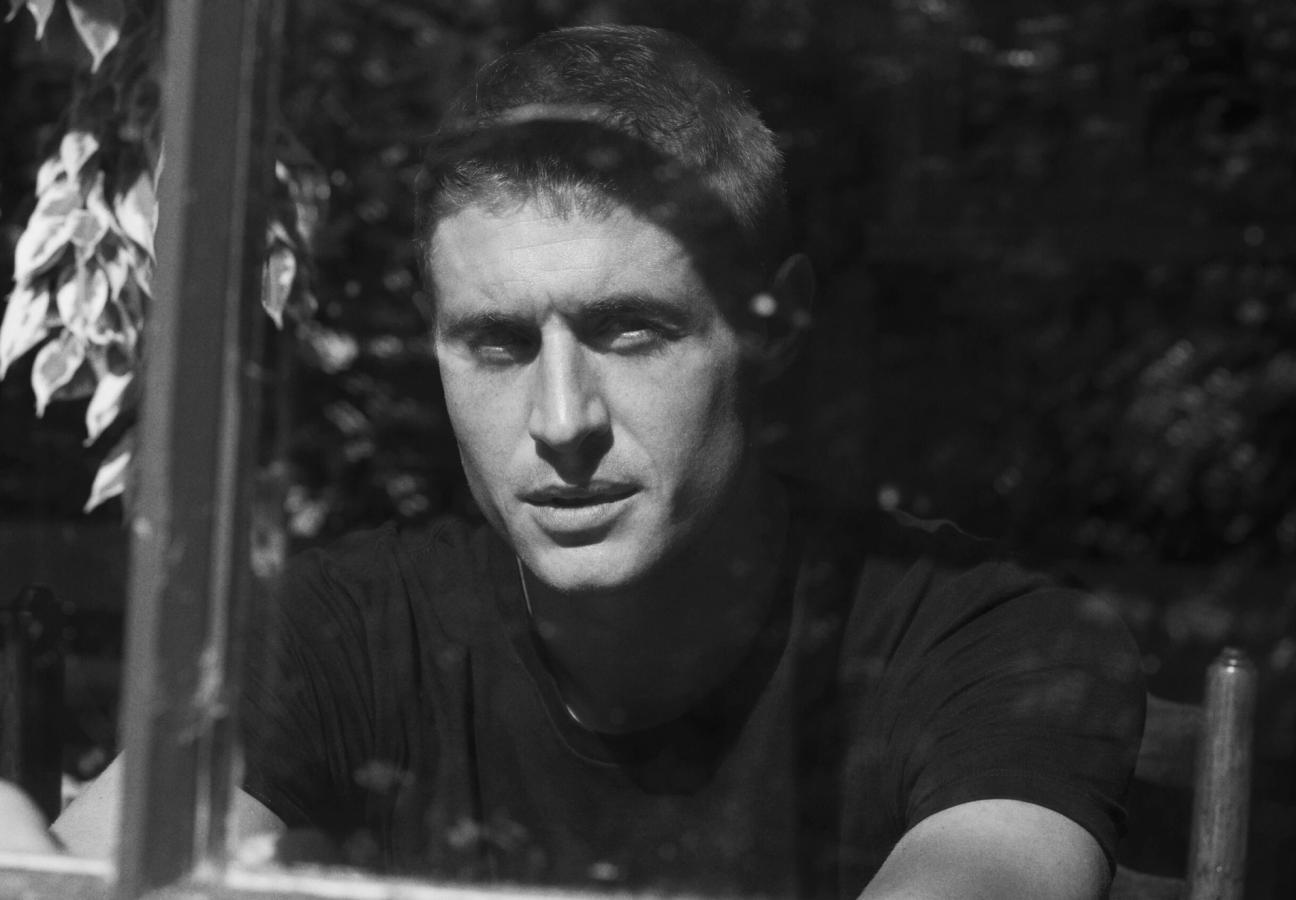

Words: Joseph Bullmore

Photography: Joseph Sinclair

We’re on a Zoom call (isn’t everybody), and Max Irons has just asked me whether I mind if he smokes a cigarette. In an entirely different room. In his own house. Many, many miles away. “Well, I don’t know what the etiquette is these days,” he says sweetly, and for a moment I think he’s about to offer me one through the monitor (I would have accepted, of course).

