Words: Alec March

For more than a century, the Vanderbilts were the epitome of the American Dream. But after a series of bitter divorces, poor financial decisions and high-profile fallouts, the world’s richest family came off the rails.

The policemen held back the crowds massed outside the Vanderbilts’ newly-built residence, Petit Chateau on Fifth Avenue, as carriages deposited 1200 guests for a party that The New York World newspaper declared was ‘An Event Never Equalled in the Social Annals of the Metropolis’.

It was 26 March 1883 and the cream of Manhattan high society was arriving for the most lavish costumed ball in American history. For onlookers this was the ultimate red carpet event.

In 1865, Cornelius Vanderbilt was the world’s richest man, with a net worth of $75 billion in today’s money

Whether it reached the debauched excesses of Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 adaption of F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is doubtful, but we do know that the hostess, Alva Vanderbilt, wore the pearls of the 18th-century Russian Empress Catherine the Great.

Already the richest family in the world, this was ostensibly a house-warming party. In fact it was Alva’s big attempt to break her family into New York’s high society, then dominated by blue bloods such as the Astors. ‘Alva wasn’t interested in another house,’ remarked Arthur T Vanderbilt II in Fortune’s Children, a history of the family published in 1989. ‘She wanted a weapon.’

And 12 years later she weaponised her beautiful, 18-year-old daughter, Consuelo, forcing her to marry the 9th Duke of Marlborough, first cousin of Winston Churchill. The duke got $2.5 million (now worth more than $70 million and used to renovate and landscape the grounds of family residence Blenheim Palace) and the Vanderbilts got a confirmed duchess on the books. Soon Consuelo was moving in the same circles as Edward VII, Kaiser Willhem II and the Tsar of Russia.

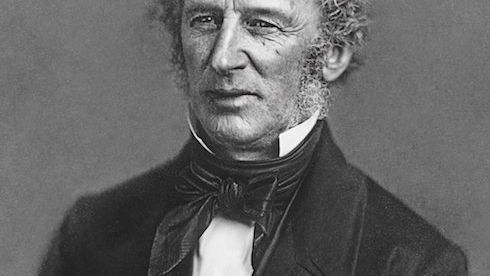

The Vanderbilts had come a very long way since Consuelo’s great-grandfather Cornelius Vanderbilt, who started out, ferrying people from Staten Island to Manhattan in the early 1800s. In so doing they didn’t just amass one of the greatest fortunes the world has ever seen, they represented the ideals of the American dream and epitomised the glamour and excess of the Gilded Age.

Born in 1794 to a Dutch immigrant family, Cornelius Vanderbilt left school at 11 to work on his father’s ferry in New York Harbour. It was not an auspicious beginning. But as his biographer TJ Stiles points out, young Cornelius was the ‘right man at the right time in the right place’. Over the next 70 years, the Commodore – a nickname he was given as a young man from other boatmen –created America’s first great mega-corporation, one that would help shape and be shaped by the economic development of the US.

But first, a stroke of luck: in 1817, the Commodore met ferry business owner Thomas Gibbons, who asked him to captain his steamboat between New York and New Jersey. This got Vanderbilt into steamboats – the new technology of the day. It also broadened his economic horizons, gave him social contacts and by 1830 Vanderbilt was running his own steamboats from New York to the surrounding areas. He had made it.

‘Vanderbilt was extraordinary,’ says Stiles, who won the Pulitzer for his 2009 biography, The First Tycoon: The Epic Life Of Cornelius Vanderbilt. ‘He was poorly educated, intensely competitive, and determined to learn any skill or knowledge required for success.’

Vanderbilt’s next big break came in 1849, with the Californian Gold Rush: he got involved in moving people from the East to the West and had a bold idea. ‘He launched an attempt to build a canal across Nicaragua,’ adds Stiles. ‘The canal, of course, was never built, but he started to combine steamships and transit operations across Nicaragua. It created a truly national and international figure.’

Alva at her 1883 party

Then came the greatest moment in Vanderbilt’s astonishing career: in the early 1860s, at 67 years of age, he sold his steamboats and bought his way into a string of railway lines, including the New York Central Railroad. By 1870 he was the king of the railways and was building a new station in Manhattan – Grand Central was born. His statue stands outside it today.

Stiles says he achieved all of this with an astonishing attention to detail, a strategic grasp and commercial ruthlessness. ‘Vanderbilt said, “If I couldn’t run a steamship alongside my competitor for 20 per cent less, I would just quit it,”’ adds Stiles, who compares him to modern figures such as Sir Richard Branson, Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos of Amazon. On his death in 1877, the Commodore left, a fortune worth $100 million, which was more than the US government had in the bank and the equivalent to $1 in every $20 in circulation. His wish was for the Vanderbilts to forge a dynasty.

‘Keep the money together,’ he declared.

If only people did what they were told. Today, if you look for the Petit Chateau on Fifth Avenue you’ll find an outlet of Zara because it was demolished in 1926. Demolition was a fate that befell at least six other Vanderbilt mansions built on Fifth Avenue between 1880 and 1905. The exception is one of the so-called Marble Twins built by George Washington Vanderbilt, now home to Versace’s flagship store. Another of George W Vanderbilt’s houses survives – the 250-room Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, built in the 1890s. Believed to have absorbed $4.4 million of George’s $5 million inheritance, the property is the largest private house ever built in the USA.

