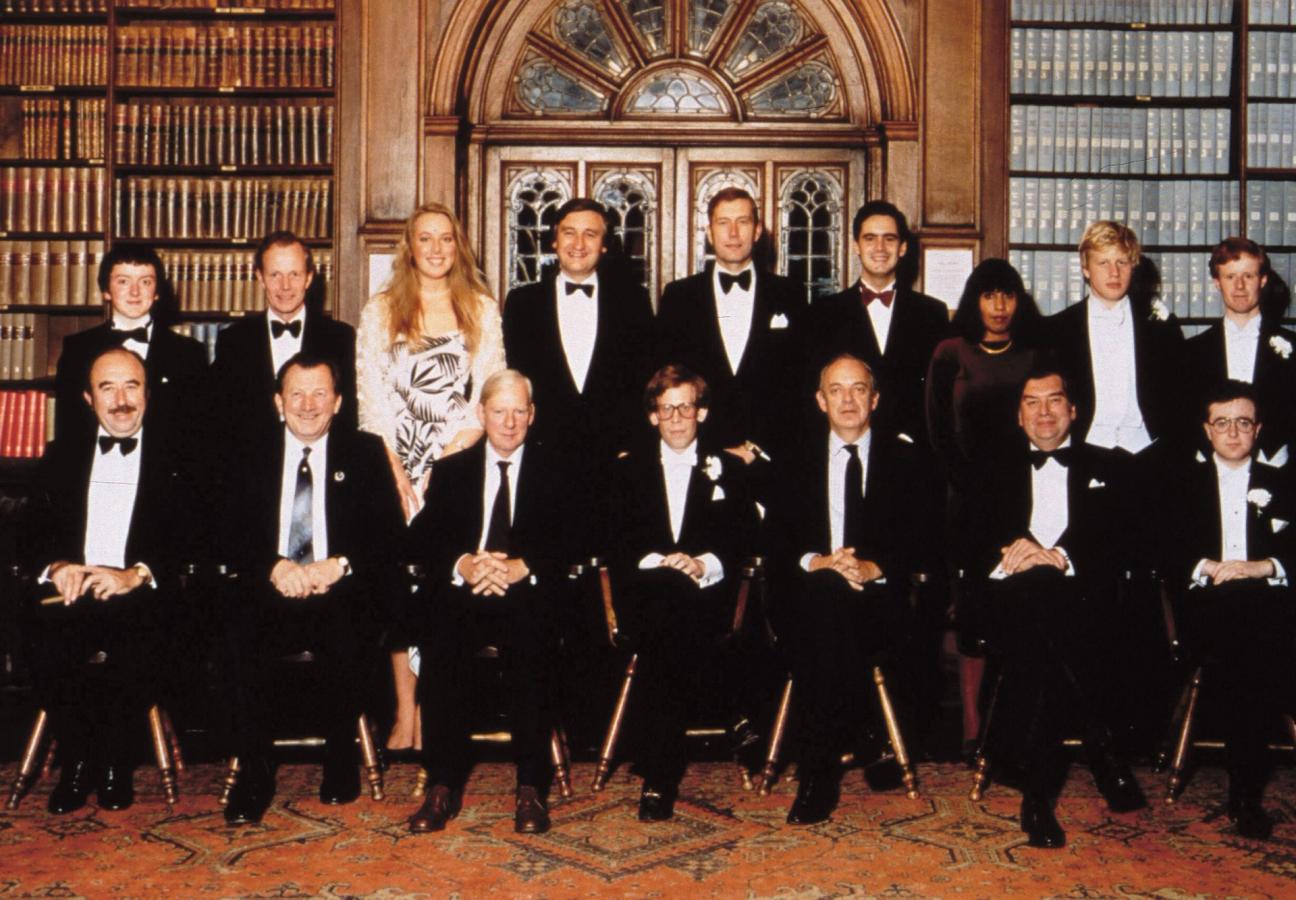

Still, he noted, the glittering prizes of London were within easy reach: “The best way to get an idea of the importance of the Oxford Union in British political life is to spend a quarter of an hour looking at the standing committee photographs as they wend back up the stairs and the landing to the beginning of the century”.

He critiques the undergraduate appearances of various future stars (“Benazir Bhutto wears very odd dresses… Heath looks fat”) before ending with the chosen role model: “As we near the top of the stairs, we see a very youthful figure sitting cross-legged at the front of the group, like the scorer in the school cricket team. He looks about thirteen. He is Harold Macmillan”.

His essay then tackles the great question: how to set about becoming the next Macmillan? Well, even if you speak like Cicero, you will never get electoral success “without first grasping and mastering the principles of hacking”. Johnson advises student politicians to assemble “a disciplined and deluded collection of stooges” to get out the vote. “Lonely girls from the women’s colleges, very often scientists” were particularly useful:

“With their fresh complexions and flowery flocks, they are the prototypes of local Conservative Party workers. Brisk, stern, running to fat, but backing their largely male candidates with a porky decisiveness… For these young women in their structured world of molecules and quarks, machine politics offers human friction and warmth”.

Johnson in this passage is reflecting on the first society he had encountered in which women played some role in power structures. Reading it, you realise why almost all Union presidents who become Tory politicians are men (and arts graduates).

Johnson added: “The tragedy of the stooge is that… he wants so much to believe that his relationship with the candidate is special that he shuts out the truth. The terrible art of the candidate is to coddle the self-deception of the stooge”.

This article was taken from the Summer 2022 issue of Gentleman’s Journal. Take a look inside the latest magazine here…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.