You can tell a lot about a man from his Zoom form. Some are brusque and clinical. Some are poorly framed and echoey. Others have cynically curated their backgrounds to give off just the right impression — a little Dostoyevsky here; a Chagall exhibition poster there. (And I say this as a man who bought four expensive house plants for a FaceTime with his estate agent). But the best make you feel that there’s no screen involved at all.

Perhaps that’s the definition of a good actor, actually. It’s certainly one you could apply to Max’s performance in Condor, his recently-returned espionage thriller. The whole thing’s too real, if anything. Crooked governments. Global plagues. Official incompetence. Activist hackers and conspiracy theories. Redacted reports and foreign interference. And in the centre of it all — caught in the whirlwind of some accidental, parallel 2020 — is Joseph Turner, an idealistic young CIA analyst who’s slowly realising that the true levers of powers are being pulled off stage. Well, you and me both, Joe. (You can watch the second series on Sky One right now, if you like, though you might think you’ve stumbled upon a documentary.) It is utterly gripping and very good fun and quietly terrifying.

Max and I spoke about politics and nuance and the current cultural climate, of course. But we spoke about other things, too. About how his father — a chap called Jeremy Irons, I’m told — cried in the interval of Max’s first ever performance; about how cycling is a handy window into a man’s soul; about the best flavour of Calippo; and about the relative merits of David Beckham as James Bond. No barriers, no screens. Feel free to smoke throughout.

How are you Max? You’ve got a lovely bookshelf behind you. Everyone’s been judging everyone’s bookshelves on Zoom lately, haven’t they…

Well, I’m not much of a reader. And most of them are from when I was about 12 — there’s the odd colouring book in there…

I was thinking that maybe this odd world of Zoom calls isn’t actually that unusual for an actor, because you spend your whole life looking down a camera lens, pretending it’s a person…

I’m not going to lie. I’ve been fortunate enough to rather enjoy this lockdown in a few different ways. As an actor, you’re always thinking, even if you’re employed, that unemployment is just around the corner. But during the lockdown, everything stopped. And so you got to have a bit of time without all that mental noise.

But Zooms are weird. Last night, in fact, I was supposed to start at the Donmar [Warehouse] in a play, and obviously it was cancelled. And so we were doing these sort of rehearsed readings for the donors over Zoom. And it was really good. I was dreading it. I thought it was going to be an unpleasant experience because of the limitations of this technology. But it really wasn’t. We had 70 families — kids, old people, young people. And we got all these comments coming up the side — people writing things like: “thank you so much for the very special privilege of getting to see something magical in the making”. It was really touching.

Has this period given you any time for any new endeavours?

I’m very into cycling. I just love bikes. And of course the city has been empty, which has been pretty great. Obviously you see the empty streets, but you see things beginning to open back up, you see food banks, you see the state of play with homeless people in the city. It’s a nice way to sense how things are.

So you’re not writing a novel then?

Oh. I mean, obviously I’m writing a few novels. A few plays, a few film scripts, all that sort of thing. No, I’m not, Jesus Christ!

I’m sure there’s some pop psychology we could apply to cyclists, about how you like to struggle up hills, but then enjoy the downhills of life, too. I don’t know. There must be something there…

Oh, definitely. I remember I went to Spain to ride my bike, and I was going up this mountain, and it was quite painful. So there was a bit of self-flagellation involved. And I ended up thinking about this teacher. He just popped into my head. He had told me I’d never be any good at rugby because I was too skinny. And I literally hadn’t thought about that since it happened, many, many years ago — and I started crying. I was just thinking of little me, and then about how I’m on this mountain, and how it hurts, and how I’m going to get to the top no matter what he said.

What were you like at school?

I was very dyslexic at that point. I still am very dyslexic. So most of my time at school was just struggling.

And you weren’t sporty…

I spent a huge amount of time by myself in those days. I was always climbing up trees. I wasn’t very popular at all. I don’t know — I was a bit of a loner.

Were you a good actor?