Consuelo with Winston Churchill

Size is not everything, of course. For sheer, improbable ostentation, look no further than the Marble House in Newport, Rhode Island. Completed in 1892, it was built for Alva Vanderbilt as a 35th birthday present from her husband, William. It cost $11 million (several hundred million in today’s money) and resembles the White House, except it’s far grander. With 14,000 cubic metres of marble its highlights include a grand staircase in yellow Siena marble, modelled on that of Petit Trianon (Marie Antoinette’s private sanctuary), the Gold Ballroom and a dining room with a Pink Numidian marble fireplace inspired the one in Salon d’Hercule at Versailles. Not to be outdone, Cornelius Vanderbilt II’s nearby summer pad, an Italianate palazzo named The Breakers, was completed in 1895, boasting 70 rooms and a footprint of an acre. Today, like the Marble House, it’s a museum.

But even as they were spending it, the Vanderbilts were still raking it in. William Henry Vanderbilt, the Commodore’s successor (who estimated he earned $19.73 a minute) left a fortune worth $200 million – around $50 billion in today’s terms – when he died in 1885. And despite the spending, the next head of the family, Cornelius Vanderbilt II, continued to make the family’s empire thrive, dutifully running the business with his brother, William.

After this point, Cornelius II’s descendants proved to be better spenders than earners – and they also died young. Cornelius II’s son and heir Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, a noted coach-racer, narrowly missed boarding the Titanic, but went down three years later on the Lusitania in 1915, heroically giving his life-jacket to a female passenger as the ship sank even though he could not swim; there’s a memorial to him on the A24 outside Dorking. He was succeeded by Reginald Claypoole Vanderbilt, another equestrian, who died in his forties from liver failure caused by alcohol abuse.

But the Vanderbilt train hadn’t hit the buffers yet. Far from it.

Gloria Vanderbilt Cooper with lover Frank Sinatra and his son Frank Jr. Image by Everett/REX/Shutterstock

In fact the last Vanderbilt to sit on the board of the New York Central Railway was Harold Stirling Vanderbilt (three-times winner of the America’s Cup yacht race and an inventor of Contract Bridge), the great-grandson of the Commodore. He picked up the reins from his motor-mad older brother William K Vanderbilt II, whose son and heir had died in a car crash in 1933. Harold ran the business until a hostile takeover in 1954 took it from family hands.

‘That’s one of the misconceptions about the Vanderbilts,’ says Michael McGerr, a professor of history at Indiana University and author of a forthcoming biography of the Vanderbilt family. ‘The Vanderbilts really didn’t fail in business. They failed as a family.’

On one hand, they ran low on boys.

Also the pressure started to get to them: ‘A good number of the Vanderbilts weren’t very happy – the males especially,’ adds McGerr. ‘The difficulty in becoming an American aristocrat is you have to keep proving that you’re aristocratic and you’re a dominant business figure. Not all of them were up to it.’

Then there were the divorces. Both Cornelius II and his brother William divorced (Alva got the Marble House). But they were tame compared to their successors: Cornelius’s grandson, Cornelius Vanderbilt IV, married seven times and his first cousin, the fashion designer and writer Gloria Vanderbilt Cooper – perhaps most famous for line of designer jeans – has had four husbands, not to mention flings with the likes of Marlon Brando, Frank Sinatra and Roald Dahl. ‘People were shocked by it,’ adds McGerr. ‘Divorce was called the Vanderbilt curse.’

Indeed Gloria, whose son is CNN anchor Anderson Cooper, was also the subject of a scandalous legal battle in 1934 when her paternal aunt, Gertrude, fought her mother – also named Gloria – for custody of her niece, who was at nine was already an heiress. The case of the ‘poor little rich girl’ made headlines around the world.

And let’s not forget Consuelo, who was finally divorced from the Duke of Marlborough in 1921 (after providing – as she put it – ‘an heir and a spare’). She had asked the Papacy to annul the marriage on the grounds of coercion. That stunk to high heaven.

‘If you’re an aristrocrat, your family is supposed to be better than others,’ says McGerr, who says they lost status as a result. ‘They were notably dysfunctional and they failed as a family because survivors one way or the other rejected the common obsession.’

In short, just like the railways they managed, they ran out of puff.

So what’s left of their legacy?

Gilda Vanderbilt in 1959

The Commodore is still revered for his business acumen and as someone who, according to TJ Stiles, ‘helped to create competitiveness as a lasting American economic virtue’. One irony is that while he fashioned the American Dream, he also undermined it: ‘By helping to create the truly large business corporation,’ says Stiles, ‘Vanderbilt created a world in which the path formed for most Americans would be as wage earners for a large institution. What he did would become harder because of what he did.’ His successors, variously, helped define the ‘nothing succeeds likes excess’ mentality of the Gilded Age – the flowering of a new American plutocracy at the end of the 19th and start of the 20th century.

In physical terms, there’s Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, endowed with $1 million by the Commodore in 1873, and regarded by many as the greatest single legacy of the family. Harold Stirling Vanderbilt endowed it further and served on its board in the 1960s. There are also the houses, many of which are museums, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, which was founded in 1930 by the artist Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, daughter of Cornelius II, with 500 works from her own collection. In May 2015, this moved to a much larger $422-million home designed by the architect of London’s Shard, Renzo Piano. Several of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s descendants sit on its board and the futuristic new home commands sweeping views of the Hudson River. Appropriately enough, since that’s where the Vanderbilt story began.

This article is taken from our January/February issue. Subscribe here.

Main image: Getty