No, no way! I wasn’t an actor. Acting for a dyslexic kid is difficult because you’re told: “get up on stage and read this and do it in a confident way.” My dad came and saw me in something, and in the interval he went outside to the hockey pitch, to the AstroTurf, and he cried, apparently. Because I looked so scared up there. It was Oliver, the musical. I was basically an extra but I had one line.

Even to this day, if I have an audition, occasionally they’ll throw something at you and say: “Can you just give this scene a read?” And you have to be honest and just go: “Listen, I’m a little dyslexic. Give me 20 minutes, I’ll come back, and I’ll do it for you.” So it’s fine. So many actors are dyslexic. So many.

There must be something in that as well…

I think there is. I remember getting into Guildhall. We had to fill in this form to say if we had any sort of disabilities. And I wasn’t sure. So I called up the school and I said: “Does dyslexia count as a disability?” And they said: “No, it’s practically a qualification.” It was quite nice to hear.

That’s a good way to put it. So let’s go back to that moment on the AstroTurf, when your father was crying. Do you think, in a way, he’d always hoped that you would be dramatic like him?

No, I don’t think it was that. And I don’t think he wanted that for me. I think it was that he saw his son struggling, and perhaps felt that I hadn’t been offered enough nurturing or something.

But he didn’t want me to be an actor at all. Neither did mum. I think they both understand how difficult it is on so many levels to be an actor, how it’s not necessarily a path to happiness or success or security or good relationships. There are a lot of traps and things. I think they were nervous about it. But I think once they figured out that I was serious about it and hopefully going about it in the right way, they would support me.

Did having successful acting parents make you better prepared for those difficult bits of the industry — for the trappings of fame and disappointment and rejection? Do you think that it made you more grounded?

Do you know, I actually think it did. I also think it probably cost me. Because there are a lot of things that I just don’t do that I probably should do. Social media, for instance, and going to parties, you know — chasing fame a little bit. It sounds bad to say that, but that’s part of our value. But my parents never really did that. And because I sort of grew up with it, I had a sense of what it really translates to. It doesn’t mean health. It doesn’t mean happiness. So I didn’t go after any of those things. Probably to the detriment of my career.

There must be some intoxication to fame. There must be some moments, especially when you’re young, when it must feel nice to be recognised. Is that true?

I’ll be honest with you, I never felt that way. The first major role I got was in a film called Red Riding Hood, which was made by Leonardo DiCaprio’s production company. And we had the same director as Twilight. Basically, It was a bit of a knockoff. And, you know, I was part of a love triangle: two angsty guys, fighting for the girl. And it had the sort of dialogue that you’d imagine.

When it came out, it was panned across the board. But then you’ve got to sell this thing. You’ve got to sell it for months and months and months, and you’ve got to go to a premiere and things like that. And inside you’re thinking: “Well, I don’t actually like the thing that I did. I’m not proud of it.” And that, to me, outweighs any fame.

Did you feel that you gave a bad performance, or did you just feel that the script was bad?

I was happy with my work. But I remember Gary Oldman was in Red Riding Hood. In one scene, in a big church square, in a big studio, he had to ride in on this horse. He was clad in this grand armour. And the minute he got his horse to stop, it took a huge shit. And Gary jumped off and said: “We’ve got our first critic!” That sort of sums it all up.

My dad once said in an interview — and I told him off for it, for talking about my career — he said: “You know, in the old days we got to fail privately: to do repertory theatre for years, and you could f**k up quietly on some little stage somewhere.” Now it’s very different.

Would you ever go to your parents for feedback on a role? And if you did, would they be honest with you?

They couldn’t be if they tried. “All my ducks are swans.” I think that very much applies. And you’re very perceptive with your family. Too perceptive. If I asked my mother, “How do you think I was?” and saw a flicker of an eyelash, I’d think: “F**k, she hated it, that’s it.”

Let’s talk about Condor. It feels like you can’t talk about this show without talking about politics, because it seems so eerily pegged to the current moment. There are global plagues. There are corrupt and incompetent governments. There are activists, hackers, and conspiracy theories all over the shop. It is the most 2020 show ever, in a way…

What I quite liked about the character I played was that when you first meet him, he’s a bit of an idealist, perhaps a bit naive. And he’s got that instinct that you see a lot of people having these days, which is that this institution or that branch of government is destructive. Let’s burn it down to the ground. And then he learns that, in fact, that’s not the way the world works. And if you ever hope to make a change, you have to recognise the faults in a system, and work from within it to try and change it.

You’ve got to ask yourself, how am I complicit in this state of affairs? It’s all well and good looking at South America or looking at the Middle East and going: all these wars are illegal. They are, no doubt about it. But you also need to say to yourself: well, I’m enjoying quite a few privileges off the back of these things. I have cheap and accessible oil. I’ve got year round avocados that are cheap as mud. I’ve got a cell phone that can do all sorts of things, and every time I get a new update, I click “agree” to all these terms and conditions that are shaving away at our rights and protections. So I think we have to begin to ask ourselves: are we happy with that exchange of goods? Are we in cahoots with the various systems that we claim to want demolished? And that’s what I quite like about Condor. That they take quite an unbiased look at these things, and they pose more questions than anything else.

When you were exploring the role, researching the character of Joe, did you get deep into the conspiracy theories, into WikiLeaks, into the backwaters of the internet?

I’ve got a notebook application on my computer and it’s full of research about Edward Snowden, because he was a data analyst too. I looked into a lot of the things that he revealed about some of the NSA’s monitoring operations and about how far reaching and effective and permanent they are.

Are there any conspiracy theories you can get behind?

I think Russia’s involvement in our democratic process — someone called that a conspiracy theory. I don’t think it’s a conspiracy theory at all. Apart from that, I can’t think of any. I mean, we landed on the moon. And I found out the other day that, in response to the ‘flat earth’ conspiracy, there’s quite a large movement claiming that we are, in fact, on the back of a dinosaur. I like that! I think it’s got some merit…

I saw you once say you’d really like to play a politician. If you had to play one of the political players of the moment, who would it be?

I mean, I’m quite enamoured with Keir Starmer. Or maybe I could do Dominic Raab, except he would probably make for quite a boring movie. He’s quite tall, so I could do him.

The question that gets asked any time an English bloke plays a spy, is: “Do you want to be the next James Bond?” Well, do you?

I don’t see myself as Bond as it’s never something I’ve yearned for. I always raise my eyebrows slightly when I see that question. The Daily Mail does it all the time. Then the young actor gets interviewed and they get asked: “What do you say to the rumours?” And I always love the responses. They’re like: “Oh, I haven’t heard anything,” but they phrase it in such a way as to say: “But I’m definitely available!”

Personally, I’d be too scared to take Bond on. It would dominate your career and your legacy. And also the stakes are so high and people really care about that property. If you fuck that up — Jesus.

Do you know what your odds are? I was on OddsChecker.com this morning…

Go on.

You’re on at odds of 200/1 to be the next James Bond. And I can tell you that you’re just behind John Hamm, at 150/1. And that you’ve edged out Chris Eubank, the boxer, at 250/1. So you’re in great company. For a bit of context, David Beckham is at 500/1.

Well, at least I’m above him!

You mentioned before how you’re not on social media…

I used to be on Facebook and I didn’t come off out of any principle. I just came off it cause it made me f**king miserable. I don’t have the personality for it. It all felt insincere and mentally unhealthy. And since then it’s got worse with the way Instagram and Twitter work and the inherent limitations to them. No, it ain’t for me. And also I don’t trust myself. These days, if you say a thing and you get it wrong, that can be it.

In the olden days, you sort of had your five channels on TV and you had your street. You had your neighbours and maybe they had a new VW Golf. Maybe they had a new cafetiere that was quite fancy, or a fancy doorbell. And that was the extent of the jealousy. But now you look at some people’s feeds and it’s: “Oh, here I am boarding a private jet. Or here I am with my new Audi that I got given for free or something.” And you think that’s normal, and that what you have is lesser. It definitely exploits psychological kinks that we all have.

And finally: what’s your favourite ice cream?

Oh, I’m a big ice cream man. I’m an orange Calippo guy. But if you can get hold of them, and they’re quite rare — a pure strawberry one is good, too. And Coca-Cola, they’re quite good — they have little bits in them that pop on your tongue. Brilliant.

Season two of Condor is on Sky One now

And talking of bikes — why not read up on the best bikes for commuters?

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.